Adland has a lot to learn from street art, in the form of ‘brandalism’

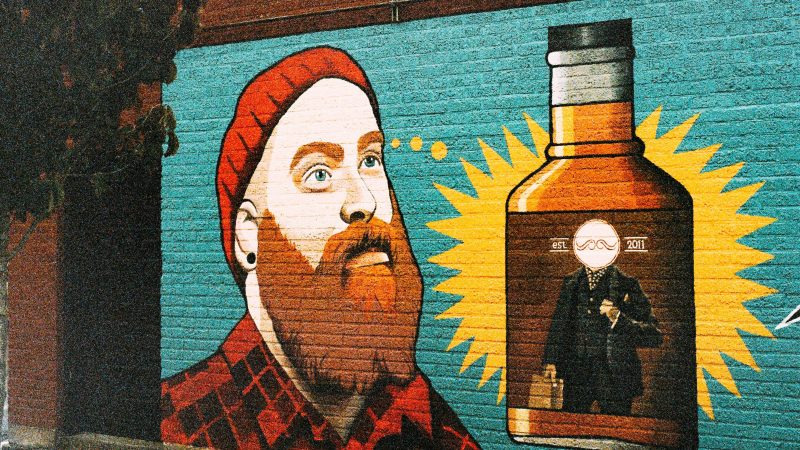

Commercial litter with “wafer-thin creative appeal” is everywhere, argues Tijan Biner. Instead, brands and agencies should ensure ads become art in the form of ‘brandalism’.

The appeal of urban street art is thriving. Seen by some conservatives as merely an underground reflection of adolescent rebellion, street art is starting to be recognised as much more than just vandalism. It is powerful and culturally valuable, giving us all a captivating reason to look up in an era where we’re so used to looking down.

Now before I continue, it’s important to note that the difference between street art and vandalism lies in intention. Tagging – the act of scrawling a crude image or nickname with spray paint or markers – is akin to a dog marking its territory. It’s a self-interested, and sometimes slanderous and threatening, form of self-expression. Just a quick glimpse outside the train window on my commute shows walls thick with layers upon layers of senseless scribbles.

On the flip side, I’m sick to death of the commercial, visual litter too. Good on outdoor media. As the antidote (and bed partner) to digital, they have taken advantage (I’d do the same), but now we’re bombarded by outdoor media with wafer-thin creative appeal. Marketers have myriad of choices when it comes to connecting with consumers, and death by volume is not the answer. I would rather see someone’s artistic expression painted on our city walls over a tacky billboard any day. Authentic street art inspires interpretation and commentary. It’s the evolution of a concept, brought to life by a passionately creative artist.

“…participants wore eye-tracking glasses and had devices attached to their hands to track what they were looking at.”

I guess that would work if the participant was Emily Eyefinger.

When an artisitc movement becomes co-opted by marketing, it becomes irrelevant. Branded Street art may provide a momentary bounce of sales (which I guess is the idea until marketing moves onto the next beautiful thing to destroy) but long term will simply train the public to ignore public art.

The very final line is all you need to know. The author works in advertising. And happens to know almost nothing about art.

Interesting, but once again a public media site writes about things they don’t know much about.

Case in point – once again the old and tired “tagging is senseless scribble” garbage. Have you ever actually taken the time to really look at a tag? Something that an artist may take decades to perfect and get right. Usually minimal likes done fluidly and quickly,it is on par in technique and mastery as much as a piece 9g Chinese and Japanese calligraphy – and just because you haven’t taken the time to really look at it and study itzot decipher it doesn’t mean it is not as legitimate an artwork as every other work of art. Like all art, some is good, some if bad habit it is still set, not just “mindl3ss scribble”

Brandalism sucks, but it’s hard to take an article about it seriously when the writer negates her credibility on talking about the whole thing in the first few paragraphs.

Can’t wait to start seeing writers doing panels for brands. Only steel is real.

To criticise tagging on the one hand and then applaud ‘street art’ completely negates the history of street art, which wouldn’t have existed without it.

Tagging and ‘throwies are how street artists learned the craft, and their handstyles were often built into larger pieces. Sorry to admit it, but the best ‘street artists’ grew up tagging, vandalising and doing all sorts of illegal things. It might be uncomfortable to admit, but it’s the truth.

The majority of street artists detest its commercialisation, so let’s at least acknowledge that before blindly recommending marketers jump on the bandwagon and destroying something authentic.

What artist wants their work sullied with an advertising message? Illustrators do that job. Why not just get brands to sponsor the work?…this street art bought to you by Coke. Like teams are sponsored in sport. .