Agencies boast about their happy cultures – so why are staff so miserable?

As a new survey reveals evidence of widespread depression, anxiety and stress in the creative, media and marketing industries, Adam Thorn argues bosses are more interested in their own PR than tackling the real issues.

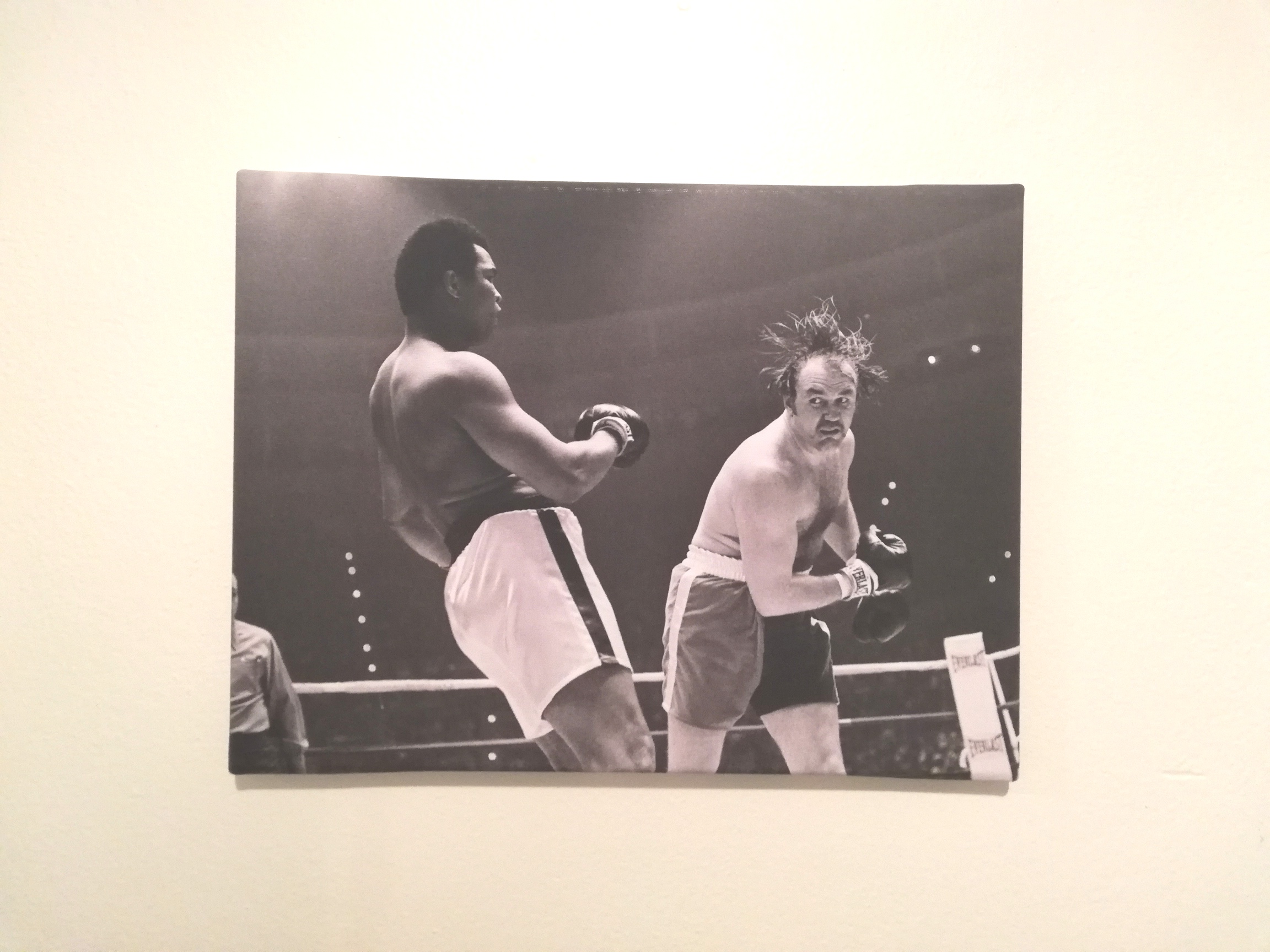

Six weeks ago, I moved into my first apartment on my own, which, approaching 32, felt like a major life milestone. Always thrifty with money, I’ve tried to kit the tiny unit out as economically as possible. The fridge, TV and sofa were second-hand from Gumtree (my mates hurling the three-seater on the roof of the GoGet and secured with surf straps), while the rest of the furniture, cutlery and what-nots were bought from Target and K-Mart. In fact, the only thing I really spent money on was a printed canvas I designed myself of a little-known boxer called Chuck Wepner, which now hangs on my bedroom wall.

