Criticising the critics

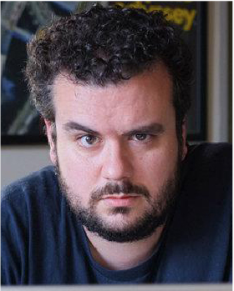

In a piece that first appeared in Encore, Lee Zachariah says that critics and film-makers both have a job to do and like it or not, they need to coexist.

In a piece that first appeared in Encore, Lee Zachariah says that critics and film-makers both have a job to do and like it or not, they need to coexist.

When author Alain de Botton decided to tear apart a reviewer the way the reviewer had torn apart de Botton’s latest book, he was breaking an unspoken rule between artist and critic.

“I will hate you ’til the day I die and wish you nothing but ill will in every career move you make. I will be watching with interest and schadenfreude,” de Botton posted on the critic’s website.

It’s always been a fragile relationship and it’s fair to say some people respond to negative criticism better than others.

I’ve worked in journalism for 15 years and I can’t think of one person I know still left in the industry who’s now not some sort of self-appointed games/books/film reviewer. There appears this army of people salivating at scoring Games Of Thrones two-stars. It’s probably the Margaret/David affect; however, I think it’s probably piss-easy and a lazy thing to do. Watch a film, review it; it’s a helluva lot easier than writing a well-researched feature and interviewing people. And you certainly don’t need a degree from an expensive media university to get into the business either.

Film reviews are like ar$eholes.

Everybody’s got one.

Most are full of s#!t.

@ Fillumstine… four-and-a-half stars….

I personally love Alain de botton’s books. Art is interpreted differently by different people, which is why I never pay attention to useless critic’s reviews. I just don’t understand why he would care so much as to incite so much hatred to the person.

By showing emotion, you are giving them what they want and showing that you actually care.

– Life lessons 101