25 things that have changed about journalism during my quarter century as a hack

Mumbrella’s Tim Burrowes began his media career 25 years ago today. He reflects on the changes journalism has seen during that time.

Mumbrella’s Tim Burrowes began his media career 25 years ago today. He reflects on the changes journalism has seen during that time.

A quarter of a century ago, I was feeling pretty nervous.

A shy 18-year-old, who tended to blush if somebody spoke to me, I’d somehow mumbled my way into my first job in newspapers.

Monday July 10, 1989 found me walking in through the door of Penmark House, the former flour warehouse that was the headquarters of the Aldershot News.

Feeling a little nostalgic, last night I looked at the building on Google Streetview. It’s derelict, which moves me more than I would have expected.

On this day 25 years ago, I couldn’t believe my luck.

On the verge of failing my A-Levels (they’re a bit like the HSC) and unlikely to get into university as a result, I’d somehow talked my way in as a junior reporter on the basis of little more than working on the college magazine and an unlikely claim about my typing speed.

As I waited in reception, all I had to do was avoid getting found out. (When I think about my unhealthy work-life balance, I realise I’ve spent the subsequent 25 years still trying to avoid getting found out.)

And I now realise I got in just in the nick of time to see the whole journalism world change. I happened to start my career in the UK, but I think the trends have been the same for journalists across the developed world.

Mostly, I didn’t notice at the time – certainly not during the formative five years I spent working for the Aldershot News. Please forgive me this huge piece of self indulgence. With the benefit of hindsight, these are the changes that mattered for journalists…

1. Layers

Of everything that’s changed with technology – and I’ll come on to that – it’s actually an organisational thing – the removal of layers – that has most profoundly changed the product.

Take a look at the top floor of that derelict building. See the window third from the left, with the stickers on it? That’s roughly where my chief reporter sat. For the first couple of years, nothing I wrote would go any further without her scrutiny.

We were on the Farnborough desk. It had been her patch for years, so she knew the people and the politics, and she was likely to catch most of the howlers I made.

Only then would it get through to the terrifying Glaswegian Scottish news editor who sat at the window on the top left of the picture.

He would also scrutinise my copy (I still have a copy of the memo he wrote me about the correct spelling of the word “liaison”) – not only for accuracy (he’d been with the paper for decades) but also for angle.

Only then would it pass to the back of the building, still on that top floor, where the sub editors would sit in a room foggy with cigarette smoke.

The sub editor who would then get their hands on the copy would be a former reporter who again knew the patch intimately.

And after they’d subbed the story for length and sense, only then would it be seen by the chief sub before going across to the printworks, where the editor would see the piece on the stone.

That’s a lot of layers to hone copy, ask questions and catch errors.

By contrast, when I hit post at the end of writing this piece, nobody else had read this before it was online.

2. Training

Allied to that is training. Not only did I get drilled every day by people who had the time – and willingness – to do it, but they paid for me to go off for three months and do a full time course. By the time I qualified as a journalist a couple of years later, I’d learned from people every single day and been taught the essentials of public administration, media law and interview skills.

I doubt there are cadetship schemes that would take on an 18 year old with no qualifications now.

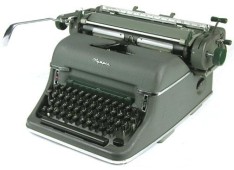

I arrived just in time to train on a manual typewriter. It looked a lot like this one.

The way it worked was that you took a piece of folio paper, about half the size of a piece of A4. You piled on a piece of carbon paper, followed by another folio. And you repeated it one more time.

On this folio, you could fit two or three paragraphs. You could use correction fluid for a minor error, but otherwise you had to rip it up and do it again.

The only word processing available to you was shuffling the order of the folios.

When your story was written, you’d staple each of the three piles of paper together, keep one for yourself, and give the other two to the news editor. He in turn would keep one and pass the other to the subs.

When deadlines were tight, the news editor would snatch each folio from your typewriter and walk it through to the subs.

It certainly taught you how to write cleanly.

4. Spikes.

![]() They were a thing. Metal spikes you’d keep your folios on for future reference.

They were a thing. Metal spikes you’d keep your folios on for future reference.

That’s why old journos like me keep their source material emails in a folder called “story spike”.

5. Computer networks

A while before the internet began to spread, computers arrived in newsrooms. I reckon it was early 1990 at our place. They were networked, so you could file electronically. It also meant the end of the typesetters’ jobs at the print works.

6. Faxes

The fax machine had just arrived in our newsroom when I joined. Initially, nothing used to emerge from it, then the PRs (not that there were as many of them) began to start sending press releases. I estimate that the fax deluge peaked about ten years ago. When we moved to new premises at Mumbrella three years ago, we didn’t bother to take the fax machine with us.

