Welcome to WPP, Jens: It’s going to get ugly

Controversial mergers to bed down, an exodus of key staff, structural legacy issues and allegations of discrimination and harassment. Welcome, Jens Monsees, to WPP AUNZ. He has, unsurprisingly, an almighty job on his hands, as Steve Jones reports.

When STW shareholders voted overwhelmingly to accept the takeover by WPP in April 2016 – or merger as it was billed – the positivity fairly dripped from the pages of the ASX announcement.

The takeover/ merger gave multi-national holding group WPP (or Wire and Plastic Products as it was once known) a 61.5% stake in the new Australian holding group.

STW chief executive Mike Connaghan, the newly-installed chief of WPP AUNZ as the merged entity became known, spoke effusively of combined strengths, exciting opportunities and unrivalled scale. The firm’s “outstanding talent”, meanwhile, would drive creative ideas, insights and solutions for clients.

Its combined creative agencies at the time of the merger included The White Agency, Grey, Ogilvy, Y&R and Wunderman, while on the media agency side there was Mindshare, Maxus, Ikon and Mediacom, plus public relations interests in the likes of PPR.

“WPP AUNZ will be a business unparalleled in our region,” Connaghan enthused.

The group does have scale, with its media agency holding group, Group M, boasting big-name local clients including Mondelez International (an approximate $40m annual media spend), NAB, Mars and Australia Post.

And other big-name brands such as KFC use various services across the WPP AUNZ group, with Ogilvy conducting creative, Opr doing the public relations, and Mediacom taking on media planning and buying responsibilities.

Even with the scale, synergies and spend, three and half years later, that initial post-merger optimism looks horribly misplaced. Executive commentary has become less ebullient with each passing financial report, the share price has collapsed and Connaghan, after 25 years with various local incarnations of WPP, is no longer at the helm.

WPP’s calamitous five-year share price trajectory

The group’s latest financials for the six months to June 2019 show the advertising and media investment management arm of the business (including the above agencies’ activities) brought in $236.7m, down 9.0% on the year prior. Its headline EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) was $23.5m, down 4.7%. Data investment management earned $51.0 in net sales, up 0.9%, while headline EBIT was $8.8m, up 0.1%. And public relations and public affairs had net sales of $29.0m, stable from the year prior, while headline EBIT was up 0.1% to $4.8m.

RECMA, which ranks media agencies based on their overall activity volumes placed Mediacom third in the market, behind Omnicom Media Group’s OMD, and Dentsu Aegis Network’s Carat. Mediacom’s activities were placed at $900m, a climb of 6%, while Wavemaker was down 5% to $880m. Mindshare commanded $668m, according to RECMA, and Ikon $580m.

The agency brands, however, aren’t worth what they used to be, and the recent financial results noted “weak media spend” as well as “global/ local account losses in the first half of 2019” as ongoing challenges for the once-dominant group. Not to mention the “softening of the future outlook”, “customer attrition” and “slowdown in the overall Australian economy”.

Overall, WPP AUNZ delivered a first half loss of $253m – the result of a near-$300m write down of its agency brands – while an exodus of key staff throughout the year has pointed to internal unrest.

No wonder interim chief executive John Steedman – who declined requests from Mumbrella to be interviewed for this piece – admitted to investors the results were “disappointing”. Other, more colourful descriptions of the performance, were not in short supply.

Steedman: 12 months as interim CEO

Not that the veteran adman need concern himself any longer with explaining WPP AUNZ’s woes to an unimpressed market. Today, after 12 months as caretaker CEO, Steedman will retreat to his role as executive director and chairman of media investment management.

Into his place as CEO will stride Jens Monsees.

He does so with the share price languishing at 52c – it has failed to recover from the sharp decline on Connaghan’s exit – and with a general sense of uncertainty, weariness and angst permeating WPP’s self-styled campuses.

There are mergers to bed down, mergers to come, the rising challenge of consultancies and the small matter of legal action lodged by two former executives.

The job, if it needs stating, is a big one.

Where to start?

Monsees, a German with no previous experience in the local market, has spent a majority of his career client side, most recently at BMW where he oversaw a digital overhaul. It was his knowledge of business transformation, together with his client-side and Google background, that enticed WPP.

In addition, the board spoke of a “right cultural fit”, together with Monsees’ ability to “inspire and lead the tremendous talent around him”.

