Dismiss AI slop at your peril

History is full of dire predictions about technology rotting our brains. The truth is usually more nuanced, writes Shaun Davies.

Slop or not: Show Runner is an AI generator where you write the story

Let’s talk about slop – the deep-faking, engagement-baiting, time-sapping, work-spoiling AI content that’s rotting our brains, destroying democracy and ripping at the fabric of reality. Or so the story goes.

As 2025 draws to a close, it feels like we’re drowning in AI-generated content. But we’re also drowning in hot takes complaining about slop. Nick Cave says it’s “a grotesque mockery of what it is to be human”. The Atlantic calls it “a tool that crushes creativity”. The Guardian says that AI slop is “destroying the internet”.

I, too, enjoy complaining about slop. I agree that a lot of it is shit. I also agree that it has the potential to cause real-world problems.

But I think it’s worth considering that all this dismissive “slop” talk that dominates media discussion of AI content is a psychological safety blanket, rationalising away the threat posed to our already-disrupted media ecosystems.

To illustrate why, let me take you on a lightning historical tour of media technologies. What did some of history’s greatest minds have to say about the emergent technologies of their times?

Writing our way to forgetfulness

Let’s start with a very important media technology called writing, which around 400BC was in the process of disrupting the established forms of communication: oratory, debate and stabbing one another. The Greek philosopher Socrates did not write books, so we only know him through the works of his student, Plato. In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates describes an Egyptian legend to make a point about the utility of writing:

“For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant.”

Doesn’t this have an echo of the current debates we have around education and workslop?

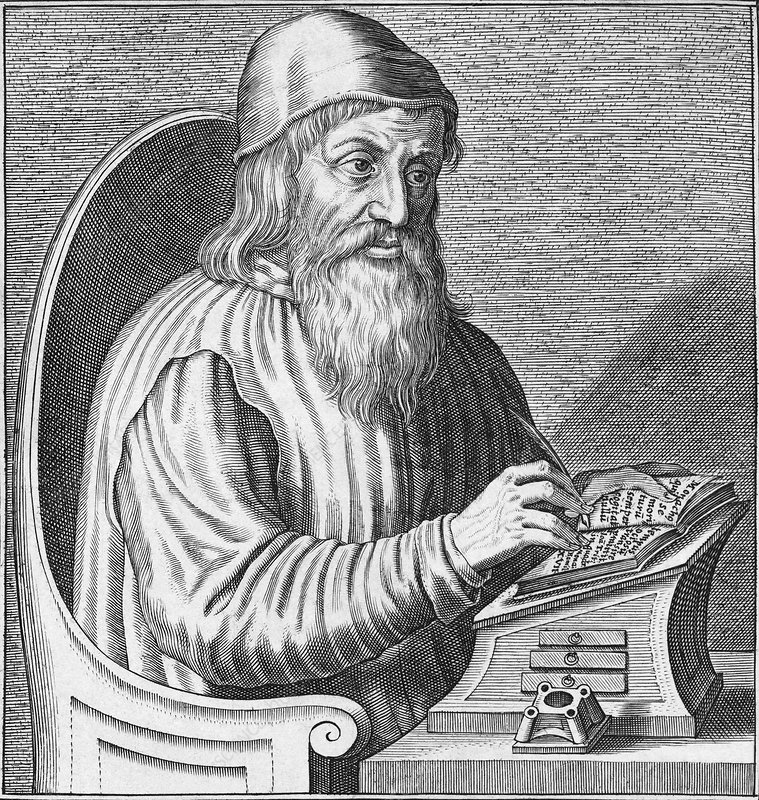

But let’s not dwell in Ancient Greece and move on to the late 1400s, when the development of the printing press “scaled up” the written word and threatened the art of scribing books by hand. The German abbott and academic Joahnnes Trithemius wrote In Defence of Scribes, which criticised printed books as poor-quality products that were “often deficient in spelling and appearance”. In contrast, scribes poured their devotion and creativity into long-lasting books on parchment.

Scribe guy: Johannes Trithemius (1462-1516), German abbot, polymath and handwriting enthusiast

Of course, Trithemius had a point. Those hand-drawn copies of the Bible and other books are stunning. Remember, too, that the printing press caused a boom in mis- and disinformation, facilitated witch burnings and destabilised the Catholic Church. But I don’t think that any of us would wish for a world without a printing press. And — fun fact — Trithemius’ own book was published via the printing press. Presumably he wanted to access scaled distribution pipelines.

Plastic verification and moral corruption

We now travel forward 400 years to the 1800s and the birth of photography. The French poet Charles Baudelaire was not the only one who thought that photography was “art’s most mortal enemy” and the refuge of “every painter too lazy to complete his studies”. The art establishment reacted with general horror to this new technology, primarily on the grounds that it was an affront to the honed skills of an artist.

Nearly 100 years later, this view remained common. In 1913 the critic Marius De Zayas said: “Photography is not Art. It is not even an art. Art is the expression of the conception of an idea. Photography is the plastic verification of a fact”.

Similarly, early cinema in the form of the Nickelodeon was dismissed by “legitimate” theatre producers as lacking artfulness. In comparison to theatre, a trip to the “flickers” was cheap and accessible to working class people and immigrants. It created a whole new market that didn’t exist before. But it was derided by the cultural gatekeepers of the time, who saw it as low-class, frivolous and even a source of moral corruption. Take this review from literary journal The New Review, it was described as “… life moving without purpose, without beauty, with no better impulse than a foolish curiosity”.