7. Phone boxes

If you saw a fire engine go past when you were out and about, you could try and follow the trails left by splashes of water, or you could stop at a phone box to ring fire control – a number you had memorised.

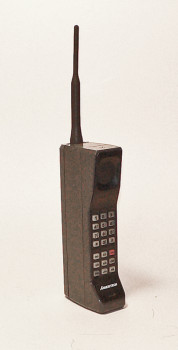

I was the first journo in our newsroom to buy myself a mobile phone in about 1992. It was a Nokia and had almost the same dimensions and weight of a housebrick. It cost me a hundred quid, which felt like a lot then. Particularly when it got nicked from our photographer’s car a few weeks later.

One lunchtime, I saw a very early example of the opportunities and limitations of that instant communication.

As I drove along a main road, a tree blew down ahead of me. I phoned over a paragraph about the road being temporarily blocked and it just caught the paper, which was going to press.

Within minutes, the winds increased to hurricane force, spreading chaos to much of Southern England.

By the next morning – when thousands were waking up without power – our paper carried the news that a small tree had fallen over.

9. Copy takers

There was a very specific technique for phoning over copy. Point. You would get put through to the copytakers. Point. Par.

They’d ask you for a catchline. Point. Par.

And you’d start dictating, comma, including the punctuation as you went. Point. Par.

Ends.

10. Phone technique

You had to work the phones. If you needed to look up somebody on the electoral roll, you’d ring the local reference library and persuade them to examine it for you.

If you wanted a quote from somebody, you had to talk to them.

At first, I was so shy, I’d sneak into the cuttings library to make my calls where nobody else could hear me.

The ability to email somebody to ask for a quote, tends to make for lazy journalism, I think. Inevitably, you get less colour – and less of a connection – than if you actually talk.

11. Cuttings librarians (and libraries)

Looking at that picture of the derelict Aldershot News, the fourth window from the left was the cuttings library.

Along with the typesetters (and most of the subs), the cuttings libraries are long gone. You’d spend hours trying to track down a previous story. For some reason I was obsessed with the Surrey Puma file…

All that info would now fit on a thumb drive of course.

12. Photographic departments

That’s the window to the top right.

I suspect local paper journalism is more lonely now. At that point, there’d almost always be a snapper with you if you left the office.

They’d have seen dozens of trainees before them and would conversationally ask the interviewee the bloody obvious question you’d forgotten to pose.

The idea of doing a big story without a photograph to go with it would certainly not have occurred. So I’m among those sad to see Fairfax’s plans to outsource much of their photography to Getty Images.

I used to carry an instant camera in my pocket, and even got to use it on a couple of occasions when something dramatic happened, but there was no substitute for a real photographer.

13. Editorial independence

The ad teams were on the floors below. If ever an advertiser rang our news desk and preceded an attempt to get publicity with the words “I’m an advertiser with you…” the news editor would transfer the call straight to the advertising department before they could say anything more. Sometimes the process would occur two or three times until they got the message.

14. Shorthand

I can’t think of a single skill I’ve got more benefit from, even today. It’s still quicker to take a shorthand note and read it back as you write the story, than it is to record and transcribe. Even now, I use it almost every day of my career. Yet few courses seem to offer this as a core skill now.

15. Time

Along with the reduction in layers, time is journalism’s big loss. With newspaper economics allowing (and demanding) big teams, you could spend time getting to know a patch.

We’d bring free copies of the paper out to the fire station, the local nick and the ambos. We knew them all. As a result, the station officer would have one of his men call me at home if there was an interesting fire. They’d even let me come out on calls with them.

The ambulancemen would look out of the window if we wanted to take a peek at the accident report. The cops would tell us what had really happened.

You’d go to local councillors’ homes and drink tea with them.

Indeed, there would be a journalist in every council meeting and covering every court case.

We sometimes wasted this time. There were certainly more long lunches with colleagues rather than contacts. Most Friday afternoons I used to sneak off to the cinema. There were staff who used to doze at their desks.

16. Time lag

You could write something and it would take days for the bomb to explode. If a complaint came in and you’d messed up, you would feel like somebody else had written it. Now of course, publishing online means that the world will tell you about your typos in seconds (you just watch…).

17. Democratisation of media

The single most significant change for journalists is the ability for anyone to get their story out.

To be independent then, you’d need to be able to afford to print your own mag or newspaper. Starting on your own would probably mean putting your house on the line. Now, of course, anybody can start a blog, and if that’s too much trouble, share on Twitter.

18. One-way conversations

It used to be that we decided what was important to readers and told them. They bought the papers regardless, or maybe sent in something to the letters page.