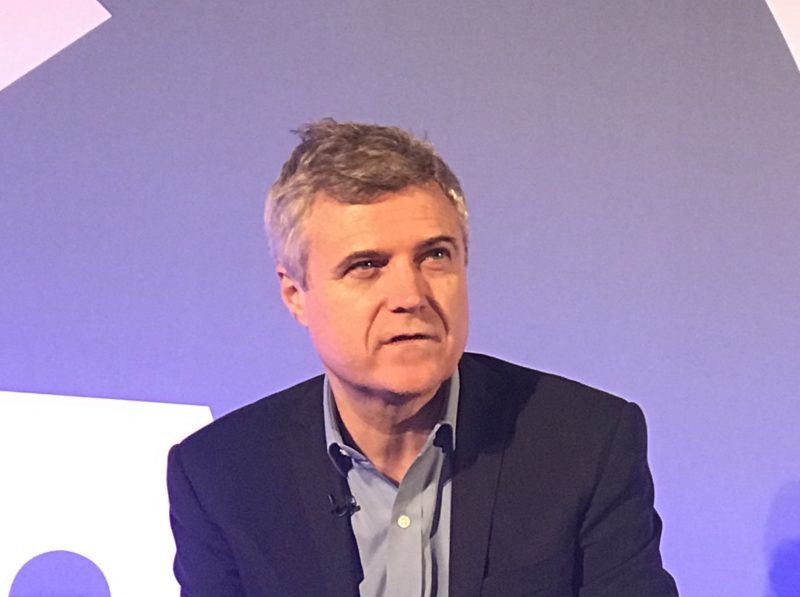

Jens Monsees: wanted by WPP for his digital transformation skills

Yet far from a cultural fit, his arrival is expected to come as an uncomfortable cultural shock to many in the business, including WPP’s executive council (Exco). And so it should, some believe.

Sources variously describe the current status quo as an “old school network”, “disconnected” and “hierarchical” with members of the Exco conflicted by their day-to-day jobs and their wider role of looking after “clusters”, which includes agencies competing with their own.

“The Exco basically runs WPP, or govern it, with too much conflict of interests between those on the council and the agencies that report into them,” one agency executive claims. “It existed at STW before the merger. The structure was wrong and many agencies felt it. Jens Monsees needs to fix that and bring people down from their ivory tower.”

Decisions are also said to have been made “with little context to what really happens” within a particular agency, while old-school thinking was still prevalent.

“Some are extremely traditional leaders who only understand old school advertising. You’ve had Steady [John Steedman] running it for the past 12 months. Tremendous guy, who everyone has utmost respect for, but he’s no spring chicken.”

The Exco was born from the labours of a strategic review of STW in 2015, spearheaded by Connaghan after a dismal 2014. He had branded the win/loss ratio of some media and advertising agencies – which included Ikon, Moon (swallowed by Ikon in mid-2015) and Ogilvy&Mather – as “completely unacceptable”.

Meanwhile, chairman Robert Mactier, another STW stalwart who took the same role in the merged WPP AUNZ enterprise, described 2014 as the “type of year no chairman wants to have”.

STW, and then WPP chairman, Robert Mactier

The annual report that year also contained one of the first mentions of “horizontality”, founder Martin Sorrell’s clumsily-worded global WPP strategy which Connaghan translated as growing “deeper, more influential relationships with clients”.

It is understood Connaghan enjoyed a harmonious relationship with Sorrell, but did not see eye to eye with new management or share the vision. “He found it difficult once Sorrell left. I think he’d had enough of them, and they’d had enough of him,” one WPP source says.

Insiders believe the Exco was made up of close associates, supporters and friends of Connaghan, some of whom, it is thought, will be nervously awaiting the arrival of Monsees.

It is acknowledged that the Exco reporting structure has created tensions, in some divisions more than others.

Not that Connaghan was unduly concerned, according to sources close to the former CEO. “Some people couldn’t handle it but he wasn’t worried,” one tells Mumbrella. “His view was they were paid a lot of money so get on with it. There was some good people in there.”

Yet it would come as little surprise to others if Monsees had been briefed to break up what has been branded an “old boys and girls club”.

“That is part of the reason they searched internationally. They wanted someone who had no allegiances,” one says.

Another voiced “shock and amusement” at the appointment; shock because of Monsees’ lack of local knowledge, and amusement at his exorbitant salary, which could run into several million dollars each year.

“But then it made sense. If you hire locally there is every chance they will get caught up in the baggage and heritage and relationships to do what needs to be done. Recruiting from outside will bring someone with a dispassionate view and fresh perspective.

“Jens is not from our world, and won’t be bound by the traditions of our world. He’s used to asking for stuff, and getting it, and that is the mentality he’ll bring to the business in Australia. It will be a shock. He’ll recognise some who are up for it and others who won’t be.”

One ex-WPP stalwart who speaks with Mumbrella suggests morale has been poor, fuelled by trepidation over the immediate future. There is also unease, and a degree of mistrust, that Monsees is unfamiliar with WPP’s Australian operation, has barely worked outside Germany and “never been on our [agency] side”.

Not that he will lose any sleep over suggestions, or internal suspicions, that he is the wrong man for the job.

“For good or bad, he has no affiliation with the agencies and none of the people. He’s not there to build relationships or build a company. He’s there to smash it up.

“Jens has done a huge tech transformation inside BMW. WPP needs that expertise. They need to get a balance. They have tech companies and traditional agencies but have never been able to pull it together. Jens could be the man to do that.”

Across the business more widely, sources believe WPP has failed to invest in new talent, or simply overlooked it. Senior positions and promotions have been won by “good company people” who are loyal, “do as they’re told” and do not ruffle feathers.

