The only role less meaningful than being Australia’s media minister is Veep

When it comes to media policy, Australia’s major parties are too scared of the big players to break the status quo – and that’s unlikely to change after the election

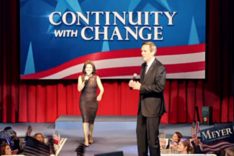

One of the most entertaining themes in HBO’s brilliant corridors-of-power comedy Veep is that being Vice President of the United States is the most unsatisfying job in the world.

Each time that the president of the day tells a new would-be Veep about how they’re going to be a big part of the team, be consulted and make a real difference, both parties know it’s a lie. As Selina Meyer puts it, “I’d rather be shot in the fucking face.”

The same goes for the role of Australia’s media minister.

With too much politically dangerous real estate under their feet, a successful media minister is an inactive media minister. If ever there were a role offering prestige without power, this is it.

The risk of annoying powerful media owners is cynically almost always allowed to outweigh the need for good public policy.

And if there is real policy to be done in the space, it’s so politically sensitive, the Prime Minister of the day will make the big calls anyway.

As a result, the inaction on media regulation is all about politics, and on the rare occasions that there is activity, that’s about politics too.

Small wonder then that we haven’t had any real changes to media law for more than a decade, under either Labor or the Coalition.

The pattern, particularly around media ownership laws, is instead one where the media minister arrives and makes some early noise about reform.

The minister then begins to enjoy a honeymoon political period. The big media outlets go easy in their reporting on the minister for as long as the possibility of reform sits there.

Not being stupid, the media minister is in no hurry to disrupt this helpful status quo as months eventually become years. Finally, when the situation becomes too awkward to bear (or enough implacable media enemies have been made), the minister takes a new policy to the PM of the day, and perhaps even to the cabinet.

Usually there’s a further delay at this point as each cabinet minister views the policy through the lens of their own individual local situation. Regional members might worry more about beefing up local content to placate their local constituents while not annoying regional media players; the city members will worry more about upsetting the big guns.

Eventually, usually half-heartedly, new policy is outlined, and legislation is drafted. It then of course fails to sail through the legislative process.

By which point enough time has passed that a party leader gets rolled, or the election gets called and the whole thing gets put on ice once again.

So the last time we had any serious reform of the media ownership laws was during Helen Coonan’s days as minister, towards the end of the Howard government more than a decade ago.

And even that didn’t set up Australia for the digital future that was already on the way.

They changed the ownership rules away from Paul Keating’s previous “queen of the screen or prince of print” choice for media owners, to allowing the ownership of two-out-of-three media in any given location. So you can’t control a TV network, radio station and newspaper in the same city.

The other key element of the current media ownership rules being that TV licence owners can’t reach more than 75% of the population. Which is why we see Nine, Ten and Seven doing their complicated affiliate dances with regional players WIN, Southern Cross Austereo, Prime et al.

The best hope for wider reform in the last decade came through Labor’s Stephen Conroy, who had nearly six years in the gig, from 2007 to 2013.

He was also the only media minister during the decade just gone to have an actual vision for something. In his case, it was the National Broadband Network. And of course, we’ll know never know whether his fibre-to-the-premise vision for the NBN would have been as transformative for Australia as supports of the idea though.

But unfortunately, as often happens to enemies of News Corp when they are prodded for long enough, he went mad. And went to war on the media.

He commissioned Ray Finkelstein’s inquiry into the regulation of the media. And while Finkelstein and friends came up with a great summary of the problems faced by the media, its solutions around regulating the press were so unworkable and anti-democratic, it never stood a chance of getting up.

Which meant that the baton passed to Conroy’s former shadow, Malcolm Turnbull, who did not have a big idea for the media, despite being involved in it for most of his career.

Back when he was shadow minister, I asked him whether he had a big idea for media regulation. You can see his lacklustre answer below, just after the 10 minute mark.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2XzYYs3G5nw

Encouraging more competition, was all he really was able to say.

And of course, his time as both shadow and media minister had even more parallels, with him parked in the role by his biggest rival Tony Abbott, who has rolled him as party leader.

