Netflix, Disney, and other streamers hit with Australian content quotas

Netflix, Disney, Amazon and other streaming services will be forced to allocate a portion of their local revenue to producing Australian content, under new legislation to be introduced by the Albanese Government.

The proposed laws will mandate streaming services with more than one million Australian subscribers to invest either 10% of its total local expenditure — or 7.5% of total revenue — on new local drama, children’s, documentary, arts, or educational programs.

The legislation is part of the government’s landmark National Cultural Policy—Revive, a five-year plan announced in early 2023 with an aim to renew and revive Australia’s arts, entertainment and cultural sector.

It levels the playing field between the free-to-air broadcasters and pay TV providers — who have long been required to adhere to local content quotas — and the streaming services, who currently have no such requirements.

Streaming services operating in Australia already report their expenditure on local content and the number of Australian titles they produce to the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) – but this reporting is voluntarily.

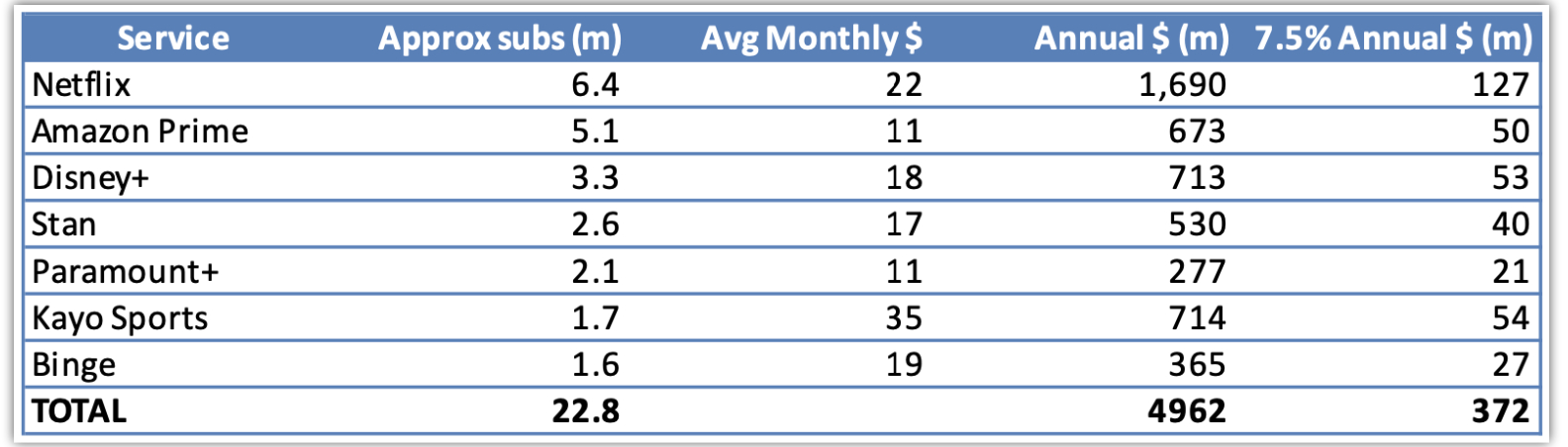

Doing some quick back-of-the-envelope calculations, Mumbrella estimates the legislation could guarantee the streamers contribute at least $372m each year to the Australian screen industry.

An estimation of Australian revenue based on subscriber numbers and mid-level subscription rates (Mumbrella)

The above table is a conservative estimate that includes subscription revenue only (no advertising), calculated by using local subscription figures from various third-party sources, and multiplying this by the cost of the middle tier available to customers. It also includes Stan, which is part of Nine (which is already subject to local content quotas).

Actual revenue numbers may differ substanially from those above: for example, Netflix reported Australian revenue of $1.3b for calendar year 2024, which would lower its quota to around $100m. We used the above method for consistency with the other streamers, where revenue is often not reported or broken out.

Netflix’s Australian expenses for 2024 were reported at $1.25 billion, of which $1.2 billion went to “distribution fees” to other companies in the Netflix Group. If this is the metric used, Netflix will be required to spend $125m annually on Australian productions.

Netflix declined to comment when contacted by Mumbrella on Wednesday morning.

It is not clear yet how the method of determining the quota — revenue or costs — will be chosen. Mumbrella has put in a query with Arts Minister Tony Burke’s office.

In announcing the legislation, Burke said in a press release: “Since their introduction in Australia, streaming services have created some extraordinary shows. This obligation will ensure that those stories – our stories – continue to be made.

“These platforms are having no problem getting their content into Australia. With this legislation we’ll be able to ensure that no matter which remote control you’re holding, Australian stories will be at your fingertips.”

Communications Minister Anika Wells added: “We want to make sure no matter which platform people are watching, Australian stories are part of their experience.”

Wells said she visited Ludo Studios, producer of international success story Bluey, and spoke with the studio’s co-founder “about the importance of locally produced content”.

“Real Australian content like Bluey matters, it connects us to who we are and shares it with the world which is why these laws are so important,” Wells said.