“There is a principal that you rise to the level of your own incompetence, and that is maybe what happened within WPP,” one senior industry source with close links to WPP observes. “People get promoted into jobs that are ultimately too big for them. That might be true for a number of people within the organisation but some of those changes have now been made.

“But there is talent there, or at least there was. It’s just not been supported as much as it should. Hopefully Jens will recognise that.”

Despite the apparent internal reservations, one shareholder speaks of “excitement” at what Monsees could potentially do, reiterating the benefits of hiring an “outsider”.

Among the first tasks, the shareholder says, should be to draw a line – well overdue – under the lingering tension that is said to still exist between STW and WPP. An atmosphere of “them and us” had been allowed to fester, with STW management said to have “conveniently forgotten” its own operation had been a horror show in the 18 months prior to the deal with Martin Sorrell in 2016.

STW agencies included The White Agency, Ikon and The Brand Agency.

STW Group had been under-performing in the 18 months prior to the WPP deal

“I thought there was enormous potential, through scale if nothing else, but most people would agree that WPP has not made the most of the opportunity. But STW had been performing very poorly which was forgotten and pushed under the carpet by previous STW management. There was always an issue of them and us. One thing Jens needs to do is break those territorial instincts.”

Monsees, while only officially taking charge this week, has spent the last four months familiarising himself with the business, a period which included a week-long trip to Australia shortly after accepting the role. During the reconnaissance mission, agency bosses and executive leaders are understood to have presented to the incoming CEO, some of who were, in effect, said to be presenting to keep their jobs, and possibly even their agencies.

“He got a feel for the business, he knows the balance sheet. He knows the ones that are performing and the ones that aren’t and has an opinion of what is going well and who needs to go,” one source familiar with events tells Mumbrella. “He won’t need to wait 60 days before taking decisions.

“Furthermore, WPP took 12 months to get someone in place so they’ve largely been treading water for a year. Jens, and WPP, can’t mess around. I feel he’ll come in and there’ll be carnage pretty quickly.

“It’s going to get ugly. It won’t be a good Christmas for some people.”

Mergers past, mergers present and mergers yet to come

That “carnage” is certain to involve the further consolidation, closure and sale of brands. Part of WPP’s global strategy, even before the acrimonious departure of Martin Sorrell in April 2018, has been to cull the number of agencies, a move designed to eradicate duplication, cut costs and make life simpler for marketers bamboozled by the number of agency “touch points”.

Such rationalisation is the antithesis of previous strategies pursued by STW in Asia Pacific and WPP globally, where any agency that moved and claimed digital expertise was an acquisition target. In 2013 Mumbrella reported that STW had been in talks with no fewer than 150 companies in Southeast Asia, as it, and WPP, sought to amass agencies in every conceivable channel and discipline craved by modern-day marketers.

WPP and STW brands at the time of the merger

“Holding companies wanted to own every part of the purchase cycle. They obviously wanted media, but also a shopper agency, production agency, sales promotion, events, social agency and the rest,” one analyst says. “There was this master plan that if you had all this expertise and did everything along the cycle, clients would take the whole lot from the same holding group. You could argue it sort of made sense. But not now. Now it’s all about simplification.”

According to another commentator, the spending spree began with Singleton Group – owner of John Singleton Advertising – before it rebranded to STW in 2002, shortly after acquiring 49% of J Walter Thompson from WPP.

“The market has always struggled to value listed advertising and marketing businesses, so acquisition was the only clear way they could demonstrate growth,” he says. “But it grew to something like 80 companies and, as we all know, became too unwieldy. It was a rag bag of businesses with no apparent overall structure or strategy.”

“WPP is an engineered business, not an organic business. Today, it’s about being fleet of foot, imagination and a bit of daring. They have tried to engineer nimbleness by acquiring smaller agencies, but those agencies always become stifled by the requirements of being part of a holding company. The heyday of a smaller agency is never after they have been acquired. It’s when they were in growth and independent.”

One prominent industry strategist adds: “Everyone thought the big prize was having the biggest networks to get the biggest clients. There was a huge incentive to get there. But that also meant a lot of debt. If these businesses had not taken on debt, they would not then need to maintain ridiculous profit margins in order to pay them off. That is half the problem. Because you have this shed load of debt, because you made all these acquisitions, suddenly you don’t have any room to move.”

But having been instrumental in so many of the acquisitions, critics of Connaghan say he was too slow and too reluctant to make enough “tough decisions” to consolidate. Monsees will have no such sentimentality or attachment.

“Mike has personally nurtured some of those local brands and he was expected to kill the ugly ones,” one says. “He couldn’t do it. Jens will.”

But others warned that continuing to eliminate local brands – PPR, a profitable PR business was the latest to disappear – would be a grave error for Monsees.

“The fundamental thing that people fail to understand in this market – and it’s something Martin Sorrell inherently knew – is that it’s a local market,” one former executive argued. “The vast majority of revenue is local, so all the banks, government, retail is incredibly important. Pursuing a strategy where you are getting rid of the local businesses and relying on global banners is fatal.

