Men’s mags stand on the brink of extinction, but what they do matters

With Men’s Style finally succumbing to Bauer’s axe, Maxim and GQ are left to mount an unusual last-wicket partnership. Mumbrella’s Adam Thorn, who has worked at more than ten men’s mags in London and Sydney, analyses what’s gone wrong, and why the sector’s contribution to the industry shouldn’t be underestimated

Shortly before I resigned from the British version of men’s fashion magazine Esquire in 2015, the entire editorial team was dragged into a meeting room with our new publisher.

Good news, he said! Despite London’s publishing industry being on the brink of collapse, we’d never been more on-trend. Issues were flying off the shelves like suede sneakers! Website hits were having a moment! And advertisers were practically throwing their unstructured tweed blazers off and grappling each other for vintage double-page spreads! We were, he beamed, an example for others to follow.

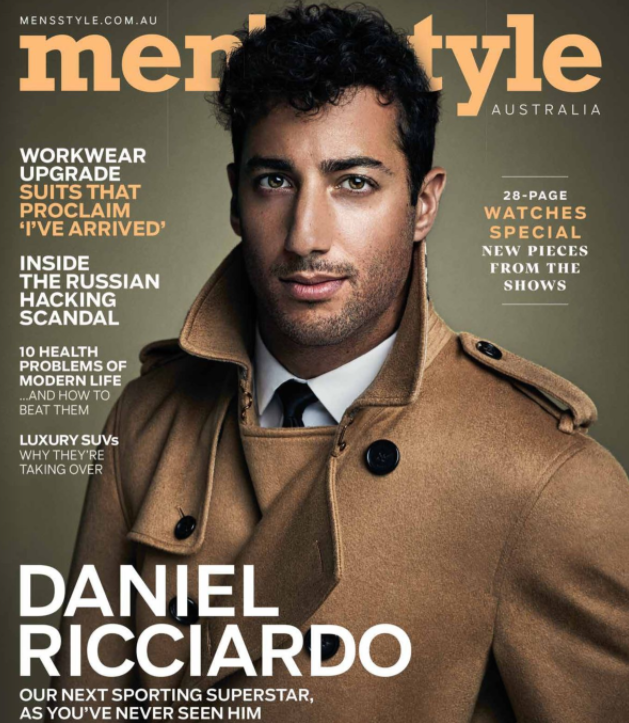

Bauer have confirmed Men’s Style Australia is closing

He’s right, I do think men need quality publications to help them navigate the world. They just won’t be printed on glossy paper

There are great sites that cater for this market and offer daily EDMs.

D’Marge is my personal favourite and is entirely local…

Excellent article Adam! But there are still some great online men’s lifestyle magazines that are burgeoning in Australia that didn’t necessarily start in print – D’marge, Executive Style, Time+Tide and our own Man of Many (https://manofmany.com) to name a few. There’s certainly still a place for the profund long-form men’s journalism you speak of.

Man of Many? 40% US readership according to SimilarWeb, less than 9% Aussie readership, this is not “burgeoning in Australia” by any stretch, it’s a clear sign of click-hungry articles with minimal appeal to Aussie readers.

Hi Cam,

As the founder of Man of Many, we’ve had huge growth in our Aussie audience (+200% in the last 12 months). Despite the lower percentages (largely due to the sheer size of the US being 12x a larger market than Australia), we remain the highest ranked men’s website on Alexa.com in Australia.

We’re also producing much more locally focused content so would welcome your feedback on what sorts of things you’d like to see or read and we’ll try integrate this more into our articles.

If you do some simple math on the SimilarWeb numbers, the estimated Aussie traffic is still higher than most of our competitors despite it only being listed as 10% of our traffic.

Cheers,

Scott

I think sometimes these publications are out of touch with the bulk of their audience. There’s a difference between aspirational and attainable. Men’s Health walks this line on a monthly basis – proclaiming to let you know how to “lose fat fast” from a male model who spends 5 hours a day at the gym.