At the same time though, we were taught to write for the readers. Every story we we wrote, had a picture of those imaginary people (they were called Sid and Doris Bonkers), and what would matter to them, in our mind.

Social media has made that two-way. And traffic analytics tell us in real time if nobody’s interested in reading what we write.

The comment thread that follows does the rest. It changes how we write, I think.

19. The stable business model

The flip side of the huge barriers to entry was that as an employee you could be reasonably confident that if your employer had been in business for a while, they were going to stay in business.

Circulations were stable, and advertisers were loyal. You had what looked like a job for life.

20. Trust

While people would always joke about whether you were from The Sun, journalists were mostly respected and trusted, in a way they are perhaps not any longer. You’d be invited to come in to schools and give careers talks. A wedding photograph or 50th anniversary picture in the local paper would be treasured forever.

21. The time before email

Now it feels like email has been around forever. I reckon I started using it regularly in about 1996.

Of course it’s an amazing resource, but it’s made the relationship between PRs and journos an asymmetrical one. I miss the days when a PR’s pitch to a journo was one-on-one, not a single button to email hundreds of titles.

And it’s also a wonderful publishing distribution tool, and an underrated one at that.

22. When you needed a notepad to browse the Internet

There was a brief period between when we had the internet on our computers and when Google came along.

I used to tear articles about new websites out of newspapers and staple them into a notebook for future reference. That was my search engine.

I remember at about that time urging my publisher that we should buy the URL doctor.co.uk (it was the name of the magazine I worked on). He balked at the 50 quid price tag. The mag is no longer in business.

23. Before smartphones and tablets

Most of us as journos don’t, deep down, understand what mobile really means for us yet. The way we write, even for the web, isn’t that different to how we did it for print. We tend to consume and check our own words on desktops.

But a mobile browser behaves differently. For all the talk of “mobile first” publishing, not many of us are really dealing with it.

Yet tablet technology changes everything.

Last month we had a keynote speaker from BuzzFeed at our Mumbrella360 conference. On my iPad, I tracked his flight, watched it approach Sydney airport in real time, took a picture of it from my balcony coming in, and posted it to Twitter.

Looks like we’ve got a keynote. The dot on the horizon is BuzzFeed’s @keithrhernandez. Welcome to Sydney Keith #m360 pic.twitter.com/uiE0PUl2ja

— Tim Burrowes (@mumbrella) June 3, 2014

Most of those tools have been around for less time than Mumbrella, which isn’t even six years old yet.

24. Before video

We can all do live video now – any of us, at any time. All it takes is a webcam. It’s another game changer we haven’t fully understood yet. It’s happened so fast.

Four years ago, we live streamed the first Mumbrella Awards. We had to instal a special, dedicated fast upload connection. And it was still pretty dicy. Five years ago, last time I ruminated on this stuff, video wasn’t even on the radar for us.

Last week, I sat at my desk and streamed a chat with consumer psychologist Adam Ferrier about marketing science live to our home page.

And it was all completely routine.

25. The romance

But there is a romance about journalism that we are in danger of losing.

Unless you’ve phoned over a story right on deadline, headed back to the office and picked the paper off the press to see your front page byline, you may not know what I mean. I’m not sure those words mean quite the same when they’re on a computer screen.

Next

The retirement age is 70, and I’m coming up for 44. So I seem to be approaching the halfway point of my career. For all the scary things happening to the business models, it’s been an amazing time to be a journalist. The next quarter century is going to be mind-blowing. So long as I don’t get found out.

- Tim Burrowes is content director of Mumbrella

Linkedin

Linkedin

The brick phone! Great piece Tim. Yes, if only more journos would take an interest in how their story is playing with the audience – difficult with the workload now…

User ID not verified.

Tim,

Thank you for this. You have encapsulated better than I could and it was a nice trip down memory lane. When I left my first newspaper I asked if I could take the spike with me. I still have it somewhere.

I still use shorthand to this day and combined with the keyboard I can’t actually remember the last time I spent some time writing normally on paper.

Glad to see that you had the same experiences as myself with the snapper always dropping in those missed questions or saving your ass when you were just fresh.

I have to ask though. What was your first frontage headline? Do you remember it?

User ID not verified.

Brought back some good memories Tim. Agencies too were very different 25 and more years ago. Whilst there have been some huge advantages with changes and more fantastic tools to use, we seem to have lost some valuable inclusions along the way.

Agencies invested in training programs and their staff, mentors stretched, challenged, encouraged and often stopped you stuffing up and real career paths beyond 35 were possible.