“Rationalising brands can be fine, but one hell of a lot of value can be destroyed for organisation simplicity. It may make life easier, but that doesn’t mean better. ”

The source adds: “Jens is walking into a great business but it is structurally, and now strategically, challenged.”

Furthermore, it is also claimed that a handful of local STW brands – Aleph, The Brand Agency and Ikon among them – account for more than half of the group’s profits.

The Brand Agency: one of five local agencies said to have delivered half the group’s profits

The drive to streamline the WPP structure has seen a raft of mergers in recent years, the most recent last month with local outfit PPR folded into BCW, itself created through a merger of Burson-Marsteller and Cohn & Wolfe in early 2018.

Further back, in early 2017, STW digital agency DT rebadged as AKQA, marking the WPP agency’s entry into Australia. AKQA has since swallowed digital marketing and media consultancy, Switched On.

In the same year, The White Agency merged with Grey Group Australia to create WhiteGrey, while in the spring of 2018 came arguably the most contentious of the mergers, with Y&R and VML combining to form VMLY&R, and JWT and Wunderman morphing into Wunderman Thompson.

On the media front, Maxus and MEC merged two years ago to create Wavemaker, to operate alongside Mediacom, Mindshare and Essence in the GroupM stable.

Other, smaller mergers are likely, with some already underway, at least as far as back office functions are concerned. In one example cited to Mumbrella, event agency Play Communication has effectively been folded into Maverick, although the Play brand remains as both agencies have automotive clients.

“There has been some under-the-radar mergers, pulling things together but keeping the names to avoid conflict.”

Predictably, perhaps, Monsees will be faced with particular challenges within VMLY&R and Wunderman Thompson, with both operations experiencing an exodus of key personnel in recent months, including the joint managing directors of VMLY&R, Aden Hepburn and Pete Bosilkovski, and Wunderman Thompson MD Paul Everson.

One industry expert says the current strategy to create new agencies by merging existing ones has historically been flawed.

“I don’t think in the history of M&A’s anyone has ever successfully reconfigured a set of assets,” he says. “Why would you merge Wunderman, a pretty good direct response company, with JWT, a dying ad agency? It sounds like you’re trying to kill an asset, not grow one.”

He adds: “There are two ways to look at rationalisation. One is putting a good agency with a bad asset in the hope of turning the bad asset into a good one. That is what they are trying to do. But no one has ever been able to show me an example where that has worked well.

“The alternative is to smash two bad assets together and try to rationalise their costs and punch out redundancies. I’d have merged JWT with Grey to contain the shit, keep those dying business that have declining revenue and maintain high margins. Who cares if revenues are declining as long as you are profitable? I believe that is what Martin Sorrell would have done.”

The demise of JWT and Y&R as standalone agencies was viewed as cultural vandalism by some, and a necessary evolution by others – or quite possibly a combination of the two.

In the case of Y&R, the agency had its heart “ripped out” when the Department of Defence moved to Havas Worldwide in 2013 in what sources claim was a “procurement-related loss”. The agency had “great talent and consistently solved the client’s problem” but was “undone by an inferior solution at a low price”. The merged entity has since re-won the account.

Being so reliant on one client, however, can be viewed as reckless, with questions raised over its failure to win new business.

Of JWT, the consensus is one of a once-great global advertising agency that had been “stuck in the mud for years” and, in a familiar story, failed to react fast enough to a changing landscape.

“It just had not evolved its offering,” one former close colleague of Martin Sorrell explains to Mumbrella. “It was still a Madison Avenue advertising agency which spent too much time telling clients the new world of advertising was tosh and less time reacting.

“Martin has not been shy about telling anyone who’ll listen that WPP has not been nimble enough and that his new business represents everything that clients look for. He conveniently forgets he was in charge of WPP for a significant time when it failed to be nimble and make those decisions.”

Both mergers have been described as “clunky” with a clash of cultures partly responsible for the staff exodus. But sources with knowledge of the VMLY&R merger offers a different view, arguing the merger has produced a “powerful combination”, even if Y&R has been “dying fast” as a standalone creative agency.

However, it is understood senior executives were becoming frustrated at losing autonomy, and the impact that would start to have on the quality of work and client relationships.

As far as media goes, GroupM in particular was hit by the loss of several global accounts in 2018, Ford among them, with the agencies also said to have lost their “swagger” in recent times, with key departures once again among the cited reasons.

One WPP rival admits there had once been an assumption that GroupM agencies would “win everything” such was their “assertiveness” in the market.

“Not so now,” the agency boss says. “It’s a tough media environment, but they seem to have lost their way more than most. They used to be a powerhouse, but it’s a different beast now.”

While some believe the reporting scandal which engulfed Mediacom in 2014 is long forgotten, others suspect that may not be the case.

More widely, value banks have become “dirty words”, and transparency – while clearly imperative – has taken its toll with rebates and other trading benefits allegedly a thing of the past.

“Procurement is looking over you, loopholes have been closed and it’s a much tougher business environment,” one former GroupM executive says. “There aren’t the margins you used to get.”

In such an environment, questions have predictably emerged over the sustainability of operating four media agency brands. In its half-year results, the advertising and media investment management division saw earnings tumble almost 17% to $23.5m, net sales down 3.6% to $237m and margin falling to 9.9%.

