Did a short research paper just unlock Facebook’s psychometric blackbox?

Rumours of Facebook’s psychometric targeting abilities have been swirling for years. Freelance strategist Antony Giorgione considers if a little-known research paper has finally unlocked the blackbox.

How deep is the ocean?

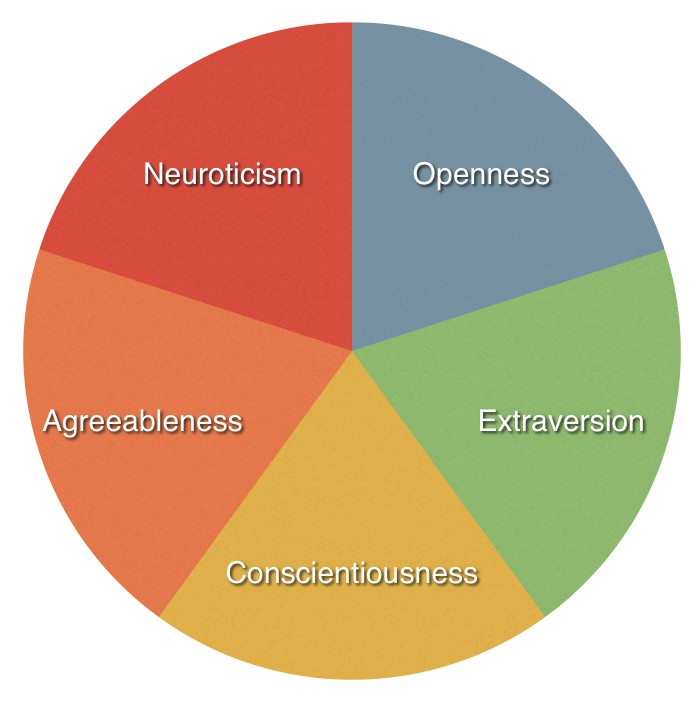

In the 1990s, psychometric profiling took a great leap forward with the refinement of the Five-Factor Model of Personality (FFM). The model consists of a number of dimensions, or traits: openness-to-experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. Each of these traits deal with aspects of personality that are largely mutually exclusive, but together form a fairly complete model.

Every individual is said to have a measure of each of these traits. If you’ve ever worked for a large business, it’s likely you’ve been subject to an evaluation along these lines.

Well researched piece Antony. And quite frightening.

Appreciated Miles

“Dr Spectre” is a name you can trust.

I should have included a photo of a white furry cat with this piece.

Interesting and thanks for sharing

Great chronology of events. Really interesting. Thanks for taking the time to publish.

Mark and Adam, thank you for your comments.

Hey Antony,

Great article, though admittedly I’m reading it quite late. Do you happen to have access to this awesome dataset? Sounds like a dream for an ML project!