Perhaps we have become overly self indulgent and obsessed about congratulating ourselves with numerous awards that other industries see as more than a little ridiculous. Being excessively busy and working towards burnout whilst sacrificing time with family and friends is worn as a badge of honour.

And sometimes we even lose sight of that our role is very simple. We aren’t creating world peace, feeding the hungry or curing diseases. We just sell more stuff and hopefully have some fun along the way.

User ID not verified.

Nice piece of fine nostalgic insight. That pic of you in the fireman’s helmet is hilarious.

User ID not verified.

There’s a lot I can relate to there. I started with a country newspaper in South Australia. I used a typewriter for the first six months before we moved to clunky green-screen word processors – that was in 1982. I recall attending rural shows, leaning against the car and balancing the typewriter on my knees so I could prepare the results for my paper and to phone through for the Advertiser. We had proof readers and paste-up artists back then as well.

User ID not verified.

Surely the biggest change in journalism in the last quarter of a century must be that there used to be jobs back then.

User ID not verified.

yep started in newspapers in 1981…in the advertising department. On the totem pole we were somewhere below the reel mounters on the presses. Senior management, editors, journos comps then everyone else was the way I remember it- and the comps would dispute journos being ahead of them. Everything was done by hand, layouts on paper, in pencil, so they could be changed at the editors whim, ad copy taken done over the phone, and recorded in a book. Cut out repeat ads, send them to the block room to dig out the old zinc, and then off to the comp room to be made up.

Despite the manual labour it was an intense but fun job, and you felt like you were part of something important. Still in it today, the sense of being part of something important may be diminished slightly, or maybe that’s just cynicism…

User ID not verified.

Outstanding piece.

User ID not verified.

Ah yes, the old days. Plus aggressive and abusive editors, luv’em.

In my first journo job the editor was the then legendary Red Harrison, former WW2 spitfire pilot or some such.

I proudly but tentatively slid my first ever story to him for his perusal and after a quick read he said, “This is shit.”

I slumped back across the newsroom thinking my career had ended before it even started. But Terry Conroy, the chief sub, aware of what was going on, mentored me as such by telling me I had the basis of a very good story but had ruined it by including smartarse “university paper” asides and comments.

All my supposed cleverness was excised and Conroy marched me back across the newsroom again to front Red.

He looked at me and then at Conroy and said to him, “I thought I said his story was shit.”

Conroy: “He’s rejigged it Red and I think it’s worth your time to look at it again.”

Red read it, and abruptly declared, “Okay, that’s the page 3 lead.”

He then looked at me and snarled, “Why did you waste my time by bringing me the shit version in the first place?”

Lesson learned.

User ID not verified.

Lovely piece Tim, remember that Nokia Brick and layers between writing and publication. Good to be reminded of the ridiculous hours too. And that nothing stays the same.

User ID not verified.

25 years? You haven’t aged a bit since that firey photo!

User ID not verified.

Very very interesting. I grew up near Aldershot and I remember the Aldershot News clearly. Sad to see that it’s gone. Thank you for the memories Tim.

User ID not verified.

AS a former journo for almost 30 years, I thought your piece was excellent Tim, on every point. And the last one is the saddest. That adrenalin of an exclusive, byline and front page is the one of best rushes you could get. I don’t sense it’s like that anymore for all the reasons you outlined.

Being a bit older than you (not much!) can I note a few things: while working for Variety in Sydney we had to courier our copy to NY every Thursday, with a telex as a back up for urgent stories (or by phone). The huge fax we received in 1985 replaced that. We had to have an hour long tutorial.

I ditched the typewriter in 1986 or so for my first laptop (Tandy) with 12KB memory and a screen about 25cms long and 10 wide. The first email then happened the next year via MCI and a modem you had to stick on the headset. Then came the first mobile in 1989 or 1990. It cost $1000.

And one thing you didn’t mention was the UTTER importance of your tatty contact book (I once had to get mine express mailed to me after leaving it in a NZ hotel) with its precious direct and home numbers.

Who would’ve thought back then a mobile phone is all a journalist needs now?

User ID not verified.

Had a similar experience as a copywriter.My first boss was an old-school guy who hid his kind heart under a barrage of insults and speculations about my low intellect while teaching me the countless errors of my ways. Talk about unqualified knucklehead learning on the job!

He was so ferocious (it seemed) that I would only leave copy on his desk when he went out and or to lunch. Then one day he said to me: ‘Look son, if you’re going to write this awful #@#&!!ing crap, at least be man enough to bring it to me in person!’

He is long gone now. I’m glad he’s no here to see what has become of our industry.

User ID not verified.

congratulations on what you’ve achieved with the burgeoning Mumbrella empire Tim. I think you’ve found your niche. To hell with A levels.