“Locally and globally some hard choices need to be made. Do you they really need four big media agencies? Could there be three, or even two?” one WPP source asks. “It would be interesting to put one of them into Wunderman Thompson or VMLY&R. Maybe that’s the way you deal with it. Consolidate them with another agency and provide a cradle to grave solution. I think we will see a return to full-service agencies which we are already seeing through the merger of traditional and digital agencies.”

Agency collaboration and “horizontality”

Among the contentious issues facing Monsees will be the ‘horizontality’ strategy. While the word itself was internally unpopular and is no longer part of WPP vernacular, the strategy of custom-built teams for clients – a full-service agency by any other name – appears to be intact.

Nevertheless, it is clear that pulling staff from agencies to create bespoke business units for individual clients – including Team Red for Vodafone, which recently retained the account – has created tension within WPP. Not least of the issues is a structure where each agency is judged on its P&L, and therefore reluctant to share or lose staff to other business units.

Furthermore, staff themselves were sometimes unhappy at being asked to work on one specific client.

Team Red was set up to consolidate WPP’s Vodafone accounts under one dedicated agency

“Do you want to work on the Vodafone account for the rest of your life? Probably not,” one creative says.

Resistance to the team model was said to be common, and stemmed from uncertainty about where revenue would sit. “If agency heads live or die by revenue and margin, you can’t blame them,” says one source.

“That said, generally, it works well. It’s still a work in progress locally, but we felt its successful implementation could be the key to the region. It requires a particular style of working and collaboration between agencies and they instinctively want to compete with each other. Sorrell just knocked heads together and hopefully Jens will do the same here because they probably have not got that right yet.”

Martin Sorrell

Connaghan is understood to have acknowledged that tension existed, but was adamant it was the correct approach. Furthermore, blaming horizontality was an excuse for agencies which were “failing to evolve”.

“At STW it was all about ‘Better together’, about being part of something bigger. Mike’s view was what was the point of having a group if you can’t cross-pollinate and help each other? That was what is was meant to be about,” one observer says.

Yet the financial structure appeared to fly in the face of such a collaborative approach, others argue. While Connaghan presented an atmosphere of collaboration, agencies were more interested – and concerned – about their own bottom line.

One former WPP agency head reveals the company had “very clear and strict metrics” which stymied any long-term thinking or planning.

“All the agencies had a number to hit and what disappointed me was that while we did try to push collaboration there was not much incentive to do so,” the former CEO says. “Particularly when times are tough, you are going to focus on your own business and no one else’s.”

Those who particularly struggled were the WPP agencies which, after the merger with STW, suddenly found themselves under intense scrutiny as part of a listed business.

Such scrutiny will be among the “toughest challenges” for Monsees. Kenya is the only other separately listed entity in the WPP empire.

“With that comes a level of focus and scrutiny that hardly any other regions have,” he says. “Everywhere else rolls up to WPP globally. In Australia and New Zealand, the market is analysing the performance and that sets a different mindset. On one hand it sort of gives you focus but on the other it changes your mentality and became a month by month, quarter by quarter proposition.”

In the years before the STW deal, WPP agencies operating locally adopted a longer-term view without the immediate pressure of delivering profits and hitting targets.

Another former WPP agency boss echoed the sentiments, insisting the overriding focus among some members of the executive council was hitting a number, with little regard for longer-term thinking and brand building.

The challenges of creativity, consultancies and CMO short-termism

However irritating Martin Sorrell’s jibes towards his former company may have been about his “nimble” operation, S4 Capital, there is widespread agreement that legacy companies have been slow to adapt – as the former WPP boss stressed again recently.

Writing in the WPP annual report earlier this year, global CEO Mark Read – Sorrell’s successor – agreed than it could ill afford “to be nostalgic about our agency brands”.

Mark Read: WPP is a ‘creative transformation company’

And no one could accuse him of failing to match his words with action. The sacrifice of both JWT and Y&R – with 251 years of history between them – is testament to that.

Read wrote: “Agencies perceived to be lacking in contemporary skills in areas such as data, technology, experience and commerce have come under significant pressure.”

He added that WPP has become “too unwieldy, with too much duplication” which as a result “has not always been as focused or as fleet of foot as it needs to be”.

Read has also acknowledged the need to invest in creativity, something veteran marketer Keith Weed – now on the WPP board – has urged the company to do.

Connaghan, who did not respond to requests for comment from Mumbrella, was understood to be relatively satisfied with the creative output locally, but was also aware there was room for improvement.

That said, one creative points to Greg Creed, CEO of Yum Brands, who recently described Ogilvy’s local work for KFC as among the best in the world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CQQ4flIGuw

Read’s assessment that agencies which lack modern disciplines are under pressure is hardly a ground-breaking realisation – but aside from the realities of data, digital and technology platforms, marketers themselves have changed, their heads turned by the latest trend or buzz word.