My canvas showing Chuck Wepner’s greatest moment

I tracked down and interviewed Wepner eight years ago when I was a journalist at British lads’ mag Loaded after first spotting his story in a small column tucked down the bottom of the BBC Sport website. Wepner was a chubby amateur juggling a day job from New Jersey when, in 1975, he was given an improbable shot at the heavyweight title against Muhammad Ali, in his next bout after The Rumble in the Jungle. Nicknamed The Bayonne Bleeder because of his propensity to cut after taking a punch, Wepner told me he’d scrapped with as many men in the streets as he’d fought in the ring.

That is a very well-written piece: engaging, insightful and leaves you wanting a little more. Great work.

This article is very timely. I’ve found the more emphasis an agency has on trying to win workplace culture awards the more toxic the environment. I’ve worked in a big Sydney agency and the glossy submission seemed a world apart from the reality. A long list of branded initiatives some of which looked like maybe 2 people had experienced them and they certainly weren’t having the effect they claimed. My advice is to look past this kind of stuff and get to speak to as many people as you can at the agency before accepting an offer. Toxic behaviours are top down so if you see a bit of revolving door with senior roles this is also a bit of a clue to problems within.

It is possible to find an agency full of kind and supportive people. They’re rare but when you find one you’ll treasure it forever.

This is such a great piece about a very under publicised topic.

Depression and wider mental health issues are rampant in this industry and it often feels as if it keeps being swept under the rug.

Good job calling it out Adam, and I hope agencies start actually caring for their employees instead of just saying they do.

Finally someone is honest enough to talk about the truth of what goes in our industry. From personal experience, those ‘award’ places that call themselves ‘creative media agency’ are the worst of them all, as they value awards and not good work or staff. They bluntly lie saying they have 80% staff retention rate when the truth is no one has been there for over a year. Lucy the robot places make our industry ashamed and staff lives miserable.

You were right when you said external issues are a major factor in mental health issues. The difference I think is agency. Not ‘agencies’, but personal agency. The only person putting pressure on Chuck was himself. If he trained unsociable hours, was exhausted 24/7, got a hairdryer blast, it all came from him, to him. That sense of being in control of your own success and failure is what makes it fulfilling.

For the rest of us, that pressure comes from outside. From the bosses, the clients, even the colleagues who side-eye you when you leave at a reasonable hour. We are not Chuck Wepners in agencyland. We don’t reap the rewards of our own success but we do catch shit for others’ failures. The struggle isn’t fulfilling here because we’re always fighting someone else’s and being told it’s ours.

I think this is a great piece – very thought provoking. I come at it from an interesting place in that I suffered significant mental health problems when I first started out in my career, and now I manage an agency with a whole lot of people.

I agree that many workplace scenarios can precipitate mental illness. I was relentlessly bullied in my first job, and it caused me to spiral in to a world of anxiety and depression. BUT, the reality was, from my early teens, I had been avoiding many issues for years, and the bully at work was ultimately the final straw. I had zero to no resilience and it too the structure of a full-time role to highlight that.

So, it can be work, but people starting out in their careers also need to be encouraged to understand themselves and their level of resiliency and what they might need to work on to survive in full-time land. Because full-time work is not easy.

Now I oversee a whole bunch of juniors, it’s hard to want to see the best out of them, but not transcend the professional/personal barrier. I often see juniors do what did when I started full-time work ie. get shit-faced all weekend and then spend the working week going through the spiral of depression, tiredness, anxiety – then emerge full of hope and optimism because Friday night is on it’s way. As their boss, I can’t tap them on the shoulder and say, hey, did you ever think what you are choosing to do outside of work may be impacting your mental health as well? But I can’t. But it is definitely part of the puzzle.

Which bring me to my last point. Sometimes employees, particularly junior ones will view ‘culture’ as something that is seperate to themselves. That’s rubbish. What every employee brings to work everyday, is what contributes to the overall culture of the business. It’s not just agency bosses that dictate these things, it’s everybody.

Thanks again for the article.

I’ve always said agencies that talk about their ‘amazing culture’ which is full of bells and whistles i.e. programs, free breakfasts, snack bar etc. is the equivalent of a boyfriend giving you a bouquet of roses, and then punching you in the face.

‘But I gave you a bouquet of roses! What’s the problem?!’ – urgh… maybe get the basics right first and then worry about the add-on extras?

It’s also just bribery, why do you need all these bells and whistles to make people work for you?

