The un-negotiated contract: Why the fight for access to data and information has never mattered more

The media model has been rewritten in the past decade, but Chris Stephenson asks should the industry do more to make sure the consumer is on board with it.

At some point in the last decade a long-established contract between people, media and brands fundamentally changed. What is gradually and incrementally replacing it is an un-negotiated contract – in which information is the new currency, insights and utility are the new value, and the fight for the control of data -whether you realise it or not – is one in which you are already engaged.

The nature of the contract we’re currently negotiating will have huge implications for consumers, brands, media businesses and governments. Whether its the strategies employed by brands, the deals made in market, or the data that’s shared with our governments – how this emerging contract nets out will affect us all, and is already shaping the industry around us.

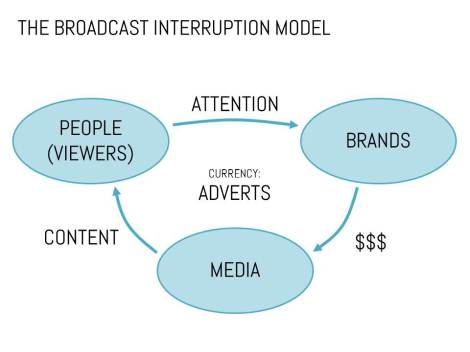

The broadcast interruption model that emerged in the 1950s was a ruthlessly effective and potent means of value exchange. Everyone involved (which was everyone) won. It was ruthlessly simple – brands gave broadcast media dollars which paid for content that people viewed, and which brands interrupted to get people’s attention.

The model was so awesome that it even accommodated channel-neutrality – it worked as well for print and radio as it did for TV, but at some point in the last decade this ruthlessly simple and effective model started to break down. Fragmentation of channels led to fragmented viewing and audiences – necessitating more investment by brands to reach the same number of people. Set-top and on-demand technologies allowed viewers to skip brand messages (although the evidence is that this was largely off-set by higher viewing in PVR households), the internet changed, well, everything … and a new generation of media businesses and brands emerged that weren’t dependent on the broadcast interruption model – or more specifically the currency that drove it.

Because what sat at the heart of that model and the old established contract – its currency – was the ad. Adverts were what media organisations sold, what brands placed and what viewers watched. They were the centre of the contract’s gravity – so much so that the very concept of advertising became synonymous and interchangeable with its most predominant vehicle … the advert.

What has tacitly emerged over the last decade has been a fundamental reworking of the relationships between the various participants in the deal – to the extent that I now think we’re working with something that looks more like this:

The emergence of new media businesses built on data – rather than broadcast ad interruption – is one of the key drivers of this new as yet un-negotiated contract. Google, Facebook, Twitter are of course the obvious examples but so too are companies like Amazon and Ebay – they revenue-generate based on the data they accumulate, and the insight this subsequently generates for advertisers. Ads are still of course part of the equation but they are no longer the point of the model … rather information is.

Better information allows and enables brands to have better contacts and connections with people … something Will Collin discussed on Mumbrella back in October in a brilliant piece that made the case for a focus on reciprocity in how brands engage people – I’ve called it utility above but the point is the same. It’s about how data and information fuel better brand ideas – ideas that are not only increasingly necessary in our fragmented cluttered world, but which are also proven to generate disproportionate ROI versus optimisation of the channel plan.

So far so nice theory, but so what? Well, what this affords us is a framework to understand the various terms of engagement being played on in what will probably be come to be understood as the data wars. Early skirmishes and alliances in an emerging contract based not on ads, but on information.

New models are emerging between brands, media owners and agencies based on information and data rather than just ads media spend. For example this case of how Twitter data is delivering new targeting capabilities.

Ads are, of course, still in play but data and information is what the new contract is predicated upon. Expand ‘media’ in the above model to include (media) agencies and you understand why the positionings around Audience Management Platforms and audience data are so vital to those involved – its about who controls the insight (and therefore the revenues).

It’s also why brands are (1) increasingly asking why they shouldn’t retain full control and analysis of their own data and (2) why some brands are looking to cut media out all together and go direct to customers (existing or potential) based on the data and information they own. Nike have used this strategy with Fuel, whilst brands like Burberry use a hugely disproportionate amount of their own media to reach people direct. Its also why media businesses now ruthlessly collect and protect first party data, and why the sharing of that data with frememies to match the demand-scale generated by agency groups makes media owners so nervous.

But its between people and the media where the contract is perhaps most vociferously being negotiated. Between Google and the European Courts with legislation that allows people to force Google to delete their data (or at least the links to their information); Facebook’s privacy settings tidy-up was part of this negotiation, as is any site’s publication of it’s cookie and targeting policy.

The other huge players in this part of the negotiation are the telcos (and I include Apple in this bracket) – whose efforts to win the Triple Play wars were awesomely captured by Nic Christensen here last month. This is important for two reasons … first, the Telcos are emerging as some of the biggest accumulators of data – that makes them significant players in the emerging contract and secondly, like the big Bay Area media companies, the data they accumulate can be appropriated by government agencies without our explicit consent.

The fact is that it has been the emergence of this new model, and the concentration of such vast quantities of people’s data into new media businesses and telecoms companies, that has fueled US, UK and other government agencies desire and demandto acquire that data as part of their ambition to ‘master the internet’.

And yet despite all of this the contract remains un-negotiated.

The conversations and debates required to do so are fragmented and diverse, but there are huge implications for brands, agencies and media businesses depending on just how that negotiation pans-out. Who own’s people’s data? Who gets to sell or target and re-target based on that data? How aggressively should and could brands pursue collection of their own customer data? Should it be made more explicit that someone’s data is being captured for advertising or targeting purposes?

To be absolutely clear, it is my opinion that this new contract is an eminently good thing. It is the emergent data and information-based value model that has given all of us access to search, social media, online marketplaces, and a world of information, education and entertainment.

What the contract promises is awesome – but to deliver, it must first be negotiated.

Chris Stephenson is strategy director of PHD

Love the piece Chris. As you’ve highlighted the main barrier to the progression of such a model / negotiation is that of ownership of data. Who owns it, how much they are prepared to share, and at what cost owners put on it vs what others are willing to play. We have to start somewhere though exciting all the same.

Excellent article Chris, As I’ve been saying all this year, people have learnt to avoid the old “ad breaks” by either recording and zapping through, or by simply jumping onto the internet if the are watching or listening to something live. It’s also never been easier to change channels or switch stations to avoid ads. People that say the old ad breaks will be replaced by product placement are wrong, because consumers are very aware of it, and there’s only so many coke cans of pizzas you can have on set! We live in very interesting times as fragmentation continues to change the landscape, faster than you can say “Netflix” or “Spotify” The days of tribalism are over and if you don’t believe me look at the nightly TV ratings, as more and more shows fail to crack the magic million mark.

All rather obvious really, circa 2009

Great article. Love the logic of the argument.

hey @Marteau @Geoff thanks for the comments … @Richard yes I think whilst the new model has been with us for a while, its the battles and negotiations for the new currency – the data – that is being played out now in new fronts all around us, but thanks for the comment