The newer the medium, the worse the media bullshit

Last week Sir Martin Sorrell pointed out that Facebook’s claims about video views lack credibility. The issue is just the latest evidence that digital media is driving a transparency crisis, argues Mumbrella’s Tim Burrowes.

Last week Sir Martin Sorrell pointed out that Facebook’s claims about video views lack credibility. The issue is just the latest evidence that digital media is driving a transparency crisis, argues Mumbrella’s Tim Burrowes.

I had an eye-opening chat to a blogger the other day.

For the sake of argument, we’ll call her Penelope.

Having established her “influencer” credentials by building up a following in her particular Instagram niche, she had been urged by the agency representing her that it was time to launch a website.

This agency (to protect the innocent, I should point out that most people won’t have heard of them) had advised Penelope the best way of getting more dollars from clients was to have a web presence too.

So Penelope went ahead and built a blog, and the agency designed her a media kit.

In that kit, she was surprised to read that her yet-to-launch offering apparently had more unique visits per month that many mainstream news sites.

Penelope asked her agency about the outlandish claim. It was normal in a media kit to take an optimistic guess at what the site might one day achieve in traffic, she was reassured.

But what if a client asked for proof, Penelope wanted to know? “That’s what Google Analytics and Photoshop are for,” the agency replied.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the same goes for all of the influencers on the agency’s books.

But guess what? In all the times brands have paid Penelope to post images of their clothes, snacks and luxury destinations, nobody has ever asked her to prove her audience.

Perhaps it’s not a surprise, given that the influencer space is the fastest developing business opportunity in marketing at present. If you thought the world went nuts about content marketing last year, then that’s nothing compared to the influencer gold rush occurring right now. This is an industry which loves to be first into the next big thing, often at the expense of knowing, or even measuring, what the return on investment looks like.

That’s why we’re seeing so many would-be influencers cheaply buying fake followers and likes to look more credible in advertiser eyes.

It was most amusing when many of them lost huge chunks of their followings overnight when Instagram held its great cleanup late last year. (I wonder how many brands then asked influencers for money back. Mind you, most people’s numbers have crept back up again since, so it may be time for another cull.)

But it’s not just the influencer space where the media bullshit abounds. And the further we go from traditional media, the less we can automatically trust the numbers.

Sorrell: Facebook video claims are “ludicrous”

As WPP boss Sir Martin Sorrell rightly pointed out on Friday, social video claims – and particularly those being made by Facebook right now mean almost nothing.

You’ll have seen those videos go past in your Facebook feed. Muted as you scrolled past, if it played for three seconds, Facebook is still counting you as a viewer, even if you remain unaware it existed.

You’d be foolish to automatically switch your strategy from YouTube to Facebook on the back of these dodgy stats, yet many brands are doing just that. (To be clear, I’m not arguing against posting native video to each major platform. That makes sense, just don’t do it because you think the number means something – and certainly don’t incentivise your agency on it.)

Then of course comes the huge problem of online ad fraud. Brands can reasonably assume that a large percentage (5%? 10%? 20%? Who knows…) of clicks on their ads are fraudulent, particularly when bought through ad networks. There’s no human, just a program doing that clicking.

Given that media agencies are all now in the programmatic business, their interests are no longer necessarily aligned with those of their clients when it comes to detecting dodgy clicks. Not to mention of course, the reduction in transparency for clients when agencies indulge in the profit-friendly arbitrage model in their programmatic offerings.

The Interactive Advertising Bureau, funded by Australia’s digital media companies, promised to commission a study into ad fraud back in February. I wonder how that’s going.

At least traditional media has had a chance for trustworthy methodologies to emerge over the years, even if the industry doesn’t always give them the weight they deserve.

This is one reason why I’m so fond of circulation audits for newspapers and magazines (and indeed, websites and email newsletters).

If I’m spending a brand’s money, first of all I’d like to know if the publisher can prove that the number of copies they claim to have printed, really were printed.

Given the relatively low cost of auditing I always find it hard to think of a reasonable explanation for a publication not to audit, other than the number being embarrassingly low.

Bauer Media withdrew Zoo Weekly from the audit after its circulation number declined to 24,122. If the rate of decline continued at the same pace, it will now be well below 20,000. Instead, the unsophisticated media buyer can make their spending choice on the Zoo Weekly media kit page, which claims an impressive readership of 138,000, via the Roy Morgan Readership survey. This methodology relies on asking people what they recall reading over the past week.

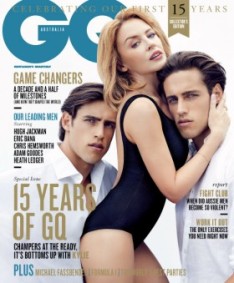

GQ: Circulation below 10,000?

Similarly, I’d always wondered what NewsLifeMedia’s GQ really did in circulation terms, as it wasn’t audited. The current claimed GQ readership number, vis the EMMA industry-funded survey, is 123,000.

