End of an era for the British red tops

In this crossposting from The Conversation, George Brock argues that the British tabloids have had their day.

In this crossposting from The Conversation, George Brock argues that the British tabloids have had their day.

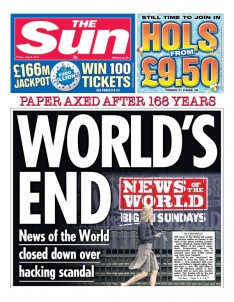

So, Andy Coulson has been found guilty of plotting to hack phones – but former colleague Rebekah Brooks walked free after the jury in the hacking trial cleared her of all criminal charges. The verdicts mark more than the end of the case which has unfolded at the Old Bailey for the past eight months. They also come at the end of an era in British popular journalism.

Not a golden age, certainly, but a distinct period during which tabloid or “red-top” journalism walked tall, looking down on more serious newspapers and their scruples. For the past half century, the mass-selling papers with red mastheads (or logos) had defied the logic of media history and swaggered at the centre of the stage.

That they reached this position at all was something of a miracle achieved against logic and the odds. The coming of television in the 1950s changed the landscape of news media, but not in the way that most predictions expected. Newspapers were not put out of business by television news, just as they had not been abolished by radio in the 1920s. But all the same, broadcasting undermined the foundations on which popular print journalism had been built.

If Rebekah was Andy’s boss and Rupert was Rebekah’s boss and…………

Rebekah was a responsible boss of a publishing business and her boss, Rupert, was renowned for his hands on, head in the data approach and………………………

Then how on earth were cheques / payments (made out to hush the victims of hacking) not picked up and questioned by Rebekah and Rupert who, it would certainly seem, had total understanding of the numbers / p&l…….and therefore would surely question a load of $10k and upward payments to randoms.

I just do not understand how this adds up with just Coulson getting a slap on the wrist and Rebekah walking free. Makes no sense at all, unless the bosses over at News do not look at their P&L’s?????