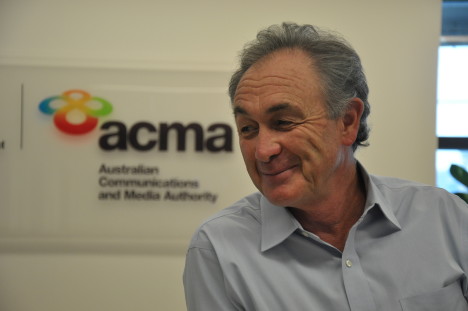

‘No regrets’: ACMA chair Chris Chapman on a decade of keeping the media industry in line

For a decade Chris Chapman has led the media watchdog as it attempted to navigate an increasingly complex landscape. A fortnight before he finishes up in the role Chapman sat down with Nic Christensen to talk about his legacy and the future of the regulator.

Ask senior people in the broadcast industry for their view on ACMA boss Chris Chapman and it is immediately apparent there is no-one who is ambivalent.

After ten years heading the powerful media and communications watchdog the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), Chapman has seen countless media owner CEOs and executives come and go, outlasted six prime ministers, five communications ministers and six departmental secretaries.