Yet it took last year’s stunning leak of News Corp’s internal accounts, published by Crikey, to reveal that even back in 2013, GQ was selling only 14,000 copies – something I’m not aware of it ever having admitted publicly. Two years on, if GQ has followed most mags’ pattern of circulation decline, that would be well below 10,000.

Yet my impression is that media agencies do not ask publishers enough hard questions about why they are not audited.

By the way, I have a dog in this race: Unlike Mumbrella, our rivals B&T and AdNews do not audit their digital properties.

It’s a constant cause of puzzlement that relatively sophisticated media brands don’t ask tougher questions about why somebody wouldn’t spend those few dollars on auditing to prove audience claims if they’re true.

But when it comes to the future of print circulation audits, I must admit I’m a pessimist. I fear that there are too many aligned interests among publishers who would prefer that the industry standard to become estimated readership, not audit. I’m not sure how much longer the Audited Media Association of Australia will survive, unless media agencies and brands really demand it in order to keep the media owners honest.

Readership is a great planning tool and a lousy fraud deterrent.

But if you were a publisher experiencing quarter after quarter of decline, it’s easy to understand why paying to publicise that bad news is unattractive, unless it’s the cost of being in the game. Increasingly, it’s not.

Another traditional medium that has found a more effective, and subtle, form of misdirection is radio.

Next time the radio numbers come out in just under a fortnight, just watch how they get reported in the press.

Everybody will report audience share, and nobody (Mumbrella included, I’m afraid) will report actual audience numbers.

Which is helpful to the radio industry, because the share number sounds impressive (based as it is only on people listening to radio at the time, not the whole population) while the reach number is so much smaller than many would think.

So the radio industry simply holds back those reach numbers from the press, and share remains the currency, unsatisfactory as it is. The reach numbers stay internal to the stations.

At least most people see OzTAM’s TV numbers as a credible best estimate. But clients should still look out for traps. Mediacom’s scandal came because when the OzTAM numbers didn’t reach the campaign targets, staff retrospectively forged those targets when reporting back to clients.

As an industry, we can’t be trusted to mark our own homework.

In Cold War anti nuclear proliferation negotiations, the key phrase was “Trust, but verify”.

The combination of inexperienced and busy marketers, conflicted agencies and incentivised media owners is creating a situation of unprecedented media bullshit.

There’s way too much trust and way too little verification.

Tim Burrowes is Mumbrella’s content director

- (5.30pm update: A few hours after this post was published, Bauer Media announced the closure of Zoo.)

Linkedin

Linkedin

Too many brands have got influencer influenza.

I’m absolutely amazed that a number of the blogger and influencer agencies are still pushing Instagram posts by talent when its blantently clear there’s little merit to using them and the ROI is minimal. Let me explain why –

– if you start looking at many of the 50-100k people, their followers are often wel above 50% foreign. Few brands have the desire to spend local marketing dollars reaching global audiences.

– audience demographics, particularly male followers . If your influencer is one of the many women who spend their life wearing little and photographing your product alongside their bodies and you think you’ve got amazing reach…. Check out how many of those followers are male. Probably not the best spend for your fem beauty product.

– no view metrics. There’s absolutely no understanding of whether your 9am post got seen by anyone.

– What Caption – no one reads Instagram captions. You can’t click a URL and enagagement around promos through workarounds like ‘click the link in my profile or tag your friends’ convert very little when you consider the likes. People don’t read Instagram, it’s a visual platform.

– fake followers. Need I say more.

Instagram – from an influencer perspective – is a black hole for ROI and investment accountability. I’d love to hear a brand come out and demonstrate its Instagram success. Mostly I just hear from blogger agencies and influencers… Instagram ads on the other hand… Go for it.

User ID not verified.

Tim,

Good article as usual. And a good complement to all the posts about ad blocking in recent weeks.

I find it somewhat ironic but unsurprising that the most measurable of media, digital, is already facing its own crisis of measurement confidence. The issue in all of this, whether traditional media or new is that the advocates of both sides still seem to be in love with measuring themselves. Not their effect. Reach, frequency, views, likes, clicks. They are all the same to me. Eyeballs, three seconds or thirty, however they are measured is merely a measure of ‘did we execute OK’? Not did we do any good? Important – for sure, often overlooked indeed, but the right end measure? I personally think not.

Maybe, media owners (old and new) should start taking the notion of measuring their effect on brand and consumer behaviour much more seriously, rather than just the comparing the size of their increasingly flaccid and disinterested audience. Otherwise they will risk appearing like they are just trying to flog whatever dead horse they are currently selling. My hope is that the analytical capabilities present inside the Googles and Facebooks of this world will allow them to move their focus here in time. My faith in the FTA channels to so the same given the pressures they are under is somewhat less.

User ID not verified.

Evaluate effectiveness by something real … like campaign results. Digital is much easier than traditional to quantify when brands work out what it is they should actually measure.