One former WPP executive, now running a new company, says: “The Facebooks and Googles have romanticised working with start-ups and eroded the value of big brands. If JWT and Y&R were such great institutions why were they not picking up shit loads of new business? The culture has changed, it’s cool to experiment and be different. Everyone wants to work with sexy new things.”

Jason Rose, associate director of Concept Financial Services Group, an investment bank, says the CMOs and CEOs of 2019 are also generally risk-averse which plays into the hands of consultancies which are muscling in on traditional agency stomping grounds.

“Ultimately it’s a battle for the ear of the CMO and CEO. Who they are going to listen to when it comes to prioritising spend?,” Rose says. “The consultancies are more savvy and experienced at having those high-level conversations. They can distil those conversations into language that appeals to the risk averse, bean-counter nature of the CEO, CFO and CMOs. That is the competitive advantage of consultancies.”

Jason Rose: Marketers are risk-averse

Furthermore, Rose argues that in today’s society, the creative advantage held by legacy firms has dwindled amid a creeping fear of their brand causing offence.

“I see CEOs who are not particularly comfortable with creativity as they see it as something potentially risky, particularly as we are becoming more risk averse as a culture. If you say something left or right of mainstream opinion today, you run the risk of being obliterated on social media.

“They are far more comfortable spending money on technology platforms. That is what they are gravitating towards.”

The well-documented short tenure of CMOs is also a problem, with marketers more concerned about quick results than long-term brand building.

Decisions are being made on easily measurable metrics, some believe, which one veteran adman blames for the “head-long rush into digital media”.

“It’s easy to throw up a chart saying we have two million followers on Instagram. Back in the day there were metrics about sales and share and profit.”

The failure of some brands, however, can be traced to a failure to articulate what value or ideas the agency could offer, and how it would “make the CMO famous”, another suggests.

Instead, there has been a tendency to compete on what capabilities the agency has.

“We forgot about the overall purpose of an advertising agency when specialist agencies exploded, we started competing on capability. Do you have digital? Do you have direct marketing? Experiential? They were all competing for the client’s budget and took their eye off the fact that their real purpose was to drive growth and performance for the client.”

Court cases

Aside from the many structural and market challenges that he will need to navigate and address, Monsees is faced with two desperately unwanted distractions: legal battles involving former executives.

The first, which came to light at the end of July, involves former Mediacom Melbourne general manager Rob Moore who claims he was made redundant after disclosing his battle with depression to CEO Willie Pang.

Rob Moore

Two weeks later it emerged, Carmel Williamson, the former managing director of Team Red, had earlier made allegations of harassment amid a “boys club” culture that ultimately led to her being dismissed after just six months. She also claims the situation left her in need of psychological treatment.

Carmel Williamson: claims of boys club

WPP has rejected, and will contest, the allegations.

“Whatever the truth of those matters, they should never have got this far,” one source says. “It is symptomatic of a company without a leader. That’s not meant as a reflection on John Steedman, he’s a great guy. But he’s the interim CEO and issues like this, which should be nipped in the bud and dealt with, can fester when a company is waiting so long for a new CEO.”

Others point to Williamson’s Team Red legal fight as an example of the in-fighting that can characterise the custom-built client teams.

Market expectations

With much landing on Monsees’ desk, no one is expecting the share price to recover overnight from current levels. There are some who believe the valuation is artificially low and paints a false picture of the company’s health.

Take away the write down in the August interim results – one well-placed executive described the write down as “all bollocks” and “meaningless paper crap” which is “ancient history” – the headline earnings were $43m, down almost 13% but still “not that bad”.

For Rose, from Concept Financial Services Group, Monsees needs to excite the market and offer up a vision, something he says has been lacking.

“I read the quarterly strategy updates and for a communications business there is not a lot of inspiring material,” Rose says. “In fairness it has been a tough market, but I have not seen much leadership that gives you confidence that they’ll be doing anything particularly interesting.

“They need to have someone who can create and sell the vision. From an investor’s perspective you think ‘Where are you going to be in five years?’ and I don’t think many people will be convinced that they’re about to embark on an impressive growth trajectory. I just don’t see where the big upside is going to come from.

“He needs to articulate what they’re about, and convince people to come on board. That is what people will be looking for.”

Jens Monsees comes with a high price tag. For his efforts, he will be paid a $1.5m signing on bonus and up to $5.5m per year.

The WPP board will be praying he is worth it.

Great piece but the RECMA numbers are a nonsense. They bear no resemblance to what’s really booked.

Take Groupm losses over the last three years. Unilever, P&G, Jeep, Aldi, CUB, Carnival, most of SA Govt, AMEX, Nestle, GSK, VW, Pizza Hut, Specsavers and VW to name just a few !

That’s a massive amount of billings and a pretty bad story in client wins over the same period.

Tellingly the vast majority of losses are local clients .

Melbourne groupm is a disaster zone and the exodus of key staff Over the past 12 months shows how deep the issues are there.

Without groupm firing WPP has no chance to get back to where they, and the investors need them to be.

Be a few very nervous people at Berry St this week.

You can add VIC Govt to that list.

Supposedly out the door after too many warnings . Other agencies already being briefed.

