Communicating in the age of ‘untelligence’

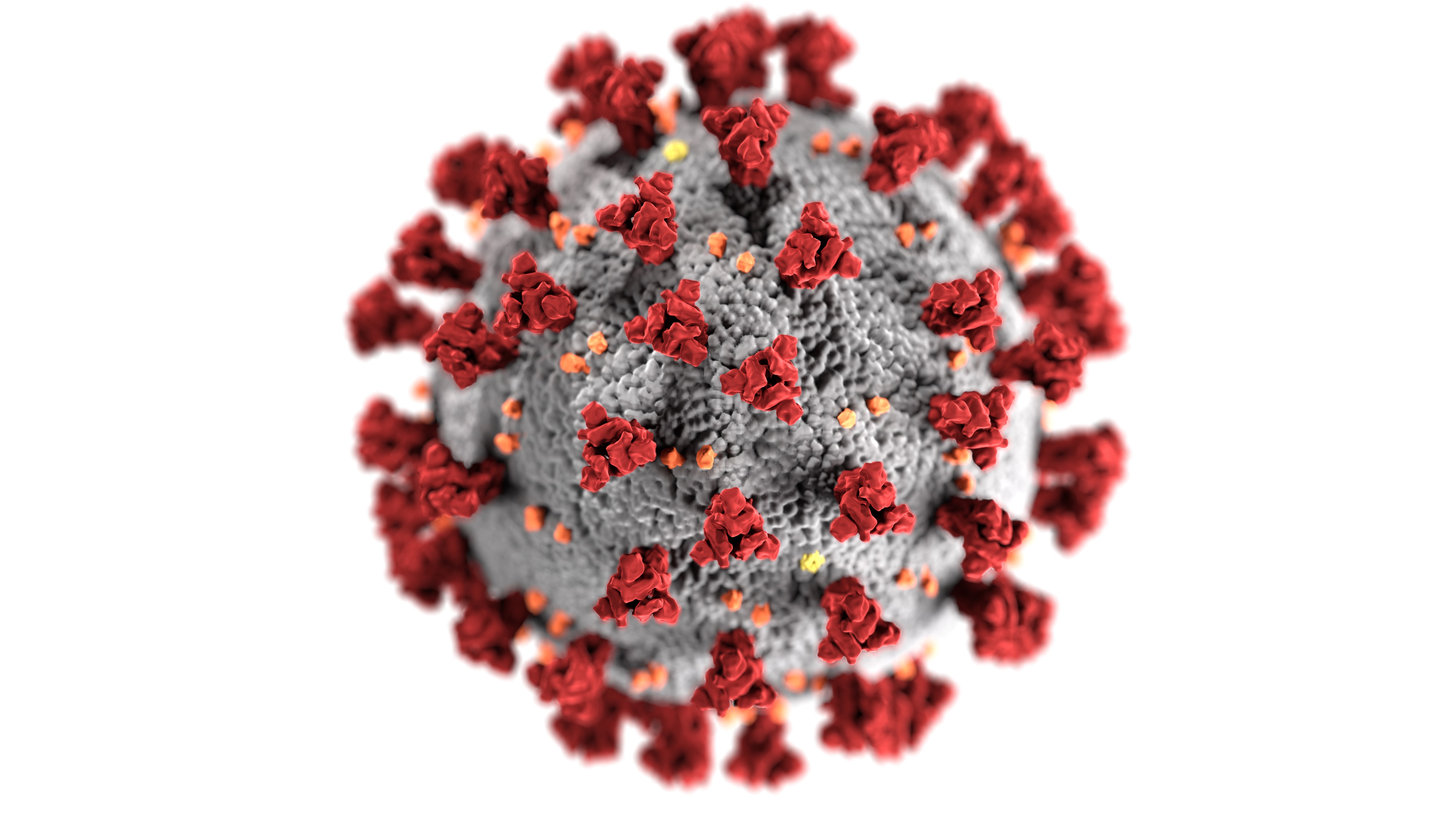

Communicating to consumers during COVID-19 is difficult enough, but when you add conspiracy theories, wayward social media posts and fear mongering to the mix, it becomes a minefield. Managing Outcomes’ Tony Jacques explores how you navigate your way through.

Issue managers and communication professionals have to deal with them every day. – people who seem to genuinely believe ideas about science and technology that are simply wrong. And social media helps spread these false beliefs at electron speed to potentially influence millions.

Look no further than the hoax claim that the coronavirus pandemic is spread by 5G wireless (it isn’t), circulated by “super-spreader celebrities” such as Woody Harrelson. And promoted by charlatans who want to sell you a $350 USB stick to protect you from infection (it won’t).