Who moved my pyramid?

This is an edited version of last night’s opening keynote to the Walkley Media Conference in Sydney from SMH editor Peter Fray

I was recently reminded of the six golden rules of how to become a good reporter:

Read, read, read – write, write, write.

That deceptively simple advice came from late Peter Bowers, relayed at his recent funeral.

That deceptively simple advice came from late Peter Bowers, relayed at his recent funeral.

Bowers brought politics, sport and the bush to life on the pages of the Herald for four decades, so he knew a bit about writing.

He never wrote a dull story.

And, read, read, read – write, write, write remains pretty sound advice.

But in an age where the internet delivers the world of journalism, for free or minimal cost, where it delivers that journalism wherever you may be and on multiple platforms, and where there has never been more competition for readers, the advice raises two pertinent questions which are:

Read what?

Write what?

How then do we tell stories that are relevant and present them in compelling, engaging ways?

How do we keep and connect with existing audiences?

And, at the same time, find ways to grow new ones?

And, on top of that, make sufficient money to pay for that journalism.

And if you thought I was going to answer that question in the next 30 minutes, then I must be a lot smarter than I look.

But let me give it my best shot.

You don’t have to be the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald to understand that something profound is happening to our industry.

A myriad of social and economic factors are having — or are threatening to have — a massive impact on the craft of journalism.

These are not all bad.

If you combine the print and online readership, there are more people reading the Sydney Morning Herald now than at any other time in its history. The same is true of other mastheads and broadcasters.

Many readers are not paying for it, of course, but that’s another and much larger discussion and something of a moot point: if you don’t have the audience in the first place, you’re not going to have any chance to pay for the journalism.

It’s not overly productive to blame the rise and rise of the internet for the daily challenges faced by newspapers around readership and circulation.

The internet is not to blame for the difficulty balancing work-life pressures, which, according to the recent Australian Work and Life Index, sees 60 per cent of female and 50 per of male workers feeling under consistent time pressures.

There’s no doubt, of course, that online gives many readers free and accessible information to news and views – and that many former print readers have migrated to the web.

No prizes for that observation.

But why waste time debating the pros and cons of either platform when they both clearly have a role to play in creating and delivering quality journalism, often to different audiences.

Anyway, it’s not as if there’s an option: the web is a fact of life.

And if, like me, you’ve discovered iPad apps such as Flipboard , which allows you to design your own social magazine, you’ll appreciate that that life is only going to become more complex.

Print and online can and must work together.

The real issue, then, how do we best connect with the readers.

What is our value to them – and how do they recognise that.

We sometimes seem to forget that ‘traditional’ journalism has been changing ever since it was invented.

I am just old enough to see at first hand the closure of The Sun, the afternoon Fairfax newspaper in 1987.

That was a sad day. As a young reporter at the Herald, I did not fully comprehend just how sad – or why it was no longer economic to print afternoon newspaper.

By the way, as a friend recently suggested to me, there might even be a case for afternoon papers, given so many of our readers don’t get to read that day’s edition until the evening.

I also once worked for the Bulletin magazine, a fine publication in its day, but which, like the Sun before it, had simply run out of sufficient readers and advertisers to make it pay.

So, will the same happen to morning newspapers?

Well, frankly, it could. It has, as we all have seen over the past two years, in several cities in the United States.

But it won’t if we meet the challenge of redefining what is journalism, especially in print.

And just in case you’re not interested in the future of print, let me just add that print journalism, rightly or wrongly, drives radio, especially talkback, and largely, give or take the odd Laurie Oakes scoop, sets the news agenda for television.

At the risk of sounding high-falutin, I’d argue that it is the creative bedrock for the national discourse – and until we have a journalistic alternative, and Twitter isn’t it, it will remain so.

The challenge, then, is to redefine what we think we know about print, keep and enhance the bits that work and kill off the bits which have been superseded.

We have no do-nothing option. We need to change.

Let’s start with the basics: why do people buy a paper?

There’s a bunch of obvious answers – habit, desire to be in the loop, the lifestyle sections, sport, business, the TV guide etc. The idea that your newspaper is a reflection of your world view.