I’d say Mindshare and their local exec have done well the past few years. The leadership at groupm and its other agencies not so much.

Anonymous comments like Herman’s are part of the problem in our industry

Says most losses are local clients but then lists 11 of 13 brands which are global (!)

Even the list is wrong , they have maintained most of SA Gov’t not lost it. (Where does he get his info?)

Recma numbers are all bulls**t though, i’m surprised anyone pays any attention to them

And Melbourne is a bit of a disaster all round for GroupM – Mediacom Mindshare and Essence all losing staff and clients. Only exception perhaps is Wavemaker with Aus Post win

Yes they’re mainly global brands but the vast majority were local decisions to move . AMEX and VW were global decisions .

Whichever way you cut it it’s a terrible result compared to OMG and IPG over the same period for example .

It is natural to be nostalgic for the salad days when an ad “pulled its head off!”

That’s 1980s industry speak for an advertisement that got the customers to keenly and quickly buy the product*.

So the agency senior-execs could then go to lunch and not return. Seeking nirvana in manifesting French World War One Marshall Petain’s philosophy of “all that matters in life is food and sex”.

*Source: Retired ad guru Tim from Toorak (who knows who he is).

Biggest hospital pass ever … sinking ship

I’d suggest a few high profile local execs at Groupm & WPP spend less time humble bragging on LinkedIn and actually deliver something tangible.

But.. but.. their personal brands are so important to their employers..!

Whoever said that comment around internal M&A is on the money. When have these big internal mergers ever worked?

What a great article.

This is an all-or-nothing move and the only option left. A leader like Jens will either revive them or kill them faster. They are on a path to death so there’s little to lose.

WPP is totally cooked. Next…..

I can not understand why clients like Westpac and NAB are still onboard. Why do they stay if the ship is sinking?

https://mumbrella.com.au/mindshare-expands-remit-on-nab-account-to-include-search-and-social-596937

“Mindshare has proven to be a great partner, and we are pleased to extend our partnership. Our account team at Mindshare is responsive, engaging and genuinely interested in NAB and continuing to improve our customer experience.”

Bet Steady is loving these!

Wow did not realise that STW was struggling at the time of the merger, I always thought they were the stronger of the two companies.

Now it makes zero sense that the entire Exco is ex STW and if you came from a WPP company you were made to feel inferior.

A huge same to see so many people treated badly just because the don’t fit in the “boys club”.

Yeah, never quite got why power was given to the blunter instruments. Perhaps Martin felt indebted to them for so successfully driving down the price tag of his new acquisition.

On my analysis the average board tenure at wpp is now significantly longer than that of renewed wpp plc board. Mactier,Anderson and the host of old others should have been removed by plc and a new board pick the next ceo of wppaunz.

Didn’t happen. So this old team left a legacy behind in Monsees.

So. How will he do?. Well when was the last time the Germans made a movie comedy that travelled internationally? . Never.

And my dad was German and mum Austrian. And the fun, when I was young, was in paucity as per German upbringing All you guys were lucky. This is not going to work at wppaunz.

Don’t forget [Edited under Mumbrella’s comment moderation policy]

Well an agency has to fight on creativity. Entertainment and appealing messages..

I don’t see [Edited under Mumbrella’s comment moderation policy]

A group ripe for downsizing. Much different market now than WPP salad days , Group M not relevant any more so that’s where I would start

If you’re leaving uni or under 28 you’ve got little interest in working for an advertising agency. Product teams at startups or tech firms are where the real talent is headed and where the money is.

If you’re client side, young or have a customer background wanting a CMO-type responsibility, you won’t be going to ad agencies to boost your business, career and profile. Indy and specialist shops, or even the consultancy-aligned agencies will keep the wider C-suite happy.

WPP is for career retirees

you know what they say about opinions…

Any evidence to back that up, or are you just talking for yourself?

Talking to a lot of recent/soon to be grads with STEM backgrounds I would say Jurassic Park is right.

because people with STEM backgrounds have always made up such a huge proportion of an agency’s graduate intake…

…and that’s the real issue and why they are all struggling. You can’t help clients with their problems if you don’t have skills in technology, data, or advanced analytics. Give me a creative thinker who understands numbers over a creative one who doesn’t any day.

If you want to be in the game of business transformation, you need to have STEM backgrounds.

TV ads =/= linear growth anymore

In respect to ‘WPP being for career retirees’, the evidence you seek is the Linkedin profiles of the Exco. Same network for a decade or more, rotating through roles & offices.

A key issue with being the largest holding company in the market is that you invariably become complicit in driving down your own (very thin) margins. Y&R pitching against Grey or Ogilvy and Group M trying to carve off low value creative for themselves.

I know of no other company that would prioritize and incentivize such destructive internal competition above strategic alignment.

Sir Martin started this mess, not the local team. He also created the requirement to service an astonishing debt, acquired through the purchase of businesses where the people clearly matter more than the brands they work for.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that some of their brands are failing to manage cultural challenges when short term debt (bond) management (servicing the purchase of mostly intangible assets) is the key KPI.

