How Big Brother rose like Lazarus

With 300 crew members, 42 cameras and almost 90 hours of television broadcast each series, there is no TV production quite like Big Brother. Encore managing editor Brooke Hemphill visited the set of the revived reality show to see how it is put together and found the training ground for Australia’s television industry.

With 300 crew members, 42 cameras and almost 90 hours of television broadcast each series, there is no TV production quite like Big Brother. Encore managing editor Brooke Hemphill visited the set of the revived reality show to see how it is put together and found the training ground for Australia’s television industry.

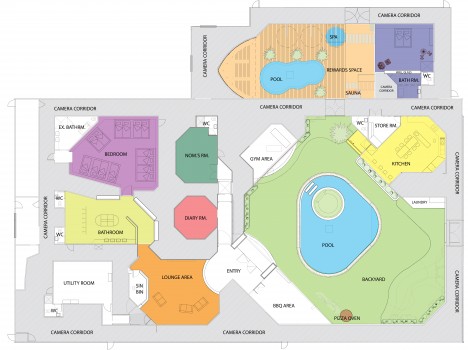

Down the dark corridor, lit only by red strip lighting on the floor, thick black curtains cover one-way mirrors. Like a sex peep show, unidentifiable silhouettes peer through gaps in the curtains. “Shhhh. The housemates are over here,” a voice whispers shining a torch in Encore’s direction. We’re in the camera space of the Big Brother house, where up to five camera crew are on shift staffing the 10 fixed cameras rationed between the various rooms. It’s a maze of corridors populated only by the camera team, who work eight hour shifts, and the occasional sticky-beaking reporter.

The housemates are in the purple bedroom and, if not for the mirrored glass, you could reach out and touch them. It’s a rather disconcerting feeling to see people lying in bed or taking a shower as two of the housemates are doing further along the corridor where we pull back the curtains to reveal plenty of naked flesh. This element of voyeurism is at the heart of Big Brother, a reality franchise created by Dutch production company Endemol in the late ‘90s that has since aired in 78 countries. For those unfamiliar with the program, it hinges on a simple premise. For three months, a bunch of strangers are locked away from the outside world with their every move being watched. Each week they complete tasks and are rewarded, or punished, based on how they fare. They nominate their fellow contestants and the public then decides who will leave at the weekly evictions by voting to save their favourites.

A local version produced by Southern Star Entertainment first hit our screens in 2001 on the Ten network. It lasted eight series before audience erosion resulted in a resting of the format in 2008. Mid 2011, then Southern Star CEO Rory Callaghan raised the idea of a revival with network CEOs. He asked Howard Parker to draw up a potential budget.

“I did 50 versions before I got a budget that I was happy with and that we thought we could deliver with the network,” says Parker, the show’s production executive. “I’ve never told anyone the budget. In comparison to previous years, it’s not dissimilar. It’s a very expensive show but when you amortise that cost into the hours, then it’s not necessarily as expensive as a lot of competing programs. Don’t forget, we’re due to make about 84 to 86 hours of this series.”

Those initial conversations with the networks came down to a bidding war between Nine and Ten. In September 2011, Nine announced the series would return in 2012. And the Big Brother machine that had been powered down for three years started to gear up.

“Who knew it was going to rise like Lazarus and go again?” asks Parker.

The rebuild

During the show’s previous run, the Queensland set remained intact between production periods and became an attraction for theme park Dreamworld. But in the three years of the show being off air, the house was stripped back to its foundations. This year, it took three months to design and 18 weeks to build under the watchful eye of production designer Rodney Brunsdon. “The house has become a major feature for the Australian audience saying ‘yes, alright, there will be a bunch of new housemates but what does the house look like?’ And that’s a fascination in its own right,” says Parker.

After the reveal of the house, the attention turns to its inhabitants. This year more than 20,000 people were seen during the casting process. Potential housemates faced an exhausting series of tests and games overseen by producers and psychologists. Karen Dewey, head of reality and factual at Nine, was heavily involved in the process.

She says: “In a room full of 100 people that want to be on a reality television show, all of the housemates stood out. They either stood out because they were quieter than everyone else, they were more certain of themselves, they were funnier or they were louder.”

Executive producer Chris Blackburn says: “I call it the dialogue test. You cast for people that can talk. Sometimes someone gets through who shouldn’t have passed the dialogue test and isn’t very good in the house.”