The best places to work do these things as bonuses, but they don’t replace the basic need of not being an arsehole. Respecting staff, listening, being fair and reasonable, creating a culture where your staff’s time is respected and their life outside of work is respected – all those things are free and is what’s genuinely going to make staff loyal.

Couldn’t agree more Samantha!!! The analogy you’ve used is perfect.

Very well articulated thoughts penned down with reality. Being in communications, I have faced shitty challenges adding to mental stress and adding unnecessary unwarranted demands.

This article is so on point it’s almost scary. Toxic agency culture and roles that destroy the soul are two huge factors in the high rates of depression in the industry.

It’s also worth pointing out there’s a massive difference between ping-pong table culture and genuine team camaraderie. Imagine if a plane-load of agencies types crashed in the Andes. The flesh eating would start before the bodies were cold.

Yes, yes and more yes! I worked for an agency that was rife with bullying and abusive emails about budgets every week, the pressure made people nasty and ruthless. Yet, they are a BCorp and a Great Place to Work. I don’t know anyone who enjoyed it there. When I left recruiters told me I deserved an award for staying there for a long as I did. Stunned that the business thinks lunches and free bicycles make a good culture. It’s not the ‘stuff’, it’s the checking in and the kindness and the support to others in the business that makes a culture.

Could not agree more with this piece and everyone’s insights. Having worked both agency and in house with a variety of “interesting” management experiences, bosses who provide genuine support and encouragement always bring out the best in staff. When toxic cultures come from the top, how can there be accountability and change? It’s a battle not worth fighting. It makes me appreciate my great workplace so much more. Thanks again for this piece.

This is probably the best thing I’ve read on Mumbrella, not just because it’s brilliantly written but it also touches a nerve.

I worked in a highly celebrated creative agency about 10 years ago when I was quite early in my career. I was attracted by the awards and the ping pong table and the cool office and figured it’d be a good place to cut my teeth.

What I didn’t know was that the culture was just so appalling and toxic it would drive me to depression. It was so unbelievably cliquey: one person was great friends with the CEO’s daughter, another girl was having an affair with the (married) MD, two of the apparent gun creatives were bought in from some other agency and given a license to be arseholes to absolutely everybody who wasn’t in the ‘in crowd’, and so on.

I was just a young bloke about 2-3 years into my career and was thrown into the middle of the cesspool on a $50k package and it damn near broke me. I didn’t realise it til afterwards, but I wound up with depression as a result of the extreme hours, being barked at by ego tripping creatives (as if writing a press ad for a two-bit property development somehow makes you Michaelangelo?), excluded from the private school ‘in crowd’ after work events, etc.

I went into my shell a bit as a result, which compounded things. I recall one time when the aforementioned ‘gun’ creatives printed out the names of everyone in the office with a colour pallet next to them, and stuck it on the wall. The colours represented the person’s personality, and there was a brief explanation. My colour was grey, which represented my “boring silence”. The MD celebrated and encouraged this shit and stoked the fires of the cliquey behaviour.

After working two consecutive days from 5am – 2am (on a pitch, which we didn’t get), I got asked to resign. I reckon I’m reasonably headstrong but the place just sucked the life out of me like nothing else I’ve ever experienced and no doubt it affected my performance.

But – getting the arse was the best thing that ever happened to me. Wound up with a great job after that which led me down a much happier path. I now do interesting & satisfying work, earn more than the (now divorced) MD, don’t work with a bunch of absolute germs and drive a fast car home to my kids before 6pm every day in my big new house. 🙂

Hi everyone,

Thanks so much for your thoughtful comments – I’ve been really taken aback by the interest in this.

I would like to follow this up as a proper feature, and it would be great to interview people about their experiences of bullying – whether or not that’s anonymously.

If you would like to help, email me at adam@mumbrella.com.au.

Thanks,

Adam Thorn

Great article – always love reading your yarns Adam. As the comments above show, the bullying aspect of toxic workplaces is all too pervasive in our industry but I like to think that the tide is turning on the ridiculous hours – at a glacial pace, but turning nonetheless. Yes, there are still plenty of places (agencies) demanding 14- or 16-hour days from their staff, but I don’t think it can last forever – simply because younger staff refuse to do it.

I’m 34 and lead a team of mostly 22-30 year olds in an in-house marketing team for a large national brand. The majority of them are out the door at 5pm (6pm is a late finish for them) and they are visibly horrified when they hear my tales of regularly starting at 7am and finishing after 10pm during ‘the olden days’. They do not see it as a badge of honour and nor should they – I was miserable, permanently exhausted and on the fast-track to burn out.