Good businesses understand that people are the most important asset. In the case of WPPANZ, more were bought than bought in.

Look for the new bloke to move the business towards more profitable paddocks. But none of it matters if he can’t get the most basics of business right.

Good luck to all invested.

Blaming Martin for the mess now doesn’t wash. It’s $300M smaller than it was when he engineered the takeover of STW. And the downsizing started from Day 1 of the merged entity and that has been very well summarised in the above article. Well done.

One of the best pieces I have read on Mumbrella. Nice job Steve!

WPP AUNZ is the football club who in 2019 is looking for the coach and footy dept who won premierships in the late 90’s. Refuse to accept the game has changed and by stacking it with yesterdays heroes they ensure that culture is ingrained.

It is a pretty horrible place to work. They try to distract from the toxic cultures, below market pay, bullying, unsupportive people managers and focus on delivering a vast amount of work above any sense personal wellbeing with fancy offices and free food.

You’ll be hard pushed to speak to any ex WPPAUNZ employee with anything positive to say.

Count yourself luck you got free food…

It is a pretty horrible place to work. They try to distract from the toxic cultures, below market pay, bullying, unsupportive people managers and focus on delivering a vast amount of work above any sense personal wellbeing with fancy offices and free food.

You’ll be hard pushed to speak to any ex WPPAUNZ employee with anything positive to say.

Here here! Could not have said it any better myself. Unless you are a senior exec you get no recognition and expected to work over hours with zero entitlements.

It was ‘Sir’ Martins idea to put the incompetent team from STW in charge of the newly merged company. He left anyone with talent across AUNZ to the mercy of a large group of self interested semi retirees from STW and then a bunch of his not very bright mates. They simply rocked in and corporate bullied anyone who disagreed with them. They destroyed all faith in the business, all the talent left and then all the clients followed. Jens will need to be Jesus to make this a success, he’s not, it won’t.

If the cleanup runs as deep as this article suggests, the redundancy payments will be phenomenal. For some, Christmas will have come early.

for tanking WPPAUZ – not great Steedman.

He was great 15 years ago tho – he really showed those media networks

Great article. Coming from BMW, Jens will be expected to rapidly engineer a giant money-making machine out of a lot of complex parts. It’s a big ask for someone who doesn’t really know the businesses or the market, but bold thinking is supposed to be what this industry is about. Jens may find the biggest challenge is that too many WPP execs have been beaten into Barinas after years of what you might call savaging. With both payouts and PTSD, lots of WPP’s best people have already left.

Great read! Thanks Steve!

The best time for any CEO to start is when a business is in free-fall.

It’s really a win-win situation for Jens.

Fail and it’s not his fault.

Succeed and the credit is all his.

Year 1 = massive cost-cutting, lay-offs, mergers and trying to sweet talk clients into newly merged WPP agencies.

Clients will use this as an opportunity to squeeze WPP on costs, or leave.

Interesting times ahead.

T

I agree. If it tanks he can blame the previous management group. If it succeeds he can toot his own horn and say it’s all him.

Either way he wins (and is getting paid).

I for one cannot wait for a change or reign.

After years of watching and experiencing people being bullied, treated poorly and made ‘redundant’ for either pushing back on or not fitting into the high five-ing ‘friends of the exec-board’, and having to sit muted with fear, passed up on promotions or burning-out because saying no to endless work was not an option – even while the exec boards friends were at home sunning themselves reaping the benefits of being protected and knowing people high-up.

I cant wait to see people being held accountable for doing nothing but lunching, I cant wait to see these people corrected for bullying, fired for losing business and I cannot wait to never here ‘I know x on the board’ anymore. No more promotions or hirings because they went to ‘Scotts’ or some Double Bay private school.

Heres to 2020.

Great story Steve with extensive research and a thought provoking long read. A positive change verse short click bait headlines … with real in depth insights. Lets have more of this investigative journalism!

There is a back story. Mark Read and Jens go way back. Mark has a plan for WPPAUNZ. It’s aggressive and will be very unpleasant. To such a degree that he needs an outsider he knows/trusts, with no local emotional ties, with experience of organisational transformation and who he will pay handsomely to….yes, ‘execute’….the plan. In 2 years or less WPPAUNZ will look nothing like it does today. Good or bad it is what it is. Sorry….

….not sorry.

Intersting to see how things are going for WPP AUNZ two months down the track. Certainly, not much time yet passed to get a new company strategy going. But a new vibe must be spreading out there (at least that’s what I heard from my ex colleagues!) Hopefully, it’s all for the best as it could not get any worse… Cheers to Jens anyways and good luck.

Never read this article previously until now but so many facts in this piece. The WPP merge with STW never happened it was a STW takeover pure and simple.

Too many life rafts provided for loyal STW employees. “Talent” is defined by an employees tenure with STW rather than someone’s skills, experience and ability for the roles.

The group is extremely political – the inside joke is jobs for the boys. Too many people in head office hired by a personal relationship with no defined role, and no value being added other than the cost of their salary on the groups P&L

Will be interesting to see Jens first moves and whether the CFO will survive