This year, 14 contestants entered the house, including two ‘intruders’ who came in midway through the show’s run. Eventually, just one will remain and take home a prize of $250,000. In the meantime, they are given a modest allowance while in the house to help with financial commitments for the life they have left behind.

In past years, contestants have managed to parlay their popularity with the public into ongoing work in the media. The most notable including Blair McDonough, who used the show to launch his acting career, Ryan Fitzgerald, the Fitzy in Fitzy and Wippa on radio network Nova, and Chrissie Swan host of Ten’s Can of Worms and a radio show for Mix FM.

Before the selected housemates were sent into the house, a rehearsal period saw two groups of 14 people enter the house to allow producers to test out its workings. Camera crews were put through their paces and changes were made to the furniture.

And then it was show time.

“It’s the kind of show that once you set it on the tracks it just rolls along. We don’t have to manufacture anything. We just keep it on track,” says Nine’s Dewey.

A big production

Each week of production, BB churns out around nine hours of content. There is a rotating crew of 300. It is a 24-hour operation and the first shift starts in the edit suites around 3am.

While Big Brother is always watching, he is not always recording, it turns out, perhaps understandable given there are 42 cameras to choose from including seven traditional TV cameras, 10 fixed cameras, 19 remote controlled cameras and three ball shaped ‘hot head’ cameras that have 360 degree vision. There are also some domestic grade handicams thrown in to cover areas where footage is rarely used – specifically in the toilets where housemates have been known to hide out when they are upset, reality TV gold. The epicentre of the show is the control room. It is from here that the directors control action in the house and movement of the cameras. There are two sound booths as well as a room that houses one of the four voiceover artists who play the role of Big Brother. In front of two rows of desks, numerous plasma screens show the live feeds from all of the cameras in the house but only two streams of content are recorded at any one time.

Series director Mark Adamson explains: “We have two streams. That enables us to cover two different things at once. So if there’s a conversation in the lounge and a conversation in the backyard, the conversation in the backyard would be on stream A and the conversation in the lounge would be on stream B. And each of those streams has two outputs – a main output which is the director’s cut and the secondary output that provides the wide shot of the scene so when they’re in the edit, they can go to the wide to compress time.”

This is Big Brother’s first tapeless year as footage is saved to hard drives and backed up, a process overseen by Cutting Edge. The volume of data is already well into petabytes and Cutting Edge provides a database system that allows producers to search footage called Content Management Suite or CMS. It is used first and foremost in the control room where two story assistants, also referred to as loggers, are flat out typing up every second of dialogue recorded on the two streams.

Ben Steendyk from Cutting Edge explains: “CMS captures a low resolution copy of the footage so that the producers can access it through something like a Google search. They can put in search criteria – a day number, a housemate number, the diary room, an emotion – the loggers have captured. They can go through and find that from anytime in the series and do almost like an offline edit within the CMS system.”

An executive story assistant provides EP Blackburn with a rundown of the most interesting scenes from the house that day and he uses this to start the edit of the daily show. While Blackburn compares the editing process to news and current affairs production, he says BB has similarities to film. “It’s like a cross between a film set and a TV show. It is a film set, basically, without a script.”

The BB family

Blackburn, like many other members of the crew, is a BB veteran having worked on previous series. He says it is the number one place for crew training, a point reinforced by director Adamson. “I started at BTQ7 in Brisbane 30 years ago and it was the best training you could have because you got an opportunity to do every sort of discipline within TV. Nowadays you don’t. They start as a camera crew and they stay as a camera crew.”

Executive producer Alex Mavroidakis first worked on BB in series two as a control room producer, Blackburn worked on the first, second, third, seventh and eighth series and network executive Parker believes only he and voiceover man Mike Goldman have worked on every series. And while many crew members have returned to the show, others have gone on to utilise their BB training on other programs both here and abroad. This is a large part of why state funding body Screen Queensland supports the production. This year they chipped in $200,000.

Unlike previous incarnations, this year, viewers are being served up more politically correct content as add-ons from previous years such as the Big Brother Uncut show – known as Adults Only in 2006 – and online live feeds from the house have been omitted. Production executive Parker says this has been a conscious decision as the producers and Nine work to preserve the PG rating.

“Nine in particular wanted a family show,” he says. Mavroidakis is the first to admit that the final series of the show on Ten had to resort to stunts to up the stakes for an audience that had seen it all in the earlier series but he feels going back to the original format is what viewers needed. He says: “If you feed an audience too much sugar they need more and more so the more sugar bombs you throw in, the more audiences are going to expect. Big Brother is at its best when it’s a soap opera and the best scenes are always things the housemates come up with.”