User ID not verified.

Oops! I meant ‘not here’.

User ID not verified.

I’m 69 (a young 69 I hasten to add) and it mirrors my recollections. A copy boy in Adelaide, a cadet journalist in SA on a regional newspaper, then the ABC and a year working in North Herts on a paper that’s since gone to newspaper heaven. The same experiences, dial phones, snappers in the UK but photographers and cameramen (one woman) in Australia, smoke filled subs’ room, a chief reporter who knew everything and, as a copy boy, delivering dim sims to the subs on a Saturday night only to see the leftovers pelted around the room and narrowly missing the beer bottles and flagons of claret…old reporters who wore fedora hats inside, men who knew every word in the dictionary, chiefs of staff who told you the difference between effect and affect, and an editor who had lunch outside every day and came back at the end of the day with a red face. All changed now, but it for the better I fear. Still. That’s progress. I think.

User ID not verified.

Could I also point out – the picturegram machine – for sending photos down a telephone line. Truly ‘mazing at the time. Kinda like a fax, with the black and white photo curled around a rotating drum. A thin stream of light detected the image and sent it to another similar machine in far away places. Didn’t think to call it photo sharing at the time…

User ID not verified.

But more importantly, did you ever go to the artificial ski slope in Aldershot? Great memories of broken fingers and sore heads there.

PS Enjoyable nostalgia – thanks.

User ID not verified.

Thanks for clearing that up AdGrunt – I thought it was a young Benny Hill in the fireman’s helmet.

User ID not verified.

Good yarn. Having once accidentally sat on one of those metal spikes (for spiked copy) when taking a break on the corner of a desk quite a few decades back, it’s one aspect of old-style journalism I was pleased to see vanish. Hard to get spiked with a computer (though we’re probably just being nuked instead).

User ID not verified.

Great piece Tim. I came up through an ad sales dept in the same period – I can still remember the nicotine stained ceilings, shite coffee and the utter disgust my former editors had for suggestions from overly cocky junior sales grunts! Brilliant days.

User ID not verified.

Great piece. I started almost 30 years ago too. Typewriters, newspaper office library, riding in cop cars for the night with no-one from PR in sight, not knowing who was in the editorial room because of the smoke from the cigarettes, Friday afternoons at the pub, great contact book, ducking copy thrown at my head by my first editor because it was “shit”, never being asked to take a photo because I was a reporter and just some of the best belly laughs of my life. Have just started my own publication – The Local – and it’s all fun and real journalism again. Back to basics. tlnews.com.au Journalist’s dream job!

User ID not verified.

If you want to know about how it used to be, try reading Mumbrella (or anything else for that matter) via the Web at 256kbps because its school holidays and the kids have used up your 200GB allowance and you still have three days to go in the month!

User ID not verified.

Tim, I loved your piece. It took me back 30 years, when I started in journalism. Haha, I remember the spike, the manual typewriter, the fax. I also remember the telex machine! And that’s not to mention the press releases which were posted. Yes, young PR people, snail mail. So it took days for a release to hit a journo’s desk. I also remember the LONG LONG lunches and smoke filled pubs we frequented after (and during) work.

Tim, your story made me sad and nostalgic. When I started with Fairfax, we had a sensational cadet training program and had some excellent journalists mentoring us. How that has changed… and not for the best. We also had some outstanding sub-editors. Ones who wouldn’t let a mistake-laden front cover hit the newsstands.

No I’m in PR (yep jumped to the so-called ‘dark side’ back in the 90s), and I agree wholeheartedly with all your comments about the rate of change in how we do things (technology is an amazing thing).

The last couple of years have seen enormous change in journalism and PR. I feel sorry for those young kids with stars in their eyes hoping to become a journo. Because it sure as hell aint so easy any more.

Thanks for taking us down memory lane. It reminded me of my first job, before Fairfax, at the National Constructor, owned by Sir Asher Joel, one of the gentleman publishers way back when. Sometimes I wish we were still in the good old times 😉

User ID not verified.

Still have a rather too vivid memory of a demonstrative journo slamming his arm down on the subs desk at Cumberland Newspapers – right through a letter spike.

User ID not verified.

Great Piece, I love the history of most things, this is especially interesting.

I remember a chief announcer complaining about the insertion of the word “tragic” in copy reporting a traffic accident. Seems funny these days, where traffic accidents are often treated like an opportunity to write and voice a dramatic monologue.

User ID not verified.

I started to tear up Tim.

I could hear the police scanner bleeping and cackling. I could see the white Holden sedan and driver waiting downstairs to speed us to the news event. I could hear the “sssshhhh” from the back seat as the photographer opened his first tinnie of Reschs for the day — at 6.15am. Most of all, I could SMELL the print from that monolithic building in Jones Street, Broadway. I loved that place.