Like Nine, Paramount Australia straddles both worlds, operating both Network 10 and streaming service Paramount+.

A Paramount Australia spokesperson told Mumbrella it is “committed to bringing local stories to all Australians”, but stops short of giving blanket approval to the proposed quotas.

“We have proactively engaged with multiple governments over many years on how to ensure there is a sustainable pipeline of local content, across genres and formats, available to our audience,” the statement continues.

“Despite the ongoing and demonstrable commitment to our investment in local productions — as evidenced by the annual industry data we voluntarily provide to the Australian Communications and Media Authority — the government has elected to move forward with regulation.

“We look forward to reviewing the detail of the proposed local content requirement when it is available to ensure the rules that will apply to streaming services are fair, equitable and guarantee a sustainable and viable screen industry for all players.”

Seven’s chief content officer Brook Hall told Mumbrella late last month that one reason for the relative harmony recently seen between Australia’s free-to-air broadcasters is that it’s “not a level playing field” between themselves and the overseas streaming services.”

“[We have] different regulations compared to our big global titan competitors, so we’d love that level playing field,” Hall explained.

Screen Producers Australia CEO Matthew Deaner told Mumbrella the Government’s announcement was “a milestone” and “a positive outcome”, but was cautious in being too celebratory.

“We’ve got to be mindful that we need to look through the bill with a laser focus to work out any challenges we see,” Deaner told Mumbrella.

“And we know that this is not going to be everything we’d hoped for … it’s a positive outcome in that we’re at this point, because it has been a big journey across successive governments, successive ministers and many, many parliamentarians to arrive at this — given the amount of resistance that the industry and the government’s had to getting to this point.”

Some of this resistance came from Free TV, the peak body for the free-to-air stations.

Holding global streaming giants to similar production quotas as their free-to-air and pay TV counterparts may provide a windfall for Australian film and television producers. However, Free TV argued last year that the introduction of such legislation “risks creating unintended costs for local broadcasters.”

Free TV CEO Bridget Fair rallied against such legislation last October, during a remote address given at the U.S. Chapter of the International Institute of Communications in Washington, D.C.

“Free TV broadcasters spend more than any other platform on Australian content,” Fair said.

“They already face significant local content quotas and are competing against well-funded unregulated streaming platforms who don’t even pay tax. As streaming services invest heavily in high-end productions and roll out advertising tiers, commercial television broadcasters are increasingly challenged to deliver affordable, high-quality programming for Australian audiences,” she said.

Fair said the government needs to ensure any content quotas for streaming “do not artificially inflate content costs even further”. Free TV declined to comment on Tuesday’s announcement.

Many of the streamers already contribute significantly to local production.

According to the Screen Australia Drama Report 2022-23, Netflix accounted for 35% of total local drama production spending during that period. This has tripled the hours of local produced — but has also inflated costs. The average cost per hour for streaming broadcast-video-on-demand is now $3.5 million.

Despite the declarative announcement from the government, the deal is far from assured.

The government first committed to legislating local content quotas for streaming services in February 2023, earmarking a July 1, 2024 start date, but these plans were quietly delayed.

In November 2024, the ABC reported the delay was due to government concern that forcing US-owned streamers to comply with local content laws could contravene Australia’s free trade deal with the United States. The national broadcaster reported that Burke told Labor’s caucus “that the interaction of any new local content rules with the US free trade deal was a stumbling block”.

There are also various ways in which the global streamers could sidestep the intentions of this bill.

Rather than investing in “Australia’s people and their stories”, as the government press release states as the intention, Netflix could simply set one its tentpole Adam Sandler films in Melbourne, employing local production crews.

Mission Impossible II — a Paramount property — is technically classed as an Australian production, as it was largely shot in the country, using local production teams. It isn’t hard to imagine Cruise and co. returning to locations like the Opera House, Broken Hill, and Royal Randwick for the ninth installment in a $400 million blockbuster that single-handedly meets the cost requirements.

Deaner notes that “we have a very competitive landscape for those global pictures being made here” with good incentives and the infrastructure in place.

He worries that the streamers may “double count it effectively, so that the work that they would normally be doing here, they could just put under this regulatory model and therefore not have to do anything additional.”

Deaner said he would be “concerned if that was the outcome of this legislation”.

“We wanted to make sure that this regulation and this framework was particularly focused on Australian stories and defined according to the same rules that exist for other platforms that deliver Australian stories, so that there’s both a consistency of practice around that, but also opportunities for many participants in the market to be operating above the line, which is the important part of the system that creates Australian stories.

“So it’s Australian producers, Australian actors and writers and directors, they come to the table with their own narratives rather than essentially ‘below the line’: delivering on others’ intellectual property or stories from other markets or other countries.”

Deaner is optimistic in this regard, noting that “this is also a cultural reform, driven by the Minister of the Arts”.

“In terms of delivery [Burke’s] keen to see that Australians receive their own narratives and stories on these services, rather than essentially this being a way of making the programs that they would be making anyway, or that are probably more American or built for an international market.”

Nine, Disney, and Amazon did not respond to requests for comments in this story.