The Biggest Winner of the media reforms is… News Corp as usual

Call it Lachlan’s Law. One of many consequences of the government’s comprehensive package of media reforms announced over the weekend is that Ten becoming part of the News Corp family starts to look more likely than not, argues Mumbrella’s Tim Burrowes

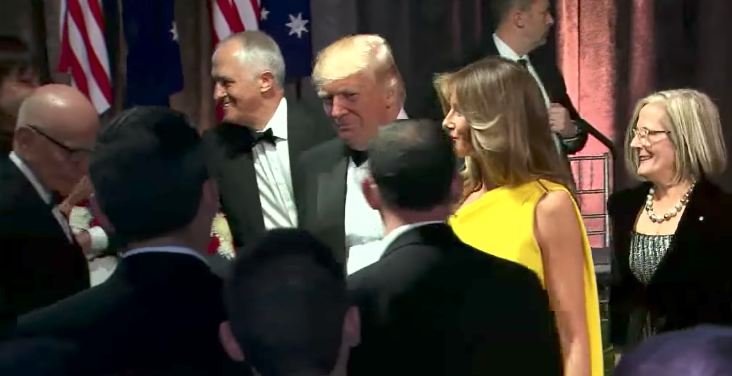

No wonder Rupert Murdoch looked so pleased as he shared a stage with Malcolm Turnbull and Donald Trump in New York on Friday night.

We’ve been here before.

Four decades after buying into Ten – and three decades after having to give it up again to pursue US citizenship – the path finally appears to be clearing for the network to return to the Murdoch family.

Ah, but the flurry of comments from industry insiders is at least comforting…

Thanks for this interesting explainer on television.

Does the 2 out of 3 rule still apply? And what are the implications for print and radio?

Hi George,

Thanks for the question. As I mention in the piece, the two-out-of-three rule would go.

The two big players in print are News Corp and Fairfax. News Corp under its current ownership is not a seller of print (except for the Sunday Times in WA, and I suspect that made it easier to do a deal with SWM on Sky News ownership). Which leaves Fairfax. Much of that will be decided based on the outcome of the current TPG shenanigans.

As for radio. I think that almost deserves a seperate piece. But the most interesting asset that might go into play would be the Fairfax-aligned Macquarie Media. On the one hand, a station like 2GB seems a great fit for News Corp, but on the other, I don’t think the company has ever shown much interest in radio assets. (Other than Lachlan’s successful personal investment in Nova of course.)

Cheers,

Tim – Mumbrella

Didn’t Stokes (via The West) takeover the Perth Sunday Times a little while back?

“The principle losers on this will be Nine and Seven …” Are we to assume you mean “principal”? There are few “principles” in the world of the broadcasting business!

Thanks Spelling Bee

Duly fixed.

Cheers,

Tim – Mumbrella

Separate.

They key to media is content. If Murdoch gets FTA he can leverage his global content rights at low cost. Especially if he gets a bit more control of Foxtel. The newspaper businesses are still the primary sources of news content and if fairfax breaks up Rupert will completely dominate.

The obvious missing reform was valuation of the FTA spectrum which is wasted in its present use.

I think something you could have added to your article was a note that none of this is definitely going ahead – the whole package will need to get through the Senate. Govt needs ALP support (they’ve said they won’t support 2 out of 3 going) or most of the cross-bench (who may have some unexpected and undeliverable demands). I think there’s still a lot to play out here.

Mumbrella jumping at media bogeyman. It’s 2017, not 1995 guys. Heard of Facebook and Google? Myopic, parochial analysis. Pretty disingenuous to claim it is ‘Lachlan’s Law”. Not only do Stokes, Fairfax and the entire industry support the package, but it leaves anti-siphoning intact, so not accurate to claim it’s a free-kick for News Corp.

So Facebook and Google are substitutes for existing media? Earth to Bob Stone: get a grip.

Alternatives or not, the evidence is there that these people have undue access to and influence over the electorate. It makes a mockery of true democracy.

<<>>

This, absolutely. Also the fact that the majority of content the major network produce is utterly awful.

The main point though, that News Corp and Rupert always wins – exactly right. It always does.

In your article you claim: “It’s just that, as is so often the case, it looks like the interests of the Murdoch family stand to be the biggest winner.”

Please explain the media regulatory wins for the Murdoch family from the last 25 years because I’m struggling …

Thanks Tim, very informative article.

One Question though, Ian Audsley the CEO of Prime Media has pushed fairly hard for the changes to happen but I would have thought that the laws were there to protect the regional networks from being overrun by the big three. What would be the benefit to Prime and the other regional networks in having the 75% coverage rule changed?

Many thanks Michael.

Hi Michael,

To be painfully pragmatic, the biggest benefit to Prime shareholders would be to increase the value of the company. Now it can be bought by one of the big networks, it’s arguably worth more. Which is why the shareprice went up 12% today. It doesn’t protect the networks from being overrun – quite the opposite.

Cheers,

Tim – Mumbrella

Great analysis Tim

News gets to buy Ten (after having lost $200m down the Swanee already) – lucky old News, eh ?

Although the 2/3 rule may have changed, the foreign ownership rules have not. And News is a foreign company. The grandfathering clause which applies to the newspapers won’t apply to new properties.

Assuming Lachlan can convince US creditors to sink even more money into a lossmaking terrestrial network – after slagging them off for the last 30 years, there would still be all the extra money needed to revitalise the programming.

You assume a renegotiated rights agreement with the Hollywood cartel would result in lower costs – I’d say you are wrong. New contracts are always more expensive.

Fox does not “own” content. It is only has rights to distribution. Most of the reality programs are franchises owned by European companies and licences are country specific. Even programs with the Fox logo at the end are not owned. The price Ten pays for “The Simpsons” is defined by Grace Films the copyright owner, not Fox.

I’m on the consumption side, not the production side. From my side, I can tell you nobody asked them to do this, nobody on FTA wanted them to do this, Nobody concerned about independent media is happy they are doing this, and we are NOT going to take a foxtel package of 55 sports we don’t give a shit about, to watch 2 instances of a game we do care about.

What we’re going to do (and I mean the generic we, not me specifically) is the same thing we’ve been doing these last 10+ years. We are going to quietly go on finding alternate sources of the content in disregard of the IPR rules, because the IPR rules are not reflecting what we want.

Blind freddy can see that this change is not motivated by FTA consumers. Its motivated by FTA operators and IPR content owners and their revenue streams and shareholders.