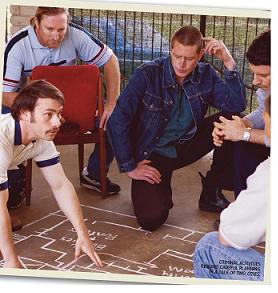

On Location: Underbelly, A Tale of Two Cities

With the success of Underbelly and a bottomless source of true crime stories, a second series was inevitable. Peter Galvin visited the set in an Encore exclusive.

With the success of Underbelly and a bottomless source of true crime stories, a second series was inevitable. Peter Galvin visited the set in an Encore exclusive.

Launched at the beginning of 2008 ratings season with a massive and expensive publicity push by the Nine Network, Underbelly became, says its makers, one of the most successful TV series ever produced in Australia. It’s not just the high ratings it brought for the Nine Network; the series has been a DVD blockbuster for Roadshow Entertainment selling more than 350,000 units.

“We’ve broken all retail records, and though we don’t have numbers on rentals, we understand it’s done big business there too,” says Screentime’s executive director Bob Campbell. The show, budgeted at $11-13million, has also sold extremely well into foreign territories.

The network began discussions with Screentime’s Greg Haddrick and executive producer Des Monaghan (Screentime) about a follow up season, soon after Underbelly finished its run. By mid-year Haddrick says, he had begun work with Felicity Packard and Peter Gawler, season one’s writers, outlining and scripting, with a forth writer, Kris Mrksa (Carla Cametti PD) joining the team for season two.

The first series was based on the book Leadbelly, by true crime writers Andrew Rule and John Silvester; a dramatic interpretation of the notorious Melbourne gang war of the 1990s. The new series, which began shooting on October 15 in Sydney, is set twenty years earlier, in the late 70s.

When Encore visited the set in December Haddrick, who is coproducing the show once more with Brenda Pam, explained that the this season is neither a sequel nor a prequel to the events and plotting of season 1. In fact, the Underbelly title is more like a branding or franchise, or perhaps a genre: “The aim is to create the same tone and the same style, [and to achieve that] we’ve applied the same process – all four writers were involved in the outlining and planning, and we all read each of the drafts as they came through,” he said. “When you think of Underbelly, you think of characters like Roberta, Alphonse and Carl and Jason, and we are not bringing them back and nor are we trying to find others like them.”

The key point of distinction between the seasons is in the title: “This is not Underbelly 2 at all…it is called: Underbelly, A Tale of Two Cities.” This refers to a rivalry between crime syndicates and individuals based in Sydney and Melbourne, and the tussle over control of rug trafficking in Australia – which by the mid 70s had taken precedence as the key ‘earner’ in the criminal milieu over “old style” rackets like prostitution, stand-over and gambling. Besides the strong violence and graphic sex, Haddrick says there are thematic links between the two seasons. “We deal with police corruption here, in a way that season one didn’t.” Real life characters and events are once again central to the on-screen action, with the relationship – some would say “mateship” – of two major figures from the country’s crime history dominating the narrative: alleged crime boss Robert Trimbole (Roy Billing) and convicted murderer Terry Clark (Matt Netwon). Known as Mr. Asia, New Zealandborn Clark controlled a syndicate responsible for importing heroin into Australia, NZ, and Britain, using a large ensemble of attractive women as couriers. Clark was said to have made a billion dollars from the enterprise.

ILLEGAL STORY, LEGAL PRODUCTION