And while they’re still happy to socialise as a team, go for lunch together, etc they are much less interested in getting blotto than I was at their age. All the research suggests that the younger end of the millennial bracket are more conservative than previous generations and that is certainly what I see every day – as do friends of mine who also manage younger teams.

So if culture comes not only from the top but also from staff, then this fills me with a tiny bit of hope that things won’t always be the way they have been!

Agreed – your experience (and age, employer type and team structure!) is identical to mine. Today’s 20 somethings seem smarter than I was – they just won’t cop it. They still work hard and will grind out big weeks when reqd, but if it’s *not* necessary they don’t feel the need to hang around to look “good” like I did.

Terrific and timely read. Great stuff Adam. Please do go ahead and write that full length feature…

Loaded magazine was as guilty as any publication for promoting the ‘perfect’ male lifestyle of attractive women, gadgets, fast cars, booze etc and falsely raising young men’s expectations to an unattainable level,making them depressed when they couldn’t live up to a lifestyle that few actaully have and even fewer genuinely enjoy.

The whole lads cultrure made it harder for men to talk about their problems as it wasn’t seen as the thing to do. Plus it added significantly to the well-publicised ‘porniifcation’ of society, leading to pressure and mental health problems for girls, a growth in anorexia etc.

In other words this guy is a total hypocrite to talk about oppressive culture and mental health problems as though he wouldn’t dream of contributing to anything that could exacerbate the issue.

He’s not even a good writer – vis-a-vis the long-winded intro to this piece which thad me skimming through after a while to find the two paragraphs that actually discussed the subject in the title..

Stupid comment.

But let’s entertain your point and say he is a hypocrite, you can still be a hypocrite and be right.

For example, if I were to murder someone, I can still correctly condemn murderers and point out what they did was wrong.

Anyway I’m also pretty sure David Brent killed the phrase “Vis-a-vis”.

Gareth, go and get the guitar.

..and thought-provoking.

was nodding my head while reading, thinking about my (very long) time in the industry as an employee working across many agencies,..then more hesitantly reviewing that same time as a manager and boss.

Great article and many valid points. Can’t pretend though that I don’t get irked by the simplification that the beer fridges and ping pong tables are there only as ground cover for the remorseless ‘man’ to go about his evil slave driving. They are there to try and make (what has become a very) hard industry more bearable, to continue a tradition of fostering creativity and to try and ensure that advertising as a profession remains a cool place to be. Undoubtedly there are some absolute arsehole bosses out there, and I know for a fact some of the people I’ve ever worked with think I’m on of them. Equally however, there’s a fair few self entitled snowflakes rocking up at agencies who do nothing but bleat endlessly that the bit where we said it wasn’t ever going to be a 9 til 5 turned out to be true. If we need something to blame its media fragmentation, margin pressure and the relentless pace of digital reinvention. Its getting harder and harder to make less and less profit and until agencies wake up and radically change the model, everything in this article is only going to get worse. I now work client side, running an in house team blended with in-sourced and out-sourced consultants. There’s no ping pong tables, its still hard work, but its a lot less toxic. Dunno what that means but I reckon it means something. Thanks for thought provoking read

…you can’t even begin the imagine! Oh the irony of your comment wrapped up in the publication of this report.

In the same way Atomic 212 imploded with lies and deception – so too should some agencies regarding their culture.

When sexism and misogyny are baked into the leader of the business it creates a culture of fear and bullying no matter how many ping pong tables or dress up days there are.

32 years of age and he’s moving into his first unit by himself.Enough said really.

No, not enough said. Go on, explain what you mean and how it relates to mental health in the workplace.

Please go speak to some people in their 20s and 30s who don’t have partners and get some perspective on how expensive and unattainable it is to live out of home, by yourself in a large city when you work in the media industry.

People live in sharehouses well past the age of 32, especially in the over the top expensive Sydney and there is absolutely nothing wrong with either that or staying with your folks toake ends meet on shitty wages. You have nothing to base your bitchy judgement on, and you are detracting from the importance of the topic.

Take a seat.

Great article. 20 years in the industry I met far more nice people than arseholes. But it just takes one, and he just has to be a group head or creative director and your work life is hell. because it’s all subjective, they can dismiss your good work to suit whatever agenda they may have–including getting rid of you. I always felt like a circus lion up on my haunches performing , knowing that in a blink I could eat the arsehole with the whip alive.

I was bullied by my Account Manager in my second job (I was her AE). I didn’t realise it at the time and just assumed that she was a ‘difficult personality’ (as I was told by HR). I was mocked about my work ethic every few days to my face, and she would drop her projects onto me while she took extended lunches to then belittle me for not completing my and her tasks. She was also very close with the MD and practically untouchable in the agency. I would finish (late) every day feeling almost lifeless and dreading being back in the office the next day – it killed my confidence, self esteem, social life and caused a lot of friction between me and my girlfriend at the time.