And, of course, then there are the letters, the readers’ columns, such as The Herald’s Column 8 and The Heckler.

And if you’ve ever tinkered with a long standing crossword, as I’ve done, you’ll know how important they are.

We know a lot of our readers actually read the stories. That’s a crazy statement, I know: people buy paper to read articles.

But we also know two things:

One, many readers once considered the paper the only source of classified advertising and the only place to get the news;

And, secondly, we know keeping readers is a constant challenge, and that, given half a chance, some readers, especially those with time constraints, will feel okay about not reading the paper at all, especially the Monday to Friday versions.

This isn’t a crisis.

It is an opportunity.

It is our opportunity to start re-imagining some of the things which we’ve taken for granted.

Some of these are very basic, simple.

You might have thought it was ‘sorry’, but increasingly, ‘yesterday’ is the hardest word.

It begs the question: if it happened yesterday why should I read it today?

Haven’t I already heard or seen or read this?

Haven’t I already read this online?

Hopefully, the answer to that last question is no, or at the very least you read a different version of it.

Do we need to say yesterday?

Why date the information, why make it older than it already is, why read a paper if it is filled with ‘old news’.

Does this mean we can’t report what happened yesterday?

No, of course not.

There would be blank pages in the paper if we didn’t.

But wouldn’t it be great if we could fill the lion’s share of the paper with things that looked forward or, better still, were entirely special — or at least special to print in that moment.

To my mind, this means:

- Greater commitment to investigative journalism – across platforms

- Greater concentration on campaigns and series

- And more out and out specials.

Image: @jlizier

I have in mind here things like our recent election special lift-out which posed 15 questions the election should be about – but isn’t.

But to drive such change we need to be open to re-thinking some of the basics.

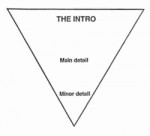

The inverted pyramid is the basis of our reporting structure in news.

The all embracing lead (25 words or less), the next par supporting the lead, the next that broadens or explains, the next which introduces some new, a quote or two etc.

The all embracing lead (25 words or less), the next par supporting the lead, the next that broadens or explains, the next which introduces some new, a quote or two etc.

The whole method is an efficient, economical and universal way of answering the questions who, what, where, when, how and why.

The five Ws or if you report in Melbourne, the six: what team?

This is a system perfectly designed to tell us about Yesterday, about what happened yesterday.

But what if we cared less about yesterday – because we don’t want to bore people with stuff they may have already read – and more about today and tomorrow.

What if we were primarily concerned with the WHY and the WHAT Next?

Because the web or its current model is going to struggle to tell you the why and the what next – because it deals with the instant, the breaking news and views.

In this respect, the web is more akin to radio than print.

My point here is that in print we need to aim for greater authority, thought – and, hopefully, engagement.

And we shouldn’t be hung up on the 5-600 word page lead as the most efficient way to get it down.

The readers want more – and less.

Yes, we do tend to overwrite. We do have a tendency to equate length with understanding and quality, or, conversely, to think if it’s long it must be good.

That’s not to say if it’s short its always better.

But we have to be smart and judicious – and innovative.

An example:

David Marr, a national treasure, is writing about the hole that opened up in the road Bellevue Hill.

Under the headline, Sand castles – the upper crust hits rock bottom, he writes:

“As catastrophes go, the great Bellevue Hill landslip was extremely civilised. The only reported casualties are two cars, a lamp post and a tree.’’

It is only 420 words long, and the word yesterday doesn’t appear until par 16.

Now, you might be thinking, that’s all well and good, but I’m not David Marr.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t aspire to be your own David Marr.

The artistry and craft in that piece is not the stuff of Walkleys.

But it is a wonderful example of what we all should be doing – telling relevant stories and not wasting a single word.

There are many ways of telling stories.

My point here is that some readers — many, not all – are open to having information delivered in new ways, provided in doing so we don’t destroy the quality and reliability of that information.

I have long thought we have to do more – more with every story – than simply headline, picture, words.