Thank you for giving me a reason to remember.

You nailed it with 1, 2, 12 and 14. Fairfax wouldn’t grade you unless you had 100 words a minute shorthand. Your copy would go past 9 — NINE — sets of eyes before it was printed. You learnt from men (it was the 80s!) who had forgotten more about journalism than what you thought you would ever know.

I wanted to take a spike too when I left for advertising but was told I couldn’t. In the best traditions of the tabloid reporters who had gone before me, I did anyway.

User ID not verified.

Crikey, you’re memory is impressive. I had completely forgotten about the spikes but, now you mention it, I do recall having to clear the darn thing out every so often and agonising over what I dared to throw away. Even in these tech-friendly days, I still store old notebooks and, like you, use my shorthand regularly, much to the consternation of many who see it. A lovely look back to a different time and, yes, I also think the saddest loss is that ‘hold the front page’ moment and then seeing your byline there in print. Lovely piece Tim, thanks for the memories:)

User ID not verified.

Tim, as that Chief Reporter, you make me feel about 900 years old, but I am actually only six years older than you!

I look at the stickers on the windows every time I drive past Penmark House.

I would add that as a cub reporter, you were incredibly hard working – it was difficult to get you to stop – so you were always going to do well! And, although I haven’t seen her for four or five years, Shelagh Stephenson always mentioned you when I spoke to her.

Sadly today, the Aldershot News has one reporter and the Farnborough News has one. The circulation is about a fifth of what it was in ‘our day’….

User ID not verified.

Do any of you former or current journos in the UK remember or know of Home Counties Newspapers which included The Luton News, North Herts

Pictorial, Stevenage Pictorial etc? Wonder what happened to them. I spotted a photo of the old office in Hitchin (several hundred years old) and it’s now a dry cleaners.

User ID not verified.

My first job was at triweekly country paper and second at a suburban weekly both very similar to the one you describe in this article. I started in 1991, and everything you wrote brought back huge waves if nostalgia. I later moved on to metro Sundays, dailies and national dailies, and my current job as a “new media editor” for a news website, but there was nothing like the pure journalism of my first few jobs. Cranky subs, spikes, fax machines, phone interviews and all. No doubt much of what has changed is for the better, but I feel privileged to have been part of that final golden era for newspaper journalism. Thanks for sharing.

User ID not verified.

Having started in the same newsroom as Tim about two weeks earlier I can vouch for (almost) every word. No mention though of the boozy lunches that stretched for hours, although Tim’s work ethic, fuelled by Diet Coke if I recall, put the rest of us to shame.

You’re right Tim that so much has changed. I now work as comms manager at a UK hospital that serves the same people we used to write for at the Aldershot News and our patients’ magazine has a higher circulation that the newspaper group we used to write for. So much has been lost but I’m pretty optimistic about the future of journalism, albeit very different from the one we knew when we worked together at Penmark House. Happy days, great article!

User ID not verified.

Nice yarn!

User ID not verified.

Wow, you brought back a few memories there (and a few former colleagues in the comments!) I’d forgotten about those spikes too … and now I’m remembering spiking my hand on several occasions after getting over enthusiastic with it.

Great piece Tim, I really enjoyed the memories.

User ID not verified.

Tim – great piece – I knew you as one of the Two Tims of Campaign in the sandpit circa 2005, and clearly you have done better things!

A great look at the industry, that I only glimpsed through work experience slots in the early 90s. I don’t think most of those lessons have been passed down, and we are poorer for it today.

(but I don’t believe you learnt on a typewriter – even my fancy journalism college had greenscreen word processors (locoscript?) in 1991 😉

User ID not verified.

I started learning shorthand in the early 1990s – but never quite finished the course. I can write in shorthand, but never quite mastered the art of being able to read what I had written! However, it made such an impression on me that I still regularly write shorthand in my head… Since RSI has kicked in, I am much more of a fan of dictation software. A lifesaver!

Loved reading your article. Yours, dictated in Kampala, Uganda…

User ID not verified.

I remember that your story was ‘spiked’ if it wasn’t to be used – a term still used today.

As a cadet I could earn a grade (and pay) rise by achieving certain speeds in shorthand … I got fast, quick.

Those layers are such a loss, for the reader, and for young journos who don’t have as much access these days to the ‘wisdom of the elders’. Those elders who are left don’t have time to mentor.

You’ve told my/our story well. Thanks for the memories.

User ID not verified.