User ID not verified.

to Influencer Influenza (comment #1), if you’re looking for Instagram success stories, check out Frank Body body scrubs. The founders attribute much of their ‘overnight’ success ($20million in 18 months) to their instagram account – it’s a great example of social media done right.

User ID not verified.

A simple idea: All bloggers should allow media buyers, clients and agencies access to their Google Analytics in a “read only” capacity, covering stats relating to Unique Browsers, Acquisition and basic tech / demo.

Another short cut, a very rough rule of thumb. Take the number of shares / likes / comments and divide that number by 0.07 for view numbers.

e.g.: 50 likes / 0.07 = Approx 714 viewers. It’s a rule of thumb, but generally pretty accurate across all categories, channels and formats.

User ID not verified.

Con: agreed.

Jess: a great case study. So many businesses have turned big, overnight, via social.

People with agendas distort facts. They are the old school, fat, 3rd parties, watching their revenues crumble.

User ID not verified.

P.s.. Cowboy agencies spruiking inflated analytics can naff off too.

User ID not verified.

Fascinating story. Thank you.

User ID not verified.

That story about “Penelope” is fucking appalling Tim.

I’m sorry for swearing but hearing about practices like this that make my blood boil. It detracts from all those who are doing a great job with integrity in the influencer space.

I would recommend that all brands and agencies ask influencers for screenshots of their Google Analytics, Facebook Insights and YouTube Analytics – they should be more than happy to share them, and if they’re not then reconsider investing your spend with them.

User ID not verified.

That story about “Penelope” is f*cking appalling Tim. Hearing about practices like this make my blood boil. It detracts from all those who are doing a great job with integrity in the influencer space.

I would recommend that all brands and agencies ask influencers for screenshots of their Google Analytics, Facebook Insights and YouTube Analytics – they should be more than happy to share them, and if they’re not then reconsider investing your spend with them

User ID not verified.

The elephant in the room – most instagram ‘followers’ are bought.

You can even buy followers who will comment, in broken english, how beautiful you look, what a big fan they are, etc.

It’s so easy to do on that platform, as a user’s followers are hidden.

And still the marketing companies fall for it, and send free product etc to the so-called ‘influencer’.

User ID not verified.

Timely story. This week in UK the Public Relations Consultants Association (PRCA) revealed the findings of its Digital PR Report 2015. One key finding was the growth in blogger outreach for both in-house and agency PR practitioners.

In-house investment in influencer (e.g. blogger) outreach/engagement has seen growth of 11% over the past two years – from 41% in 2013, to 50% in 2014, and to 52% in 2015.

User ID not verified.

Take The Plant Hunter as an example.

Here is the advertise page: http://theplanthunter.com.au/advertise/ It does not site exact views / user metrics, however does state: ‘Having only launched in November 2013, we’ve already been described as Australia’s best online magazine’. I would call it a ‘website’?

Similarweb says $5k visits:

http://www.similarweb.com/webs.....ter.com.au

Actual unique users will be lower than that. For Australia’s ‘best online magazine’, I am wondering why the visits are so low?

My point?

More fool clients who do not subscribe to a variety of web analytic’s tools themselves in order to understand how many visits third party sites receive. Agencies also.

Experian

Neilson

GA

Similarweb

etc

User ID not verified.

Tim, great article.

The only surprising thing to me is that so many people are surprised.

No audience measurement is perfect. What we’re after is “acceptable estimates” of the audience.

Note the word “audience”. Not traffic. Not copies sold. Not plays or stream starts. We need the people count of audience. Sure there are correlations (some strong, some poor) in these other metrics but they are at best a cohort. We can use them in hybrid systems but standing alone they are insufficient.

And as you point out, the ‘traditional media” tend to do this better than the “new media” IMHO a lot of this was the “new media” falling in love with “the big number” (didn’t matter that it carried little meaning or commercial relevance) in the initial launch and growth phase, and a lot simply can’t shake the habit 10-15 years later.

A wise person (often attributed to Einstein) once said “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”. That applies perfectly to the Internet. Again IMHO, it is the most countable medium but over the years has been one of the least accountable for the reasons you point out in your article. Having said that, things are changing and the swing to people-based measurement that is accountable to marketing and brand-building is happening (and boy is it hard to do).

Anyway, I’d better stop banging on, or you’ll need to buy more disk space!

Cheers.

User ID not verified.

“As an industry, we can’t be trusted to mark our own homework.”

The fact that marketing managers are still signing up for such bunkum in the search for a silver bullet is exactly why marketing has become less influential and increasingly sidelined in many businesses – moved to the back of the class to play with the social media equivalents of safety scissors and glitter, while the rest of the team gets on with running the business.

According to The Fournaise Group (yes, they’re a marketing analytics agency so the irony isn’t lost), 80% of CEOs don’t trust the work or advice of their marketing teams, while 90% of the same CEOs trust the work and advice of CFOs and CIOs.

I’m horrified by the examples in this article, but I can’t say I’m surprised.

User ID not verified.