Ratings pleaser

With the show hovering around the million viewer mark each of the six nights it is on air, both Nine and Southern Star are extremely happy. Reviving the format was a risky move given the current state of the television landscape and particularly Nine’s reputation for being gun-shy, ripping shows from the air when they fail to fire. The thought of what would happen to BB if audiences didn’t embrace the series did cross some crew member’s minds. But when asked if there was a back-up plan, Nine’s Dewey says no. “Not that I’ve been worrying myself about. You have to go into these things with a positive attitude. I know it seems like we’ve just put a whole group of people in a house but every decision was made with great care. We knew that if you built the platform correctly, it couldn’t fail really,” she says. The feeling on set is jovial. “The vibe now is like what it was in 2003/2004 in the glory days of Big Brother and that’s what’s pleasing about it,” says Mavroidakis. And what would please him even more is for the renewed enthusiasm to continue and lead to another series. With Nine due to announce their programming slate for 2013 in November, we won’t have to wait long to find out.

The ratings were basically fine but what a boring, odd ‘family friendly’ and somewhat posed series the whole thing appeared to be. I have to disagree about this series harking back to the glory days though. The series was best under executive producer Peter Abbott (who may have had a better budget also). Throughout the current series fans continually called for Friday night games and more meat to the bones of the show. There were other various issues of regional areas not seeing shows at certain times and, frankly, voting seemed problematic all the way through. You are supposed to receive one sms reply for example in any given voting period but many fans raised non-reception of this reply text on the BB FB page and so many didn’t seem to know if their votes were being received or not. Another issue for social media were overseas people initially posting torrent sites for BB and working to encourage fans away from the actual BB website itself. Those people became quite a nuisance and moderation somewhat hit and miss. All in all, this series probably did far better than some initial signs showed but it has a way to go before it can claim to be the ‘best’ BB series shown in Australia.

User ID not verified.

Best BB since series 1, although budget may not have been as high the pychlogical games played were best by far. Well done SSE.

User ID not verified.

Yes, well done SSE for making shallow, idiotic, boring voyeurism popular again. We all await a new generation of self absorbed talentless Jersey Shore style ‘celebrities’ filling up our airwaves with their inane drivel.

User ID not verified.

I couldn’t agree with Jon more.

Is this really the standard that we aspire to? With this budget, crew and equipment almost anything could be achieved and yet we resort to producing content that literally makes people stupid and perpetuates a false ideology for its already impressionable followers.

I am also calling for a ban on advertising this crap, much the same as cigarettes in my mind and if I develop brain cancer due to accidental exposure I will be the first to begin a frivolous law suit.

User ID not verified.

Wow Davin, all have a right to an opinion but comparing BB to a carcinogen seems a little strong. While I can see why some people may see the program as a tad low brow I don’t think it’s the end of civilization as we know it.

Mixed in with the inane and stupid was some pretty interesting insights. Hardly Harvard thesis quality but all the same the phycological games the producers played made it a consumer-able guilty pleasure for me. I’d like to add, I think the fact the winner was a gay man goes to show how far we’ve come, even better if his proposal helps change a discriminatory law.

User ID not verified.

Great – loved the mind games! Much more enjoyable you could explore that more.

User ID not verified.

I like Big Brother. Liked most of the series. Saw the early ones with my kids who learnt about how people act – how they love, lie, deny, betray, procrastinate, steal food, cooperate or not – and they learned all this without having to spend years at an Agency!!!

I suspect those who eschew the show are attempting to tell us something of how they perceive themselves. A sort of snobby upmarket thing. I don’t see them ripping copies of People or Zoo Weekly off shelves or protesting about chewing gum. Or going on about copies of Barbara Cartland novels in their local library.

Low-brow is all about the democratisation of art, giving the “little people” some entertainment, allowing silly shows to be watched without the cerebral rationalisation so beloved by those of little brain.

Drivel? Sure, but don’t say “no deal” because the show THAT catchphrase comes from is also drivel. Part of so much drivel on TV, food slicers, steam cleaners, exercise equipment which conveniently folds to go under the bed (forever?).

I’d invite serious discussion here, since I believe that by becoming a professional, one must give up the silly criticism of the consumer.

Gangnam style. Enjoy it, it’s ephemeral.

(big words above courtesy of private school education)

User ID not verified.

Great artiсle.

User ID not verified.