What a fab walk down memory lane! It mirrored my younger days as an spotty-faced trainee reporter on the now defunct Oldbury Weekly News just north of Birmingham in the UK in the early 1960s and the still thriving Express and Star until I moved to Oz in the late 80s. I was known as Dennis Poxon in those days but have now changed my name. Oh happy times. Still got printers ink in my blood, hence Caravanning News. No one to check my copy these days … It’s a one-man band. Mind you, I must admit to cringing sometimes when I read it after it’s been on the web for a few days. Again, thanks for the nostalgia.

User ID not verified.

I loved this story. Completely resonated with me. In appreciation of your writing Tim and with a curtsy to grand times. Thank you

User ID not verified.

I remember that separation between editorial and advertising really well. When I started as a journo editors could not be bullied into running stories just because a company advertised with them. One of the mags I wrote for had a motto of “Tell it like it is” and they did.

Then gradually it became tell it like it is (but don’t offend the advertisers)

Tell it like it is (but make sure that it is positive for the advertisers)

Until it because – Tell it like the advertisers want it to be

At that point, I realised that I had essentially become a PR who was just driving a crappier car than my agency colleagues.

🙁

User ID not verified.

I too learned the journalism trade by writing stories one par at a time on slips of paper on a manual typewriter.

Years later, I read a biography of Raymond Chandler — you know, the author of the Big Sleep and other noir crime novels.

The biographer commented on his ‘unique’ writing technique. To the biographer’s astonishment, Chandler wrote his novels one par at a time on slips of paper on a manual typewriter.

But of course Chandler wasn’t unique. Although he was an unemployed oil executive when he started writing, his early training was in newspapers.

He wrote his novels the same way he was taught to write news stories — and in my view it shows in the tightness of his prose.

User ID not verified.

I started out as a newsltd copy kid at holt street in 1995. No-one called my name, just yelled “copy” when they needed lunch picked up, coffee or anything else. Lazy journos. But on the late shift, the call “copy” would send me running to the composition room to pick up a bromide print of a page and then run it to the subs night desk for a check before it was sent to te presses. I loved it. Imbued me with a tactile sense of news.

User ID not verified.

I, too, am a few months shy of 44 and started my first newspaper gig on The Border Mail in 1992. I recall my first day interviewing Craig Mclaclan (former Neighbours actor and, ahem, pop star). On my second day I went to court with the grumpy court reporter and listened to a tail of woe from a local marijuana grower. I knew I’d found my niche. A little over a year later I was subbing on Fleet Street and getting 125 quid for a six hour shift. Do Fleet St subs even get that nowadays? Thanks for the piece. It brought back many memories.

User ID not verified.

Hi Tim

You have really struck a chord with this one, Tim ! At Cumberland, cadets were either ‘horse’ (copy carrier) or Fred. Job promotion was a phone call from the editor in chief’s secretary telling you to go his office , followed by : “Okay Fred, you start work at Penrith on Monday as reporter. Keep up the good work”. You earned your real name once you showed you could do the job. I remember attending a cadet lecture at News Ltd in town and told by then Daily Mirror editor tips on doing “death knocks” ,ie interviewing family of usually young people who had died in traffic accidents, a Mirror staple. His tip for early morning dks- knock on door, pick up milk bottles (remember them), and when the mum/dad answered the door, hand them the milk bottles and start talking as you walk in, to stop them slamming the door in your face !!!! Questionable ethics ( I came away wondering if I was in right game) …. but in those days, the Sun was breathing down your neck – every story counted.

User ID not verified.

I had two paper rounds as a kid in the UK, one morning and one evening. £15 per week. Rain or snow I would be out before and after school delivery the news. A Doberman chased me once and wanted to eat me. The police greeted me at the front door of a house, the owner was dead in the back garden. One morning in a street with steep driveways I had to crawl as the ice was so slippery. My Sunday morning round destroyed my shoulder, heavy broadsheets and supplements; the bike crossbar would carry my day glo orange paper bag. I grew up with papers, the ink stained my hands. The smell of the print was strangely nice. It will be a shame to see them go.

User ID not verified.

Delivering*

User ID not verified.

Fabulous piece, Tim.

I can best you in terms of years of service – by 16 – but most, if not all, of the points you make resonate with me.

Kudos to you.

Chris

PS Sid Bonkers points out that it is try to not try and…

User ID not verified.

PS Did you spot the unnecessary q at the end of my name?

Sid Bonkers put it there, I swear.

User ID not verified.

In Australia, editorial traditionally ended up with the castoff typewriters from all the other departments, which mean that with seniority came the claim to the best of a bad lot.

Sticky or missing keys and dodgy ribbon rollers were the lot of cadets.

And all that carbon papery, often so that our bosses could on-sell the fruits of our labours to radio and TV newsrooms and wire services!