It wasn’t until I left that agency and worked under the most amazing and empowering managers that I realised just how bad things were, and what workplace bullying looked like. It took a good 18 months for me to really come out of my shell again.

Articles like this are hugely important for the industry and especially young professionals who may just think that “this” is just the way things are. Because the problem of workplace bullying and gatekeeping isn’t going to go away until toxic people can no longer hide behind the: “oh this is just how it is in advertising/PR/marketing”.

Unfortunately, experience can only be gained by experience.

I worked under a toxic boss at a publishing company. I put this down to the pressures he faced. It wasn’t until I worked at an agency with incredible leaders, all of whom faced 10x the financial pressures my previous boss faced, that I realised an important lesson: some people are arseholes and that’s that. Walk away. Life way too short to indulge these clowns.

I’ve not seen too many companies for whom “amazing cultures” are more than marketing speak. Especially true for agencies that are trying (generally) even harder than the general business community to look cool.

It is changing, however. I see a correlation between with how little an agency is full of themselves and staff happiness.

Honestly, as a freelancer (and pretty happy and positive person as a general rule), I can count on one hand the places I’ve worked in in brand / advertising / media that have a positive culture.

Despite their desire to project a ‘we’re family, we’re so woke, we’re making each others lives amazing’, spend a day in any agency when the budget hasn’t been hit for that month and you’ll see their true colours.

I’ve met CEOs who have trashed people I’ve worked with within 60 seconds of meeting them, I’ve worked with a GM who unapologetically sold me out on a phone call with a client because he didn’t want to get in trouble, and I’ve worked with a CEO of a brand agency who genuinely does look after his staff – who seem to have a much lower level of stress outside a general deadline hustle.

My biggest problem has been with men who are extremely willing to ignore and enable harassment against women. The number of potential lawsuits I’ve seen in action is astounding. If you think that’s not still rampant today, you’re dreaming.

Thanks so much for writing this Adam. Good to see this article getting so much traction as it’s clearly resonating with a lot of us.

I agree with everything in here. During my time in agencies in my earlier years in the industry it became increasingly obvious that alcohol, games and dogs were a way to paper over the cracks.

If a work place really cared about your well being, you would have healthy work life balance and earn a reasonable salary, rather than the shockingly low packages agency execs and managers earn. Young people in agencies who ask for pay increases are frequently told by their bosses that their current salaries are reasonable, when they are definitely not.

In my experience junior to mid-level team members are often put down and belittled so that they question their worth and don’t ask for pay rises.

This article couldn’t be more timely. I recently started at a new agency and the stress and pressure is suffocating. The senior directors and department heads are all close friends who spend their weekends together and bitch about everyone else. Nothing is ever good enough and we don’t get anything but negative feedback, on top of even more work. Someone left the team and because of budget issues they’re not being replaced but when we ask questions, we’re told “we’re not that busy. X office in X country does 2 x as much billings as us with the same amount of people so we can do more”…. as though billing’s equate work and there’s no other variables.

Agency world can be great fun with the right people, culture and support however it can be a cesspool when all those things are lacking.

This article is a knockout… it exposes the lie that is alive and well in the creative sector.

I worked in an agency that pushed their ‘culture’ hard. But it was the culture they cultivated that ultimately led to a turnover even higher than the agency average. They claimed to hire almost solely on cultural fit, they organised and encouraged boozy social occasions at least once a week and they encouraged a boisterous, jokey and familiar atmosphere.

At the start it was fun, dizzyingly so. But those ‘cultural fits’ all turned out to think the same, with the same relentless, tough and sometimes bullying attitude towards juniors or anyone who was a bit different. The rite of passage was folklore, and workload targets at 140% capacity were grinding and never achievable, but the critique was personal. Regular boozy nights out blurred the line between what is professional and what is harrassment. And that jokey, familiar atmosphere gave some the green light to swear and make personal or sexually inappropriate jokes about juniors not really able to defend themselves.

It took six months after leaving for me to realise how much that environment affected me. Many others I later spoke to had the same issue. I had anxiety and my self esteem was shot. Despite being told making the move in-house would be career death, I’ve since worked in a number of large organisations that are not perfect, but where behaviour like that would absolutely not be tolerated. And far from dying, my career has accelerated.

My advice to young people trying to stick it out in agency for as long as they can: if your mental health suffers it is absolutely not worth it. If you can’t hack it in agency land, it’s not the end of the world.