How boring is that? How uninviting. How taking a lend of our readers valuable time.

By this I don’t mean let’s over-engineer or over-design each yarn.

A few re-designs ago, Herald reporters were asked to write a few pars with each story, known as the story so far: a precis of the key points.

It did not take long for such requests to either fall by the wayside (forgotten by sub or reporter alike) or be greeted with outright derision.

That to me is a challenge to editorial management: changing the culture requires constant attention and constant leadership.

But we have to do all we can to give ourselves a chance to be read.

So, let’s tell stories using every weapon we have, be that a picture, some great words, a graphic, a marriage of the graphic with the picture, a marriage of the headline with the graphic, just a graphic, just a picture or an illustration, a cartoon, or white space – or some black space.

You might think this is just design trickery.

I agree that all the design in the world will not save us if we don’t have great images and great words to work with, and quality journalists to provide them.

So to that end, I ask – I implore – you to think about every word you use.

Reporting is not a passive occupation. It should be at every level a creative pursuit.

Neither for that matter is editing.

We are all on a journey and we must all learn to adapt and broaden our skills.

Which brings me back to online.

Some of the things I wish to ban from the paper still have plenty of relevance to the web. Not the word yesterday, but the inverted pyramid or any other method that delivers information rapidly and accurately.

In the future, I have no doubt that some of the most successful journalists – no matter what their jobs – will be able to satisfy the needs of online for fast turnaround news, commentary, video AND the paper’s desire to give readers more: more unique quality stuff.

And even if we stopped printing, we’d still need to produce the highest quality content – across all platforms, meeting all needs and markets.

What we need to find out is how to pay for the making of that content.

I know most of us want to be part of online.

Many of us already are.

Many of us already understand the huge potential that rests in online and how it can assist the printed version and vice versa.

For instance, there is a great future in data based journalism: in harnessing the power of online to unearth trends and patterns, to cut and paste information that both illuminates facts and stories and delivers relevant information to readers.

I’ve been asked a few times recently to describe my ideal reporter.

It’s easy: he is Rambo; she is Rambette.

Why?

It is obvious isn’t it?

Both Rambette and Rambo are multi-platform types able to use a variety of tools to maximum effect.

But there is also something else that appeals: they know how to catch and kill their own.

They can go out in the forest or desert and come back a bit soiled but successful, having done all the work themselves.

They can in other words go out, take risks and tell their own stories – in their own unique ways.

I think Rambo might be on to something here.

At least he’s not going to die wondering.

I don’t intend to do so either.

Linkedin

Linkedin

of the many calls for change in newspapers this is one of the clearest and most engaging I’ve seen. it’s good to see somebody encouraging structural change rather than encouraging readers to pay for old news in app form.

User ID not verified.

A great read – but with all due respect, I think he misses a crucial point. He seems to want to look for ways to maintain/increase the appeal of the print edition. Presumably, this is because the print edition is where his revenue base is.

The differentiation he should be making is not print/online but free/paid. I would happily pay for extra content, quality, features etc, but want it in the convenience of an online format. Granted, not all people are willing to pay for online content, but isn’t asking ‘How can we extend the life of print as long as possible?’ the wrong question?

Surely the right question is ‘How can we get people to pay what our quality is worth?’

User ID not verified.

I agree with other Andrew. People want quality they dont have to pay for. How can we build quality in a ‘give it away’ society?

User ID not verified.

Interesting piece. I love this quote:

“there might even be a case for afternoon papers, given so many of our readers don’t get to read that day’s edition until the evening”

Last time I checked, the 3rd highest-circulating weekday newspaper in Australia was mX – distributing 232,000+ copies every weekday afternoon across Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane to mainly 18-39s (sorry, sales pitch over)

Peter, I think you’re onto something 🙂

User ID not verified.

It’s all very nice. But the problem Fray has is that the Herald is not compelling in its basics. The “news” is all extremely predictable. The “analysis” is trite. The “comment” is often childish or pathetically pretentious. The make the Oz look good, which is in itself tragic. Muck with the form all you like. It’s the substance that has gone missing.

User ID not verified.