This is bollocks. How is there no mention of Men’s Health, which has dominated men’s mags for like 20yrs or so? It may have lost some numbers in the last few years, but it was a 4x the size of the others last time I looked.

And as for blogs/influencers, I’d rather know when an ad is an ad.

Isn’t Men’s Health a fitness/health mag? The name says it all. Different readership, different advertisers.

Maybe the fact that people think mags like Men’s Health and mags like Men’s Style had vastly different readerships is part of the problem. Sales teams never worked out that people who work out and are into fitness might be really into fashion because, you know, they look good in clothes too. A lack of imagination that nobody could convince high-value advertisers to invest in the fitness market.

Men’s Health is one of the better ‘men’s lifestyle’ magazines because it has an actual base of common reader interest but expands from that to a sensible set of related topics, and it’s had the benefit of solid editors and journalists behind it.

Here’s the thing: you can’t just say you are a “men’s lifestyle” magazine or website or blog, because there is no such thing as a singular “men’s lifestyle”. You have to start with a solid foundation of a real and sufficiently broad interest – health is the best one – and then add on related content which those readers will find appealing. This is why so many “men’s lifestyle” websites and blogs have very incredibly low Australian readership but survive as vacuous grabs for advertising booked by lazy media buyers.

Even so, health-based mens’ titles are not finding life as easy these days. In the US, Men’s Fitness has been folded into its sibling Men’s Journal, and MJ is actually the better for it now, once again because this gives it a more unifying focus for content and readership.

I spent a lot of time looking at Australian men’s lifestyle blogs in the second half of 2017 and websites like D’Marge, Man of Many, EFTM, Hey Gents etc are generally pretty lazy and when you look at their traffic you can see how many are basically pulling the wool over media buyers’ eyes.

Totally agree. Men’s Health is solid. In some of these segments, it’s about being the ‘last man standing’ and owning the space like Men’s Health. This is also Rupert’s strategy of ensuring his print products are the last remaining ones.

I was all set to find out why such magazines mattered, and the answer was, an interview with an actor best known for playing a comic strip character, and the need for “a guiding hand” to be found within its pages. Well, I won’t have the benefit of the guiding hand now. But then, as so often happens, I only first heard of this august journal when its closure was announced.

Do people really want to spend all their days viewing tiny nuggets of unactionable emotion? If so, journalism is doomed.

If not, then the long form producers need to find ways into people’s phones that pays them money.

Paying $15 for a book of ads that tell you you’re a loser if you don’t have a $2,000 cardigan was never appealing for the bulk of guys; the only male targeted magazines to deliver high reach had women in bikinis on the cover.

This industry wide delusion that print is not dead needs to stop. The amazing cultural contributions listed in this article are 50 and 20 years old. Anyone born since these glory days reads this stuff on their phone.

Lets be blunt, surprised they lasted so long. A lot of these magazines existed because fashion brands and media planners kept playing along. Dodgy circulation games mean audience metrics are likely to be a crock, and ROI for campaigns very low.

Congratulations! Is there an insider at Mumbrella that can leak the sale price so you can publish it?

Congratulations and thanks for a refreshingly honest and candid article about your experience. Great stuff. And we look forward to more great news and events from Team Mumbrella.

Adam, your experience with Esquire UK is far from uncommon. There are many instances of similar circ-boosting plays in the Australian market and even worse. In the decade before it was sold to Bauer, ACP would prop up the circ of many market-leading titles by buying copies themselves and then warehousing them. The magazine’s own marketing budget would be spent purchasing ‘grace’ copies so they could be included in the circ reports and thus maintain that magazine’s market-leading position and justify its high ad rates. If you look back at the biggest circ drops of many premium ACP titles those often happened not only due to a native sales slump but mark the period when this strategy was abandoned, and pulling away those props meant an instant drop of 10k-20k for some mags!