In Good Hands: archiving correctly

Good preservation allows films to survive the test of time decades after their original release. Miguel Gonzalez reports on the challenges of preserving the country’s audiovisual history.

Good preservation allows films to survive the test of time decades after their original release. Miguel Gonzalez reports on the challenges of preserving the country’s audiovisual history.

Human lifespan and collective memory are both so short that it’s no surprise many films are condemned to disappear from the face of the Earth, completely forgotten by its audience. But when the work is being archived and preserved properly, there’s always the possibility of a second chance. Take, for example, the work of Giorgio Mangiamele.

‘Giorgio who?’ Many may ask.

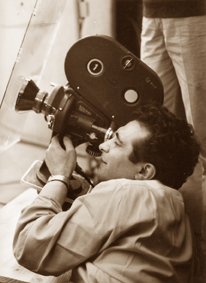

Italian-born Mangiamele made his first feature Il Contratto in Melbourne in 1953. A pioneer, he was the first to document the experience of migrants in post-war Australia, and was one of the few art cinema directors working in the industry in the difficult decades of 1950 and 1960. Although his feature Clay was the first Australian film to screen at Cannes to critical acclaim, his work never had a huge impact at the box office. Fifty years later, the story sounds eerily familiar.

However, the late Mangiamele’s work is back and ready to find a new, more appreciative audience, thanks to the efforts of the National Film and Sound Archive.

The NFSA has restored four of Mangiamele’s films (Il Contratto, Ninety Nine Per Cent, Clay and The Spag). One of the main challenges was the sound, because Mangiamele used to shoot without recording any sound, opting to add the soundtrack later. It was decided that Il Contratto, with its confusing and unfinished soundtrack available on the original release prints, would be treated as a silent film. For the other titles, the audio presented problems with synchronisation, due to Mangiamele’s limited technical resources, as well as the hiss, clicks and pops that can be expected from a film’s natural ageing process.

As part of the restoration work, the optical sound negative was transferred to digital using Chace COSP Xi technology, to optimise playback from the analogue source. Synchronisation issues were addressed using Nuendo software, and the sound was cleaned up using work station CUBEtec plug-ins. New sound negatives were created, processed and further synchronised on a film editing machine with newly created picture duplicate negatives.

In the 16mm Il Contratto, some shots were underexposed (resulting in unintended graininess) and edited together with well-lit ones, so the films had to be graded to compensate for camera exposure changes. Lucky for the laboratory technicians, the problem was not as noticeable in Ninety Nine Per Cent and Clay, which were shot a decade later on 35mm film stock capable of a broader exposure range.

The NFSA aims to hold several copies of a film, for preservation (not to be used for anything), duping (used to make new prints or transfers) and access/distribution prints. The latter were screened at this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival, and the resulting work is available on DVD through Ronin Films.

The digital dilemma

While Mangiamele’s works have been given a rare second life, not every film in the NFSA collection can receive the same treatment. Holding more than 200,000 Australian films in its vaults, the NFSA must prioritise its preservation work, focusing on films which are unique and not held elsewhere, in physical

danger of disintegration, or can illustrate important elements of the history of national cinema. Ideally, a film must meet all the criteria to be at the top of the very long list.

Deciding what films should be a priority is only one of the many dilemmas the NFSA must resolve. While film archives around the world have developed preservation techniques that would allow – at least in theory – their collections to last for 400 years in controlled conditions, the growth of digital cinema is changing everything. In less than a decade, few cinemas will be able to project film. How will an archive screen its prints in the future? Why don’t they just digitise everything?

NFSA Development Manager Executive and former Atlab legend, Dominic Case, believes the answer is not as straightforward as it might seem.

“Our program is to develop, preserve and present Australia’s National Collection, and make it available to all Australians. Not just now, but forever, so we must ensure that the collection is accessible in the future. Archivists are not the dusty historians that you might think; we must be futurists too,” said Case. “There really isn’t any alternative but to start acquiring or making Digital Cinema Prints for our screening collection.

It’s not an insignificant task, and of course there are issues specific to this application. For current material we need to resolve protocols about encryption. For older material, it’s a big cost to digitise for just one or two copies.”

There are three main issues to resolve before digital preservation becomes the norm. The first is storage size, because the Archive must preserve at the highest quality, without compression. A digital version containing all the data in an original 35mm negative would take over 50 Megabytes per frame, or 10-20 Terabytes for a full feature. All preservation copies in the NFSA collection would require between 80 and 120 Petabytes.

The second variable is recoverability; at this point in time, no-one knows yet how long or how reliably digital data can be preserved. While we can expect analogue materials to decay over time, with digital data there are only two options: it’s either recoverable or it isn’t.

“Do we trust the technology? All you need to see a film image is a light source. Once the equipment to retrieve a digital image is lost, the image itself is lost too,” said Case. “It is possible to restore even severely faded colour film images via a digital intermediate stage. Digital loss is much more abrupt, unpredictable, and devastating when it happens.”

The third problem is the never-ending availability of new formats – LTO 1 to 6: MPEG 1 to 4 and so on – that make it almost impossible to choose from.

“Preserving on film is the most consistent option with archival philosophies, and appears to be the best prospect for long-term preservation. In a very few years, digital will certainly become cheaper, probably more secure in the long term, and we may resolve the philosophical issues. Film, on the other hand, will become harder to get and to use.

So the best plan seems to be to keep the chillers going, and continue making new preservation copies on film, until those things happen,” explained Case. “But there is many years’ work, whichever technology is used. Even if we could switch to a low-cost, low maintenance, secure digital solution tomorrow, we’d still need our film collection to last for 100 years, because it would take that long to transfer everything onto it.”

What about the leftovers

In addition to long-term preservation issues, the NFSA is also working on building a closer relationship with the audiovisual production community, where many producers and directors don’t necessarily see the value in archiving their work.

“Filmmakers must understand that, if they approach the NFSA, their film survives ideally in its best reproducible form, and remains accessible to them,” said Senior Film Curator Meg Labrum. “When they finish a project, filmmakers move on to the next thing and can’t be bothered with everything that’s left behind, the ‘leftovers’. But if we’ve got the material here, five, ten, twenty years down the trail, they can do something new with it. For example, Jane Campion and Jan Chapman are very interested in DCPs for The Piano, and because we’ve preserved the material, the result is a new analogue version of the film that can be used towards digital screening materials that look as beautiful as the original.”

All Screen Australia-funded features and television programs must deliver a mint print from the lab, the digital intermediate files, the master soundtrack files and/or other items, depending on the format on which the project has been completed. Beyond those obligations, Labrum encourages producers and directors to approach the NFSA to discuss their options.

“Many producers are worried about the loss of possible commercial interest down the trail,” said Labrum, “and they get very tense if it’s their only copy or the masters. There’s always a negotiation stage where we sort the rights out; they don’t have to let go of their ownership.”

“What’s in it for filmmakers,” added Labrum, “if they archive their materials? Future recognition and a continued life for their work; the NFSA is in the business of reconnecting our audiovisual heritage with the Australian public. And remember, you don’t have to be dead to be archived.”

I keep all my films on an external hard drive. But films that are made with no budget in a situation where you’re reduced to a hobbyist? I doubt anyone will care…my films will probably end up in the bin some day when I die.

User ID not verified.

It should be remarked that author Gonzalez is a staffer with NFSA. His story does not say where the Mangiamele films have been over all this period. Since CLAY, at least, was AFI-awarded, this film maker has not been unknown.

Representation within NFSA of films that won AFI awards, let alone were nominated, is patchy and lessening over the years since 1980.

User ID not verified.