Modern media and its detractors

CNN launched in 1980 as the first 24-hour news channel

Throughout the 20th Century, the disruptions, battles and moral panics kept coming. US newspapers started a war with radio stations to limit them from broadcasting news by blocking their access to wire services, then trying to limit them to two broadcasts a day by law, but it didn’t work. Cinema operators derided television as cheap and inferior, that didn’t stop the emergence of a whole new category of media viewing.

In the 1980s, the newly launched CNN was branded “Chicken Noodle News” by critics who regarded it as a cheap and nutrition-free news slop. And they weren’t totally wrong either, as the demands of 24-hour news led journalism away from its ideal of careful verification towards a new model of speed and assertion. While CNN turned out to be quite good at a lot of things, the critique that 24-hour news would degrade information quality has been at least partially validated, as evidenced by increasing partisanship and outrage in news.

The same pattern has been sustained through more recent disruptions. In The Atlantic in 1995, the respected technology commentator Clifford Stoll wrote a notoriously wrong article, hilariously entitled: “The internet? Bah!” Here are some juicy quotes from his epic misfire — does any of it ring a bell?

An appetiser: “Lacking editors, reviewers or critics, the Internet has become a wasteland of unfiltered data. You don’t know what to ignore and what’s worth reading”.

Stoll also dismissed online shopping. “How come my local mall does more business in an afternoon than the entire Internet handles in a month?”

On human connection he said: “A network chat line is a limp substitute for meeting friends over coffee.

And perhaps most memorably: “The truth is no online database will replace your daily newspaper.”

To Stoll’s eternal credit, he later reflected on this, saying: “Now, whenever I think I know what’s happening, I temper my thoughts: Might be wrong, Cliff …”

Gently defending Stoll in a 2010 retrospective, a Newsweek columnist pointed out that the analysis wasn’t entirely without foundation: “The Internet really did suck then, and it really was a huckster’s paradise. But the fatal flaw in his argument was his assumption that it was never going to get any better.”

That is a crucial observation. Most new technologies start out low quality, and have a mix of good and bad effects. But they tend to get better. So why is each new emerging media technology met with the same claim that this time, garbage content will lead to widespread mental and moral decline?

Double disruption and bad stuff

Sloptastic: OpenAI’s Sora 2 can churn out videos in seconds

I think we’re seeing the pattern that Harvard professor Clayton Christensen spelled out in his 1997 book, The Innovator’s Dilemma. Christensen’s thesis was that established market players struggle to respond when a new entrant with a simpler, cheaper product enters the market, initially targeting underserved, less profitable segments.

Incumbents dismiss the new product as cheap or deficient, and continue to focus on their profitable and established products. This is the rational thing to do. But over time, the new offering improves, moves upmarket and eventually displaces the established leaders.

Christensen says there are two types of disruptive innovation. Low-end disruption targets over-served customers in an existing market with something that is simpler, cheaper and more convenient. New market disruption creates entirely new markets and experiences. I think AI causes both types of disruption at the same time – it both makes it cheaper to create content, and opens up entirely new types of experiences.

Now, before you peg me as a hype boosting, big-AI shill, let me be clear that I do have concerns about AI content in its current form. Chief among these concerns is copyright, a hot topic in Australia. I’m sure that most Mumbrella readers were relieved to see Labor ruling out a copyright carve-out for AI model training in Australia.

Another big problem is the use of deep fakes for AI-generated propaganda (aka slopaganda) and disinformation. As the independent reviewer of Australia’s dis- and misinformation code, I have a professional interest in this end of the AI slop production pipeline. Propaganda that makes your opponents look stupid, dehumanised and unworthy of respect is nothing new, but AI is enabling this kind of content to be scaled. The Trump administration may be the most aggressive promoter of this type of content, but it’s becoming entrenched as part of political discourse. (Don’t believe the left does it? Check out this one from New Zealand.)

Then there are the AI content farms flooding social media with fascinatingly weird, but ultimately meaningless, crap. While I’m more bullish than most people on using AI in the content production process, I do not recommend that anyone start a slop farm. Even if you’re the kind of person who ignores basic human decency, it’s a short-term business model that will quickly collapse due to unlimited competition, limited user attention and ad dollars.

A more useful critique

This historical pattern of panic, dismissal and eventual (complicated) acceptance is a well-documented cycle. But any new technology almost always contains a mix of good and bad outcomes. This history teaches us that broad, deterministic claims of cognitive or cultural collapse have repeatedly proven unfounded.

However, research also validates many specific, nuanced critiques, proving there are real things to be concerned about. TV didn’t create a “nation of morons”, but its economic model has degraded information quality in specific ways. The internet didn’t make us “shallow” (as Nicholas Carr predicted in The Shallows), but studies have shown that the presence of smartphones can reduce working memory.

This brings us back to “slop”. A moral panic about how AI-generated videos are going to destroy our minds and attention spans is unlikely to be helpful. But complaints about the extension of ad-driven business models to this new type of highly engaging content are, in my view, quite valid. So is the concern that it will be hard to tell what is fake from what is real. There will be other problems, but there will also be unexpected benefits and new types of creativity unlocked by these strange new technologies.

In media and publishing, the easiest thing to do is join the chorus saying, “Of course, we would never use AI for reporting or writing stories”. It feels principled and it keeps grumpy reporters off your back. But it’s not a realistic long-term proposition. Like the internet, this technology will get better. So instead of hand-waving the threat away with the magical “slop” word, publishers need to experiment. It’s time to wade carefully into the rivers of slop and start panning for gold.

Shaun Davies is the founder of The AI Training Company and a former Microsoft product manager. Click here for for Mumbrella.