Crisis? What crisis? Why recognition is critical

Denial is the enemy of crisis management, but that doesn’t stop some CEOs sticking their heads firmly in the sand when a crisis comes to call, argues Tony Jaques.

Every organisation should know when it’s facing a crisis. Sadly, it just ain’t so, and that can be a major problem.

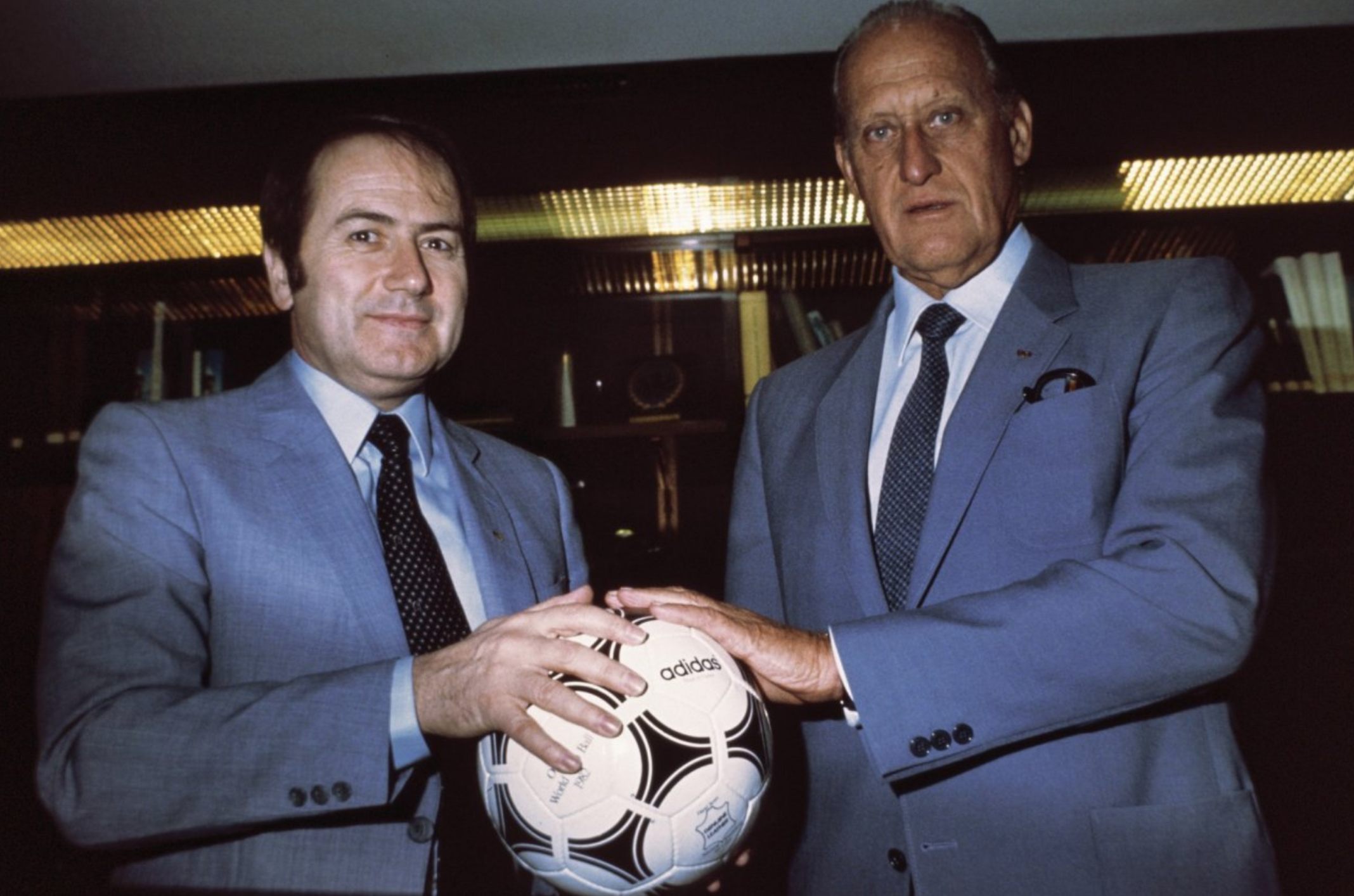

With the football World Cup about to begin, consider the notorious case of former FIFA President Sepp Blatter. When football’s governing body was accused of corruption way back in 2011, he famously responded: “Crisis? What is a crisis? We are not in a crisis, we are only in some difficulties and these difficulties will be solved inside our family.” Four years later, facing renewed allegations, Blatter was finally forced to resign.

Sepp Blatter in 1982 (L) Source: Wikipedia

Recognising key or impending crises is very important for small businesses and the non-profit / religious / community sector. The one that most of us may remember is the child sexual abuse that had taken place within the Catholic Church and organisations that it controlled. Then there is also the haircut saga that recently beset Trinity Grammar where there was loss of confidence in the leadership of that school.

Here, being able to identify that the organisation is in crisis and take appropriate action is important for all stakeholders especially if it is the kind of crisis referred to in this article as a “creeping crisis”.