So Turnbull – probably the cleverest, most able, most media-savvy person ever to be media minister – achieved exactly nothing in the role. Instead, his entire focus was on dialling back Conroy’s vision of the NBN to something cheaper and based more on copper and less on fibre.

Naively, for his first few months, I was convinced that the real Malcolm would emerge and that he was playing a role, delivering the rhetoric Abbott was demanding while still quietly working towards a better outcome.

Ad then he became Prime Minister, which reset the media reform debate yet again.

In came Mitch Fifield as media minister.

I haven’t met him, but Fifield seems nice enough but not at all inspiring. A rather good small target as media minister, I guess.

As part of the election hustings, we invited him to debate media policy with his labor shadow Jason Clare in front of the industry at Mumbrella360 earlier this month.

Clare said yes straight away. Fifield’s people prevaricated forever and eventually said no.

Prior to Turnbull’s elevation to PM ,the media ownership stuff had by now been languishing in the drawer thanks to Turnbull’s claim that he was leaving it to the industry to achieve consensus.

Which was about when I stopped believing. Good policy comes from government. Not least because they’re the ones with a mandate to represent the interests of the public, not by the industry players coming to a cosy consensus.

Eventually of course, the proposed ownership reforms did go briefly before Parliament. Then Turnbull called the double dissolution and that was that.

If he wins, and Fifield stays in place, then there’s a small chance that the changes will finally take place after the election. Otherwise, there’ll be yet another delay.

But even so, I see no prospect on the horizon of a media minister with any sort of wider vision.

We know seems stuck with a media portfolio that consists entirely of deciding who can own what and whether the NBN will be made of old pipe cleaners or carbon nanotubes.

Any wider vision just seems not to be required.

Earlier this year, the Australian Financial Review briefly floated the question of whether the bluff should be called on the special pleading from the big TV companies that they should get a discount on the licence fees they pay to use the public airwaves.

Instead, why not do what Margaret Thatcher did in the UK, and test the market? It’s worked very well when auctioning off the airwaves to the telcos.

So why not invite an open bidding process. As incumbents, the networks would have a big advantage, but we’d find out what the airwaves are really worth to them.

But instead, we’ll go on having the same argument about the NBN.

Fifield did eventually front up Jason Clare on the ABC just over a week ago. But the only thing they discussed was the NBN.

Certainly its fair to say that wider media policy has in no way been an election issue.

In the most recent episode of Veep, President Meyer obsessed about her legacy.

For Australia’s small target media ministers, leaving a legacy is not something they’ll need to worry about.

At least you got an answer from Fifield’s people.

The NBN is a classic example of incredible vision with questionable costs that was then completely bastardised for political reasons.

If the Liberal party were responsible for building the Sydney Harbour Bridge today it would be single lanes each way.

This article is rubbish.

First it’s the communication minister, not the media minister.

Second, governments aren’t afraid of media players, they can do what ever they want to legislation provided they find the right support and any proposed reforms find their way through parliament and achieve royal ascent. They need approval from parliament not media owners. Any failings of previous media reform has been to due the lack of bipartisan support in parliament, albeit with pressure from the press.

Finally, this article suggests that the current Bill put forth to parliament by Mitch Fifield is unlikely to pass. Not true. The current has been referred to a Senate Committee that has had submissions from all key societal stakeholders and overall the findings revealed a strong level of bipartisan support, community support, academic supports, ACCC support and support from media owners. Small concerns do exist and most media owner feel they don’t go far enough by not tackling anti-siphoning laws. Many welcome the laws as it will help them achieve scale and combat offshore threats who face no regulation. It is very likely this bill will pass, therefore your article is moot.

Hi Jack,

The role of what I’ve generically called media minister (lower case), has had a number of different titles in the time period I’m talking about. Mitch Fifield is the Minister for Communications and Minister for the Arts, Stephen Conroy was Minister for Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy.

And as to whether the bill passes, you may be missing my main point which is that it’s once again been pushed back until after an election, where it once again becomes at the mercy of (potentially) yet another media minster…

Cheers,

Tim – Mumbrella