Not so many years back, the workplace health and safety narks stormed through newsrooms removing the spikes.

And, god rot them, nobody in authority in editorial told them to piss off.

A sign of our diminishing role in age when even advertising shonks are allowed on the editorial floor.

User ID not verified.

Hi Tim,

I didn’t have the opportunity to work with you, but I did work at Penmark House a few years later with James. I was came into journalism right on the edge of the new media revolution and looked on as many of the ‘Old Guard’ sadly received their marching orders when a new editor came in with a new computer system and the Internet. I feel privileged to have learned many invaluable lessons from the staff there – including the infamous Glaswegian news editor, who nearly blew a gasket at me on deadline once – but that was my rite of passage, could I hack it? The the practices you speak of were very good ones. Let’s hope as digital pans out some of of those old traditions filter their way down.

Sara Mills (Aldershot News, circa 1998)

User ID not verified.

GLASWEGIAN? The nearest I get to Glasgow is when the missus bullies me into driving there for the Christmas shopping! Invernessian young man, the city in which I am now living in brooding retirement. Yes Tim, I WAS that grumpy old news ed’ and I remember your interview as though it were yesterday. Like most aspiring whiippersnappers who stepped through the doors of Penmark House – I seem to recall we ‘senior men’ referred to it as ‘the banana warehouse’ – you appeared nervous and uncertain. However, to borrow a line from Abba, we ‘took a chance on you’ and it worked out just fine. Hard-working, dedicated, keen – take your pick of all the popular buzzwords. I’m afraid that your adventures in the world of what I still refer to as ‘new technology’ are way above my head, but I am delighted with your success. The ‘old Aldershot News’? Ah yes, we knew the days.

Ian Barron (News Ed’ – Retired!)

User ID not verified.

Yes! So well written – and I remember so many of these. I had a short experience of typewriters, by the skin of my teeth. I did a BA in journalism, at the first university to teach digital publishing back in the day. But one of my first work experience placements was at the Manly Daily in Sydney, where I had to do the folio copies, complete with spike stick. So glad I got to experience that. Later, freelancing in Cairns, I got to phone in copy to the Courier/Sunday Mail and overseas … some less urgent magazine stories were sent by fax and post prior to email. Sometimes the best stories came from the casual wrap up chat at the end – you don’t get that with emails. And young journos (and subs) certainly don’t get the mentoring they got back in the day. I’m hoping that eventually all that was old will become new again – well, at least the best of it will. Some of those traditions need to stay alive. A few may best be left in the archives.

User ID not verified.

Fabulous read! I, too, have notched 25 years as a journo, though that includes dipping into PR/media releases/corporate work, but at the end of the day for me it’s all about writing and reporting from a different perspective … ok, PR’s more about one perspective.

User ID not verified.

a key point: “The single most significant change for journalists is the ability for anyone to get their story out” -Tim Burrowes.

“To be independent then, you’d need to be able to afford to print your own mag or newspaper. Starting on your own would probably mean putting your house on the line. Now, of course, anybody can start a blog, and if that’s too much trouble, share on Twitter.”

User ID not verified.

Love this piece, Tim, so many things I could identify with – and a great kicker in the unspoken reality that 25 years ago, no-one would have written a list-based article with the title you use!

I was taught (at uni) how to file on a manual typewriter para by para, but there were already computers at the Spencer St soviet by the time I started.

Unfortunately, the computers were clunky great things on lazy Susans, so one computer could be shared between two reporters who invariably both needed it at the same time.

You seem to have missed out on the era of pagers. Fond memories of being buzzed and dashing to the nearest phone box to call the office…

The instant feedback loop of the internet is a mixed blessing. The audience is not always most interested in the most important news of the day, to say the least.

It also seems to be increasingly acceptable to report speculation around something as newsworthy in the “quality” “press” viz. Kate’s rumoured pregancy.

User ID not verified.

I loved this too Tim, working in Wairoa, northern Hawkes Bay in the mid 1980s I used to have to drive my copy to the tiny one pilot plane each night at the edge of town airfield to be flown to Napier for processing, the morning police round was phoned to a copy typist Carol, such a great adventure you are not aware you are having til later. Horrid being admoished from a distance or summoned to the head office though. A long funeral drive in the company car.

User ID not verified.

“I DONT GIVE A SH*T HOW MUCH THEY SPEND….F*CK OFF BACK TO ADVERTISING YOU C*NT!!”

Old school editors, gotta love em.

User ID not verified.

I know if o said carbon copy to most reporters today I would have to explain what it meant 🙂

User ID not verified.

@Rae

Or they would nod sagely and talk about global warming 🙂

User ID not verified.