What’s the point of something like Mumbrella360, anyway?

Last year, a single-panel cartoon sold at auction for $175,000 – the highest amount paid for such an artefact in the history of all histories.

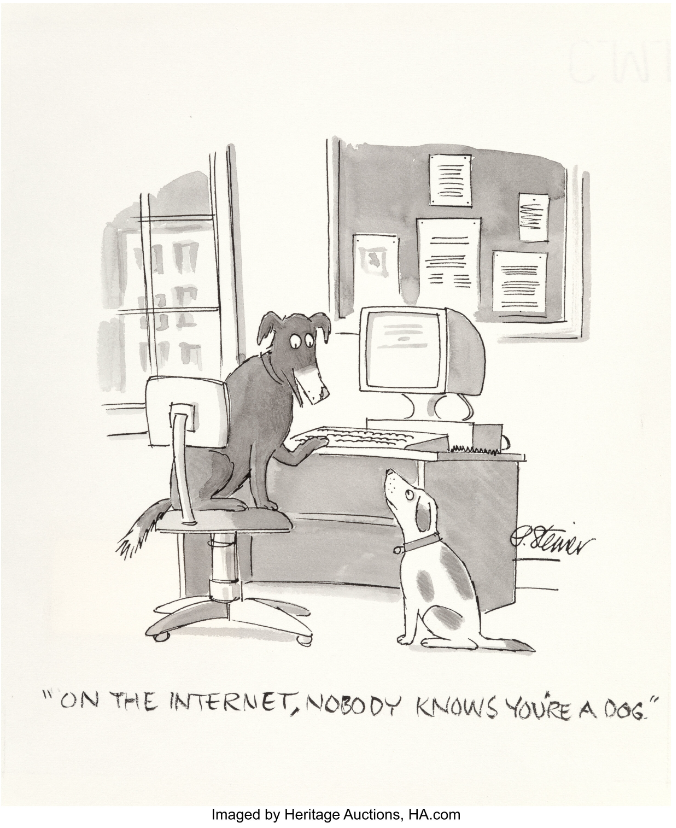

Naturally, you’d assume it was an old DC Comics frame, or a Snoopy scribble – but it was actually a black-and-white cartoon published in The New Yorker in 1993, titled ‘On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog’ – which distilled the essential truth of online life.

In 1993, the internet was so new that the cartoon’s prescient layers – i.e. the horrors it tried to warn us about – cannot have been intentional, and indeed were not. Peter Stiener recently told Heritage Auctions, who sold the original, his cartoon “wasn’t about the internet at all. It was about my sense that I’m getting away with something”.